Edward Condon facts for kids

Edward Uhler Condon (March 2, 1902 – March 26, 1974) was an American nuclear physicist and a key figure in the early days of quantum mechanics. He helped develop radar during World War II and briefly worked on nuclear weapons as part of the Manhattan Project.

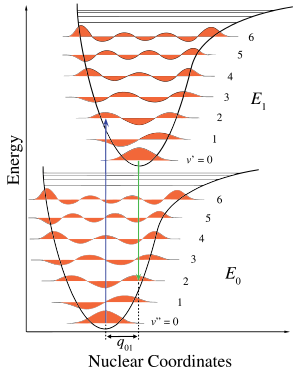

Some important scientific ideas are named after him, like the Franck–Condon principle and the Slater–Condon rules. From 1945 to 1951, he was the director of the National Bureau of Standards (now called NIST). He also led the American Physical Society in 1946 and the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1953.

During a time known as the McCarthy period, when the U.S. government was looking for people suspected of being disloyal, Edward Condon was unfairly targeted. He was accused because he was a leader in the "new" and "revolutionary" field of quantum mechanics. Condon strongly defended himself, showing his deep commitment to physics and science.

Later in 1968, Condon became well-known as the main author of the Condon Report. This was an official study, paid for by the United States Air Force, which looked into unidentified flying objects (UFOs). The report concluded that most UFO sightings could be explained by normal things. A crater on the Moon, called Condon, is named after him.

Quick facts for kids

Edward Condon

|

|

|---|---|

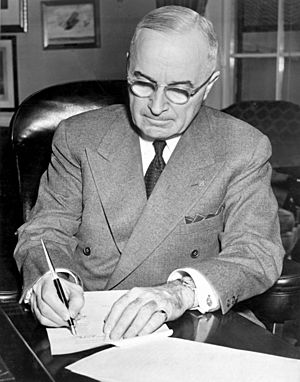

Edward Condon (undated)

|

|

| 4th Director of National Bureau of Standards (NBS) | |

| In office 1945–1951 |

|

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Lyman James Briggs |

| Succeeded by | Allen V. Astin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 2, 1902 Alamogordo, Territory of New Mexico, USA |

| Died | March 26, 1974 (aged 72) Boulder, Colorado, USA |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley |

| Known for | Condon–Shortley phase Franck–Condon principle Slater–Condon rules Nimatron Quantum tunneling theory of alpha decay Radar and nuclear weapons research Target of McCarthyism |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | On the theory of intensity distribution in band systems (1927) |

| Doctoral advisor | Raymond Thayer Birge |

| Doctoral students | Edwin McMillan |

Contents

Early Life and Education

Edward Uhler Condon was born on March 2, 1902, in Alamogordo, New Mexico. His father worked on building railroads. After finishing high school in Oakland, California, in 1918, Edward worked as a journalist for three years.

He then went to the University of California, Berkeley. He first studied chemistry but switched to theoretical physics when he found out his old high school physics teacher was there. Condon earned his bachelor's degree in three years and his doctorate (Ph.D.) in two. His Ph.D. work led to the Franck–Condon principle, which describes how molecules absorb and emit light.

With a special fellowship, Condon studied in Germany under famous physicists like Max Born and Arnold Sommerfeld. He later worked at Bell Telephone Laboratories, helping to share their discovery of electron diffraction.

Career in Science

Early Work

Condon taught physics at Columbia University and Princeton University from 1928 to 1937. In 1929, he co-wrote Quantum Mechanics, which was the first English textbook on the subject. He also co-wrote Theory of Atomic Spectra in 1935, which became a very important book in the field.

In 1937, he joined the Westinghouse Electric Company in Pittsburgh. There, he started research programs in nuclear physics, solid-state physics, and mass spectroscopy. He also led the company's work on microwave radar and helped with equipment used to separate uranium for atomic bombs. In 1940, Condon showed off his machine called the Nimatron at the New York World Fair. He even got a patent for this innovative machine.

Government Service

In 1943, Condon joined the Manhattan Project, a secret World War II effort to build the first atomic bombs. However, he resigned after only six weeks due to disagreements about security rules with the project's military leader, General Leslie R. Groves. Condon felt the extreme security was "morbidly depressing."

After the war, Condon played a big role in getting scientists to push for civilian control of atomic energy, rather than military control. He helped write the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which created the United States Atomic Energy Commission to manage atomic energy under civilian leadership.

In 1945, President Harry S. Truman nominated Condon to be the director of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), which is now called NIST. The Senate approved his nomination, and Condon served as NBS director until 1951. He was also president of the American Physical Society in 1946.

Facing Accusations

1940s Challenges

During the 1940s, Condon's security clearance, which allowed him to access secret information, was often questioned. However, each time, his clearance was re-approved.

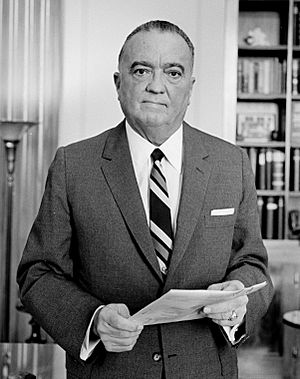

In 1947, Congressman J. Parnell Thomas, who led the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), publicly questioned Condon's loyalty. HUAC was a committee that investigated people suspected of being disloyal to the United States. Thomas used the situation to gain attention and support for his committee.

Despite these attacks, the Department of Commerce cleared Condon of any disloyalty charges in February 1948. However, HUAC continued to claim that Condon was a "weak link" in atomic security. Condon famously responded that if he was the weakest link, the country was "absolutely safe" because he was completely loyal.

Many people, including Senator Dennis Chávez, spoke out against the unfair attacks on Condon. They pointed out that Condon was being "persecuted" just because he had talked to people from other countries or because he was appointed by Henry Wallace, a former Vice President.

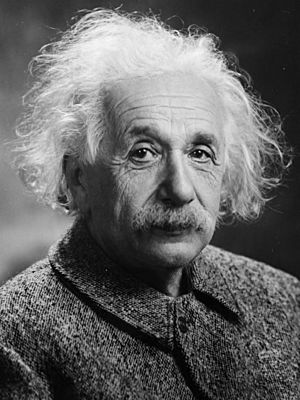

Famous scientists like Albert Einstein and Harold Urey defended Condon. The entire physics department at Harvard University and many scientific organizations wrote to President Truman to support Condon. In September 1948, President Truman himself publicly criticized HUAC, saying their actions were "the most un-American thing we have to contend with today."

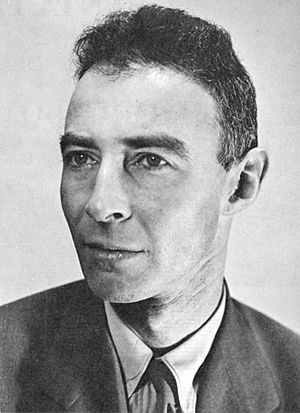

Condon believed that scientists should not cooperate with Congressional attempts to find security risks. In 1949, he criticized J. Robert Oppenheimer for giving information about a colleague to HUAC. Condon also testified before a Senate committee, criticizing HUAC for holding secret hearings and then leaking information that harmed his reputation and that of other scientists.

1950s Challenges

In 1951, Condon left his government job to become the head of research at Corning Glass Works. President Truman praised Condon's loyal service. However, some politicians still claimed Condon was leaving under investigation, which was denied by the Secretary of Commerce.

In 1952, Condon finally had the chance to deny all charges of disloyalty under oath before a Congressional committee. Despite this, HUAC continued to claim he was unsuitable for a security clearance. In December 1952, Condon became president of the AAAS. His fellow scientists gave him a huge ovation, showing their trust in him.

His security clearance was revoked again in 1954, which was common when someone left government work. It was then granted again, but quickly suspended. Condon eventually gave up trying to get his clearance back and resigned from Corning. He felt the government was unfairly targeting scientists.

Years later, Carl Sagan shared a story about Condon's encounter with a loyalty review board. A board member questioned Condon about being at the "forefront of a revolutionary movement in physics called... quantum mechanics." The board member suggested that if Condon could lead one revolutionary movement, he might lead another. Condon reportedly replied by listing many well-known scientific principles from past centuries, showing his belief in established science. He once said privately that he joined any organization with "noble goals" and didn't worry if it included people with different political views.

Later Academic Life

Condon became a physics professor at Washington University in St. Louis from 1956 to 1963. He then moved to the University of Colorado Boulder in 1963, where he taught until he retired in 1970.

From 1966 to 1968, Condon led the Boulder UFO Project, also known as the Condon Committee. He was chosen because of his respected reputation and because he didn't have strong opinions about UFOs. The committee's final report in 1968 concluded that most unidentified flying objects had ordinary explanations. This report played a big role in why mainstream scientists became less interested in UFOs.

Condon also served as president of the American Institute of Physics and the American Association of Physics Teachers in 1964. He was also involved in groups promoting social responsibility in science and nuclear disarmament.

Global Policy

Condon was one of the people who signed an agreement to hold a meeting to create a world constitution. This led to the first-ever World Constituent Assembly, which worked to draft a Constitution for the Federation of Earth.

Personal Life and Death

In 1922, Condon married Emilie Honzik. They had two sons and a daughter. One of their sons, Joseph Henry Condon, became a physicist and engineer who helped invent the Belle chess computer.

Edward Condon was a Quaker and described himself as a "liberal." He died on March 26, 1974, in Boulder, Colorado, at the age of 72. His wife, Emma, passed away seven months later.

Legacy

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) gives an annual award named after Condon. The Condon Award recognizes excellent writing in science and technology at NIST. This award started in 1974.

The crater Condon on the Moon is named in his honor.

A fellow physicist, Philip Morse, described Condon's impact by quoting Lewis Branscomb: "Watergate came as no surprise to Edward Condon, nor did its aftermath. I imagine he would like to have lived to see the outcome of the impeachment inquiry. But Condon understood and paid his share of the price of liberty. Somehow his idealism, his sense of humor and his inexhaustible energy made his relentless quest for a better world look like optimism."

See also

In Spanish: Edward Condon para niños

In Spanish: Edward Condon para niños

- Ronald Wilfred Gurney

- Quantum tunnelling

- McCarthyism

- Anti-communism

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |