Elizabeth Dilling facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elizabeth Dilling

|

|

|---|---|

Elizabeth Dilling speaking to a Senate committee in 1939

|

|

| Born |

Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick

April 19, 1894 Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Died | April 30, 1966 (aged 72) Lincoln, Nebraska, U.S.

|

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 2 |

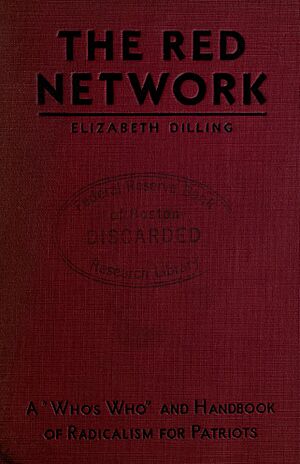

Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick Dilling (born April 19, 1894 – died April 30, 1966) was an American writer and political activist. She became well-known in the 1930s for her strong opinions. In 1934, she published a book called The Red Network. This book listed over 1,300 people she believed were communists or supported communist ideas.

Her books and speeches made her a leading right-wing activist during the 1930s. She was a strong critic of the New Deal, which was a series of programs and reforms in the United States. In the mid-to-late 1930s, Dilling showed support for Nazi Germany. During World War II, she was a key leader in the women's isolationist movement. This movement wanted the United States to stay out of the war and not help the Allies. In 1942, she was among 28 anti-war campaigners who faced charges related to their activities, but these charges were later dropped in 1946.

Contents

Elizabeth Dilling's Early Life

Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick was born on April 19, 1894, in Chicago, Illinois. Her father, Lafayette Kirkpatrick, was a surgeon. Her mother, Elizabeth Harding, sold real estate to help the family after her father died when Elizabeth was very young. Elizabeth had an older brother, Lafayette, who became wealthy from developing properties in Hawaii.

Elizabeth grew up in the Episcopal Church. She also attended a Catholic girls' school called Academy of Our Lady. She was very religious and sometimes sent long letters about the Bible to her friends.

Education and Marriage

In 1912, Elizabeth started studying music and languages at the University of Chicago. She hoped to become a musician who played in an orchestra. She learned to play the harp. After three years, she left the university without finishing her degree.

In 1918, she married Albert Dilling, an engineer who was also studying law. They both attended the same church. The couple had a good financial situation because of money Elizabeth inherited and Albert's job as a chief engineer. They lived in Wilmette, a suburb of Chicago, and had two children: Kirkpatrick, born in 1920, and Elizabeth Jane, born in 1925.

Travels and Political Views

Between 1923 and 1939, Elizabeth and her family traveled abroad many times. These trips helped shape her political ideas. She became convinced that America was the best country.

In 1923, they visited Britain, France, and Italy. Elizabeth felt that the British were not thankful enough for America's help in World War I. Because of this, she decided she would oppose any future American involvement in European conflicts.

In 1931, they spent a month in the Soviet Union. Elizabeth claimed that their local guides, whom she said were Jewish, told her that communism would take over the world. They even showed her a map of the U.S. with cities renamed after Soviet heroes. She recorded her travels using home movies.

Dilling also visited Germany in 1931 and again in 1938. She noticed a "great improvement" in Germany during her second visit. She went to Nazi Party meetings, and the German government paid for her trip. She wrote that "The German people under Hitler are contented and happy."

In 1938, she toured Palestine. There, she filmed what she described as Jewish immigrants harming the country. While visiting Spain during the Spanish Civil War, she filmed burnt churches that she believed were destroyed by "Reds" with "satanic Jewish glee." She also visited Japan, which she saw as the only Christian nation in Asia.

Fighting Communism

Elizabeth Dilling's political activism grew stronger after her trip to the Soviet Union in 1931. She faced "bitter opposition" when she returned to Illinois and tried to share what she had seen. Her doctor suggested public speaking as a hobby.

Iris McCord, a radio broadcaster in Chicago, helped Dilling arrange speeches for local church groups. Within a year, Dilling was traveling across the Midwest, Northeast, and sometimes the West Coast. Her husband often joined her. She showed her home movies of the Soviet Union and gave the same speech many times a week. Audiences, sometimes hundreds of people, were hosted by groups like the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and the American Legion.

Starting Anti-Communist Groups

In 1932, Dilling helped start the Paul Reveres, an anti-communist group based in Chicago. This group eventually had 200 local chapters. She left the group in 1934 after a disagreement.

With encouragement from Iris McCord, Dilling's speeches were published in a local newspaper in 1932. These articles were then put together into a pamphlet called Red Revolution: Do We Want It Here? Dilling claimed that the DAR printed and gave out thousands of copies.

The Red Network Book

Starting in early 1933, Dilling spent many hours researching and listing people she thought were trying to cause trouble. She used reports from government committees as her sources. The result of her work was The Red Network—A Who's Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots.

This 352-page book had essays in the first half. The second half described more than 1,300 "Reds," including famous people like Albert Einstein. It also listed over 460 organizations that she called "Communist, Radical Pacifist, Anarchist, Socialist," or controlled by the I.W.W..

The book was reprinted eight times and sold over 16,000 copies by 1941. Thousands more were given away. It was sold in bookstores and by mail from Dilling's home. Groups like the KKK and the German-American Bund distributed it. Police departments and the Federal Bureau of Investigation also bought copies.

Accusations Against Universities

In 1935, Dilling returned to her old university, the University of Chicago. She accused people like the university president, Robert Maynard Hutchins, and activist Jane Addams of supporting communism. A retail business owner, Charles R. Walgreen, asked for her help after his niece said professors at the university were communists. They demanded the university be closed. The Illinois legislature looked into the matter but decided the claims were not true.

Dilling gave a passionate speech at the Illinois General Assembly. She said, "It is certain that the University of Chicago is diseased with Communism."

Later Books and Research

Dilling's next book, The Roosevelt Red Record and Its Background, was published in 1936. It was less successful. She later claimed that her first two books helped lead to the creation of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1938, Dilling started the Patriotic Research Bureau. This was a large archive in Chicago with staff who were "Christian women and girls." She began publishing the Patriotic Research Bulletin, a newsletter with her political and personal views. She sent it for free to her supporters.

In 1939, industrialist Henry Ford paid Dilling $5,000 to investigate communism at the University of Michigan. Dilling found hundreds of books at the university library written by "radicals." Her report said the university was "typical of those American colleges which have permitted Marxist-bitten, professional theorists to inoculate wholesome American youths with their collectivist propaganda." She came to similar conclusions when she investigated UCLA and her children's universities, Cornell and Northwestern.

In 1940, Dilling published The Octopus. This book shared her ideas about communism and Jewish people. She used the fake name "Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson" for this book. She later admitted she wrote it during her divorce trial in 1942.

Opposing War (Isolationism)

Elizabeth Dilling was a key figure in a large movement of women's groups who wanted the U.S. to stay out of World War II. These groups believed that war was against the idea of nurturing motherhood. They argued that as women, they had a special reason to prevent America from joining the European conflict. These arguments were often mixed with right-wing, anti-Roosevelt, anti-British, and anti-communist ideas.

This movement was strongest in the Midwest, a conservative area. Chicago was a center for many far-right activists and the America First Committee, which had 850,000 members by 1941. Dilling spoke at America First meetings. She also helped start "We the Mothers Mobilize for America," a very active group with 150,000 members.

In early 1941, Dilling spoke at rallies in the Midwest. She formed a group called the "Mothers' Crusade to Defeat H. R. 1776" to oppose the Lend-Lease Act. Hundreds of these activists protested at the Capitol for two weeks in February 1941. Dilling was arrested when she led a sit-down protest with other protesters outside a senator's office. After a six-day trial, she was found guilty of disorderly conduct and fined $25.

Many of the women's groups continued to oppose the war even after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Dilling campaigned for Thomas E. Dewey in the 1944 presidential election. Her political activity slowed down because of her highly publicized divorce trial, which began in February 1942.

In 1942, Dilling and 27 other anti-war activists were accused of trying to undermine the military during peacetime and wartime. This case was part of a government effort against groups seen as a threat at home. The judge in the case died in 1944, and a new judge declared a mistrial. The charges were finally dropped in 1946 because the government could not present strong new evidence.

After the War

After the trial ended in 1946, Dilling continued to publish her Patriotic Research Bulletin. In 1964, she published The Plot Against Christianity. After she died, this book was renamed The Jewish Religion: Its Influence Today.

Elizabeth Dilling passed away on April 30, 1966, in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Works

Elizabeth Dilling self-published the first versions of her books in Kenilworth, Illinois. Later, other publishers reprinted them.

Books by Elizabeth Dilling

- The Red Network, A "Who's Who" and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots (1934)

- "Lady Patriot" Replies (1936)

- The Roosevelt Red Record and Its Background (1936)

- Dare We Oppose Red Treason? (1937)

- The Red Betrayal of the Churches (1938)

- The Octopus, by Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson (1940)

- The Plot Against Christianity (1964)

- Also known as The Jewish Religion: Its Influence Today

See also

In Spanish: Elizabeth Dilling para niños

In Spanish: Elizabeth Dilling para niños

- Blair Coan

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |