Emperor penguin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Emperor penguin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Adults with a chick on Snow Hill Island, Antarctic Peninsula | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Aptenodytes

|

| Species: |

forsteri

|

|

|

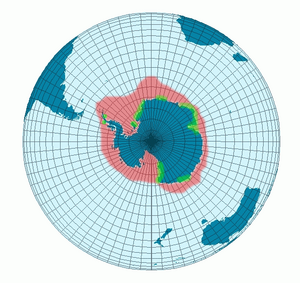

| Emperor penguin range (breeding colonies in green) |

|

The emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species. These amazing birds live only in Antarctica, the coldest place on Earth.

Contents

How the Emperor Penguin Got Its Name

The emperor penguin was first described in 1844 by an English zoologist named George Robert Gray. Its scientific name, Aptenodytes forsteri, comes from old Greek words. These words mean "diver without wings," which is a perfect description for a bird that swims so well but cannot fly!

What Does an Emperor Penguin Look Like?

Adult emperor penguins are quite tall, standing about 110–120 cm (43–47 in) (around 4 feet) from their beak to their tail. They are also very heavy, weighing between 22.7 to 45.4 kg (50 to 100 lb) (50 to 100 pounds). Male penguins usually weigh a bit more than females. Their weight can also change depending on the season.

Like all penguins, emperor penguins have bodies shaped like torpedoes. This helps them glide easily through the water when they swim. Their wings are not like bird wings for flying. Instead, they are stiff, flat flippers that help them "fly" underwater. Their tongues have special hooks pointing backward. These hooks stop their prey from escaping once caught.

Both male and female emperor penguins look very similar. They have deep black feathers on their head, chin, throat, back, flippers, and tail. Their bellies and the underside of their wings are white. Their upper chest has a pale yellow color, and they have bright yellow patches near their ears.

What Do Emperor Penguins Eat?

Emperor penguins mostly eat fish. They also enjoy crustaceans like tiny krill, and cephalopods such as squid.

Fish are usually the most important part of their diet. The Antarctic silverfish (Pleuragramma antarcticum) is a favorite meal. Emperor penguins hunt for their food in the open waters of the Southern Ocean. One clever way they hunt is by diving about 50 m (160 ft) (164 feet) deep. Here, they can easily spot fish swimming against the bottom of the sea ice. They then swim up to the ice and catch the fish. They might repeat this diving and catching several times before coming up for air.

Where Do Emperor Penguins Live?

Emperor penguins live almost only in Antarctica, between 66° and 77° south latitudes. This is a very cold and icy part of the world!

The most northern group of breeding penguins is found on Snow Island. This island is close to the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. Sometimes, individual penguins have been seen in other places like Heard Island, South Georgia, and even New Zealand.

In 2009, scientists estimated there were about 595,000 adult emperor penguins. They lived in 46 known groups, called colonies, spread around Antarctica. About 35% of these penguins live north of the Antarctic Circle. In 2022, a new colony was found by satellite, bringing the total known colonies to 66!

Who Hunts Emperor Penguins?

Emperor penguins have predators that hunt them, including birds and sea mammals.

- The Southern giant petrel (Macronectes giganteus) hunts young chicks. These birds are responsible for over a third of chick deaths in some colonies. They also eat dead penguins.

- The south polar skua (Stercorarius maccormicki) mainly eats dead chicks.

- Sometimes, a parent penguin tries to protect its chick from an attack. However, if the chick is weak, the parent might not fight as hard.

The only known predators that attack healthy adult emperor penguins in the water are mammals:

- The leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) hunts adult birds and young penguins (fledglings) soon after they enter the water.

- Orcas (Orcinus orca) mostly hunt adult penguins. However, they will attack penguins of any age in or near the water.

How Emperor Penguins Survive the Cold

Staying Warm in Antarctica

Emperor penguins have amazing ways to stay warm in the freezing Antarctic.

- Their feathers are very thick and provide 80–90% of their body's insulation. This means they trap a lot of heat.

- They also have a thick layer of fat under their skin, which can be up to 3 cm (1.2 in) (about 1.2 inches) thick. This fat acts like a warm blanket.

- On land, they can make their feathers stand up. This traps a layer of air next to their skin, which helps reduce heat loss.

- When they are in the water, their feathers flatten. This makes their skin waterproof and keeps the soft, downy feathers underneath dry.

- Emperor penguins can control their body temperature without changing how much energy they use. This is called thermoregulation.

Surviving Deep Dives

Emperor penguins are incredible divers! They have special adaptations to handle the pressure and low oxygen deep underwater:

- Their bones are solid, not hollow like most birds. This helps them avoid problems from the high pressure deep in the ocean.

- When diving, their heart rate slows down to as low as 15–20 beats per minute. This helps them use less oxygen.

- They can also temporarily shut down organs that are not essential for diving. These adaptations allow them to stay underwater for a long time.

Emperor Penguin Life Cycle and Reproduction

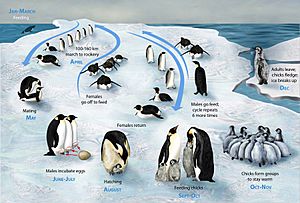

The emperor penguin is the only penguin species that breeds during the harsh Antarctic winter. Their breeding colonies are usually in places where ice cliffs and icebergs offer some protection from strong winds.

Emperor penguins are "serially monogamous." This means they have only one mate each year and stay with that mate for the breeding season. However, they do not mate for life. Only about 15% of pairs stay together for more than one year.

The female lays a single egg in May or early June. She then carefully passes the egg to the male. This can be tricky, especially for new parents. Many couples accidentally drop or crack the egg. If an egg is lost this way, the pair breaks up and returns to the sea. They will try to find new mates next year.

If the egg is transferred successfully, the female leaves for the sea to hunt for food. The male then spends the dark, stormy winter incubating (warming) the egg. He must endure extreme cold for over two months, protecting the egg without eating anything. Most male emperors lose about 12 kg (26 lb) (26 pounds) during this time. This behavior is unique to emperor penguins. In all other penguin species, both parents take turns incubating the egg.

The chick usually hatches before the mother returns. The father feeds the chick a special curd-like substance. This "crop milk" is made of protein and fat from a gland in his throat. This ability to produce milk is very rare in birds. It is only found in pigeons, flamingos, and male emperor penguins. The father's crop milk can keep the chick alive for about 4 to 7 days until the mother returns with real food from the sea. If the mother is delayed, the chick might not survive.

Once the chick hatches, both parents take turns. One parent goes to sea to find food, while the other stays in the colony to care for the chick.

Emperor penguin chicks are covered in soft, silver-grey down feathers. They have black heads and white "masks." Chicks weigh about 315 g (11 oz) (11 ounces) when they hatch. They are ready to leave the colony when they reach about half the weight of an adult.

Sometimes, female penguins who didn't find a mate or lost their own chick might try to adopt a stray chick or even steal one from another female. The mother of the chick and other nearby females will fight to protect their chick. Chicks that are adopted or stolen are often abandoned again quickly. This is because a single female cannot feed and care for a chick alone. These orphaned chicks wander around the colony, trying to find food and protection. They might even try to hide under an adult bird that already has its own chick. However, these stray chicks are usually pushed away by the adults. Sadly, all orphaned chicks quickly become weak and die from hunger or freezing.

Conservation Status: Are Emperor Penguins in Danger?

In 2012, the emperor penguin's conservation status was changed from "least concern" to "near threatened" by the IUCN. This means they are getting closer to being endangered. Along with nine other penguin species, they are being considered for protection under the US Endangered Species Act.

Emperor penguins are very sensitive to changes in the climate. As the sea ice melts due to global warming, their habitat is being destroyed. Less ice also means less krill, which is a main food source for them. The impact of tourism is also a concern.

A study in 2009 suggested that emperor penguins could be close to extinction by the year 2100. This study used a mathematical model to predict how melting sea ice would affect a large colony in Adélie Land, Antarctica. It predicted an 87% drop in the colony's population, from three thousand breeding pairs in 2009 to only four hundred by 2100.

Another study in 2014 also warned that all 45 colonies of emperor penguins would likely decline in numbers by 2100. This is mainly due to the loss of their icy habitat from global warming.

Emperor Penguins and Humans

Emperor Penguins in Zoos and Aquariums

Since the 1930s, people have tried to keep emperor penguins in zoos. Early attempts were often unsuccessful because not much was known about how to care for penguins.

One of the first successful places was Aalborg Zoo, where a special chilled house was built for these Antarctic birds. One penguin lived there for 20 years, and a chick even hatched, though it didn't survive long.

Today, only a few zoos and aquariums in North America and Asia keep emperor penguins. SeaWorld San Diego was the first to successfully breed them, with over 20 chicks hatching there since 1980. In China, emperor penguins were first bred in 2009 at Nanjing Underwater World. In Japan, they are housed at Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium and Adventure World.

Penguin Rescue and Rehabilitation

In June 2011, a young emperor penguin was found on a beach in Peka Peka, New Zealand. This penguin, nicknamed "Happy Feet" (after the movie), had eaten 3 kg (6.6 lb) (6.6 pounds) of sand, sticks, and stones. He probably thought the sand was snow! He needed several operations to remove these items and save his life.

After he recovered, Happy Feet was fitted with a tracking device. On September 4, he was released into the Southern Ocean, about 80 km (50 mi) (50 miles) north of Campbell Island. However, scientists lost contact with him 8 days later. It's thought his transmitter fell off, which is common.

Cool Facts About Emperor Penguins

- The emperor penguin is the fifth heaviest living bird species on Earth.

- Male emperor penguins are amazing dads! They take care of the eggs, keeping them warm and safe for two months before the chicks hatch.

- Sadly, only about 19% of emperor penguin chicks survive their first year of life.

- About 80% of the emperor penguin population are adults aged five years or older.

- Emperor penguins can live up to 20 years in the wild, and some have even lived up to 50 years!

- They shed all their feathers (moult) every year in January and February. This process takes about 34 days.

- While hunting, they can stay underwater for around 20 minutes. They can dive to an incredible depth of 535 m (1,755 ft) (1,755 feet)!

- In 1994, one penguin from Auster rookery dove to an amazing depth of 564 meters (1,850 feet). This entire dive lasted 21.8 minutes!

- Emperor penguin breeding colonies can have thousands of individual birds.

- They breed in the coldest environment of any bird species. Air temperatures can drop to −40 °C (−40 °F) (–40°F), and winds can reach 144 km/h (89 mph) (90 mph).

- Emperor penguins use special calls to talk to each other. They can even use two different sound frequencies at the same time!

- Chicks use a special whistle sound to ask for food and to find their parents.

- Emperor penguins are very strong birds. Once, six men tried to capture a single male penguin for a zoo. The penguin, which weighs about half as much as a man, repeatedly tossed and knocked over the men before they finally managed to tackle it together!

- To stay warm in the extreme cold, a colony of emperor penguins forms a tight huddle. They slowly shuffle around, giving every bird a turn in the warmer middle and on the colder outside.

- Emperor penguins are very social animals. They hunt together and even coordinate their dives and when they surface for air.

See also

In Spanish: Pingüino emperador para niños

In Spanish: Pingüino emperador para niños