English National Opera facts for kids

The English National Opera (ENO) is a famous opera company in London, England. They perform at the London Coliseum theatre. What makes ENO special is that all their operas are sung in English! This helps more people understand the stories and enjoy the music. ENO is one of the two main opera companies in London, the other being The Royal Opera.

The company started a long time ago, in the late 1800s. A kind lady named Emma Cons and her niece Lilian Baylis wanted to bring theatre and opera to everyone, not just the rich. They started by putting on shows at a theatre called the Old Vic. Over time, their work grew into three big arts groups: the English National Opera, the Royal National Theatre (for plays), and The Royal Ballet (for dance).

Lilian Baylis later bought and rebuilt a bigger theatre called Sadler's Wells in north London. This new theatre was much better for opera. The opera company became a full-time group in the 1930s. During World War II, the theatre closed, and the company traveled around Britain performing. After the war, they returned home and kept getting better. By the 1960s, they needed an even bigger place. So, in 1968, the company moved to the London Coliseum. In 1974, they officially changed their name to the English National Opera.

Many famous conductors have worked with ENO, like Colin Davis and Charles Mackerras. The current music director is Martyn Brabbins. Well-known directors, such as Jonathan Miller and Nicholas Hytner, have also created amazing shows for ENO. The current artistic director is Annilese Miskimmon. ENO performs many different types of shows, from old operas by composers like Monteverdi to brand new operas and even Broadway musicals.

Contents

History

Early Beginnings

In 1889, Emma Cons started showing parts of operas at the Old Vic theatre. This theatre was in a working-class area of London. Even though she couldn't put on full shows with costumes, she presented shorter versions of popular operas. All the songs were in English. These opera nights quickly became more popular than the plays she was showing.

In 1898, Emma asked her niece, Lilian Baylis, to help run the theatre. They both believed that opera should be for everyone, not just the wealthy. They worked with a very small budget, using amateur singers and a small orchestra. By the early 1900s, the Old Vic was even able to perform parts of Wagner's famous operas.

Emma Cons passed away in 1912, leaving the Old Vic to Lilian Baylis. Lilian dreamed of making it a "people's opera house." That same year, she got permission to put on full opera performances. She focused a lot on opera, even though her Shakespeare plays were also very popular.

The Vic-Wells Era

By the 1920s, Baylis realized the Old Vic was too small for both her theatre and opera groups. She found an empty theatre called Sadler's Wells on the other side of London. She wanted to run both theatres together.

Baylis asked the public for money in 1925. With help from the Carnegie Trust and many others, she bought Sadler's Wells. Work began in 1926, and by Christmas 1930, a brand new theatre with 1,640 seats was ready! The first opera there was Carmen on January 20, 1931.

Running the new theatre was more expensive. A bigger orchestra and more singers were needed. At first, not enough tickets were sold. Some people thought the opera performances weren't as good as the plays. Baylis worked hard to make the opera better. She also stopped Sir Thomas Beecham from trying to combine her opera company with his, as she wanted her company to stay focused on its regular audience.

By 1934, the Old Vic became the home for plays, and Sadler's Wells housed both the opera and a new ballet company. The ballet company, started by Baylis and Ninette de Valois, helped pay for the expensive opera shows. The orchestra grew to 48 players. Singers like Joan Cross and Edith Coates performed with the company. They performed many well-known operas by composers like Mozart and Verdi, as well as lighter shows.

Lilian Baylis died in November 1937. Her three companies continued under new leaders. During World War II, Sadler's Wells theatre was used to help people who lost their homes. The opera company became a small touring group of 20 performers. They traveled constantly, visiting 87 different places between 1942 and 1945. Joan Cross led the company and also sang in the shows. By 1945, the company had grown to 80 members.

Sadler's Wells Opera Grows

After World War II, the government wanted to help opera in Britain. They decided to create a new company at Covent Garden that would perform all year in English. This was similar to Sadler's Wells. However, the manager of Covent Garden didn't want to combine the two opera companies. He thought Sadler's Wells was "dowdy" (old-fashioned). Sadler's Wells also wanted to keep its own name and history. So, the two companies stayed separate.

There were some disagreements within the Sadler's Wells company. Joan Cross wanted to reopen the theatre with a new opera called Peter Grimes by Benjamin Britten. Some people complained about this new opera. But when Peter Grimes opened in June 1945, it was a big success! However, the disagreements continued. Joan Cross, Benjamin Britten, and others left Sadler's Wells and started their own group. The ballet company also moved to Covent Garden, which meant Sadler's Wells lost a lot of money because the ballet had helped pay for the opera.

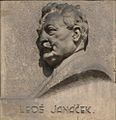

Clive Carey came back to lead Sadler's Wells and rebuild the company. By 1950, Sadler's Wells received £40,000 a year from the government, while Covent Garden received much more. To make the shows more exciting, Sadler's Wells hired famous theatre directors. They also started performing new operas, like the first British show of Janáček's Káťa Kabanová. The company's quality and spirit improved greatly.

The company continued to tour British cities in the summer. There were talks about building a new home for Sadler's Wells, but the government wouldn't pay for it. There were also talks again about combining Covent Garden and Sadler's Wells. Instead, Sadler's Wells decided to work more closely with another touring company, Carl Rosa. In 1960, the Carl Rosa Company closed, and Sadler's Wells took on some of its members and touring dates. They created two groups that could switch between performing in London and touring.

By the late 1950s, Covent Garden started performing more operas in their original languages, not just English. This made Sadler's Wells unique because they continued to sing all operas in English. Sadler's Wells focused on young British singers, while Covent Garden used international stars. Colin Davis became the musical director in 1961. They continued to perform both well-known and new operas. In 1962, they performed their first Gilbert and Sullivan opera, Iolanthe, which was very popular.

The Islington theatre was becoming too small for the growing company. In 1958, a popular show called The Merry Widow moved to the much larger London Coliseum for a summer. Ten years later, the Coliseum became available for rent. Stephen Arlen, the managing director, pushed for the company to move there. After a lot of talks and fundraising, they signed a ten-year lease in 1968. One of their last shows at the Islington theatre was Wagner's The Mastersingers, which became famous. Their last performance there was on June 15, 1968.

Moving to the Coliseum

The company, still called "Sadler's Wells Opera," opened at the Coliseum on August 21, 1968. They performed Mozart's Don Giovanni. Even though this first show wasn't a big hit, the company quickly became known for many excellent productions. Stephen Arlen died in 1972, and Lord Harewood took over as managing director.

The success of The Mastersingers in 1968 led to the company's first full Ring cycle by Wagner in the 1970s. This was a huge project! Lord Harewood felt that the Ring cycle, along with Prokofiev's War and Peace and Strauss's Salome, were some of the best shows in their first ten years at the Coliseum.

Charles Mackerras was the company's musical director from 1970 to 1977. He was praised for being able to conduct many different types of operas. He conducted Handel's Julius Caesar with famous singer Janet Baker, five Janáček operas, and even Gilbert and Sullivan's Patience. The company took Patience to the Vienna Festival in 1975. Sir Charles Groves followed Mackerras, and then Mark Elder became the musical director in 1979.

A big goal for the company was to change its name. People kept going to the old Sadler's Wells theatre by mistake! Lord Harewood believed it was important not to use the name of a theatre they no longer performed in. Other opera companies didn't want them to be called "The British National Opera." Finally, the British government decided, and the name "English National Opera" was approved in November 1974. In 1977, a second company was started in Leeds to perform for people in other parts of England. This company became independent in 1981 and is now called Opera North.

ENO in Recent Years

In the 1980s, Mark Elder, David Pountney (director of productions), and Peter Jonas (managing director) led ENO. They were known as the "Powerhouse" and wanted to create new, exciting, and sometimes risky opera productions. They wanted to explore the deeper meanings in the operas. For example, their production of Rusalka in 1983 had a dream-like setting, and Hansel and Gretel in 1987 featured fantasy characters.

However, ticket sales sometimes went down, and there were money problems. After 1983, the company stopped touring to other British cities. Despite challenges, ENO was seen as different from Covent Garden, more focused on the theatrical side. In the 1980s, ENO performed operas like Pelléas and Mélisande and Parsifal for the first time. Some productions, like Xerxes and Rigoletto, stayed popular for many years.

In 1984, ENO toured the United States, performing at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. This was the first time a major British opera company had been invited there. Their production of Patience received a standing ovation, and their Rigoletto, set with characters like mafiosi, caused a lot of discussion. In 1990, ENO was the first big foreign opera company to tour the Soviet Union.

The "Powerhouse" era ended in 1992. Dennis Marks became the new general director, and Sian Edwards became the new music director. Marks worked hard to improve the company's finances by selling more tickets. A new production of Der Rosenkavalier was very successful. Marks also worked to get funding to fix up the Coliseum, which ENO bought in 1992. After some criticism, Edwards resigned in 1995, and Paul Daniel became the next music director.

Daniel took over a company that was doing well artistically and financially. He fought against another idea to combine Covent Garden and ENO, which was quickly dropped. In 1998, Nicholas Payne became ENO's general director. In the 1990s, ENO started doing more "co-productions" with other opera houses to share costs.

2000s and Beyond

In 2001, Martin Smith became chairman of the ENO board. He was good at raising money and even gave £1 million himself to help fix the Coliseum. However, he disagreed with Nicholas Payne about some of the "director's opera" productions, especially a very controversial Don Giovanni in 2001. Critics and audiences disliked it. Because of these disagreements, Payne had to resign in 2002.

Séan Doran took over, even though he hadn't run an opera company before. He tried new things, like performing parts of an opera at the Glastonbury Festival for rock music fans. In 2005, Paul Daniel announced he would leave.

In 2004, ENO started its second production of Wagner's Ring cycle. The shows were directed by Phyllida Lloyd. While some early parts of the cycle received criticism, things improved by the end.

In the 2000s, ENO also performed oratorios (choral works) like St. John Passion and Verdi's Requiem as if they were operas. They also performed more of Handel's operas. In 2005, ENO decided to start using surtitles (words projected above the stage) because many audience members couldn't understand the English words being sung. Some people disagreed with this, saying it would make singers less clear.

In 2005, Doran resigned. The company's leadership changed, and Edward Gardner became the music director in 2007. He was praised for bringing new energy to ENO. Ticket sales improved, especially with younger audiences, and the company's finances got better.

In the 2010s, ENO continued to work with directors from outside the opera world, like Terry Gilliam. They also started "Opera Undressed" evenings to attract new audiences who thought opera was "too pricey, too pompous, too posh."

In 2014, Gardner announced he would leave, and Mark Wigglesworth was named his successor. Around this time, ENO faced more money problems and changes in leadership. The Arts Council England, which provides government funding, had serious concerns about ENO's plans. In 2015, Cressida Pollock became the interim CEO, and John Berry resigned as artistic director.

Despite the challenges, ENO had successful shows like The Mastersingers and Sweeney Todd in 2014–2015. In 2016, Mark Wigglesworth resigned as music director. Daniel Kramer became the new artistic director, and Martyn Brabbins became the new music director.

In 2018, ENO started offering free tickets to young people under 18 on Saturdays, and later expanded this to under 21s for all performances. This was to encourage more young people to experience opera.

In 2022, Arts Council England decided to remove ENO from its main funding list, which meant a big cut in money. ENO first said they would look for a new base outside London, possibly in Manchester. But then they asked for their funding to be put back and to keep their London home. In 2023, a deal was made: ENO would get funding until 2024 to keep performing in London, and also plan for a new base outside London by 2026.

In October 2023, Martyn Brabbins resigned as music director because of proposed cuts to the music staff. In December 2023, it was announced that ENO would set up its main base in Greater Manchester by 2029.

What ENO Performs

ENO aims to perform well-known operas, always sung in English. They have staged all the major operas by Mozart, Wagner, and Puccini, and many by Verdi. They also perform many Czech, French, and Russian operas. ENO focuses on opera as a dramatic story, not just about showing off singing skills. They also have a history of performing new works and asking composers to write new operas for them.

New Operas and First Performances

ENO has asked many composers to write new operas for them. The most famous new opera they first performed was Peter Grimes in 1945. They have also performed the first British stage versions of operas by Verdi, Janáček, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and Philip Glass.

Lighter Shows and Musicals

From the very beginning, ENO has mixed serious operas with lighter shows. After World War II, they started performing operettas (light operas) like The Merry Widow and Die Fledermaus.

The company has also performed most of Gilbert and Sullivan's famous operettas. Their production of Patience was very popular and performed many times. A 1986 production of The Mikado was set in a 1920s English seaside hotel and starred comedian Eric Idle. In 2015, film director Mike Leigh directed The Pirates of Penzance, which was a big hit and broke box-office records for opera shown in cinemas.

Since the 1980s, ENO has also tried performing Broadway musicals, such as Street Scene and On the Town. In 2015, ENO announced a plan to work with West End musical producers to help make money.

Recordings

Sadler's Wells singers made recordings of opera parts from the company's early days. In 1972, an album was released with many of these recordings, featuring singers like Joan Cross and Peter Pears.

After World War II, the Sadler's Wells company made a few more recordings. In the 1950s and 1960s, they recorded shorter versions of operas and operettas for EMI, all sung in English. These included Madame Butterfly and The Merry Widow. They also made a complete recording of The Mikado in 1962.

Later, EMI recorded ENO's complete Ring cycle during live performances between 1973 and 1977. These recordings have been re-released on CD. Other recordings featuring the ENO chorus and orchestra include Lulu, The Makropoulos Affair, and The Barber of Seville.

Education

In 1966, a theatre design course was started at Sadler's Wells, which later became the Motley Theatre Design Course.

ENO Baylis, started in 1985, is the education department of ENO. Its goal is to introduce new people to opera and help current audiences enjoy it more. They offer training for students, workshops, talks, and debates. This program is now called ENO Engage.

Musical directors

- Charles Corri (1898–1935)

- Lawrance Collingwood (chief conductor, 1931–1941, musical director 1941–1946)

- James Robertson (1946–1954)

- Alexander Gibson (1957–1959)

- Colin Davis (1961–1965)

- Mario Bernardi (1966–1968) and Bryan Balkwill (1966–1969), joint musical directors

- Charles Mackerras (1970–1977)

- Sir Charles Groves (1978–1979)

Music directors

- Mark Elder (1979–1993)

- Sian Edwards (1993–1995)

- Paul Daniel (1997–2005)

- Edward Gardner (2007–2015)

- Mark Wigglesworth (2015–2016)

- Martyn Brabbins (2016–2023)

Artistic directors

- John Berry (2005–2015)

- Daniel Kramer (2016–2020)

- Annilese Miskimmon (2020–present)

Images for kids

-

Janáček, a composer whose works were championed by ENO

See also

In Spanish: English National Opera para niños

In Spanish: English National Opera para niños