Environmental justice and coal mining in Appalachia facts for kids

Environmental justice and coal mining in Appalachia looks at how environmental justice connects with coal mining in the Appalachia region. Environmental justice is about making sure everyone, no matter their background, has fair treatment and is involved in decisions about the environment. It also means no group should carry more of the negative environmental effects than others.

The Appalachian region in the Southern United States is a major producer of coal. Studies show that people living near mountaintop removal (MTR) mines often have higher death rates. They are also more likely to live in poverty and face harmful environmental conditions compared to others in the area.

In the late 1990s, women like Julia Bonds started speaking out against MTR. They highlighted its bad effects on people and the environment. Research shows that MTR causes "irreparable" (meaning it can't be fixed) damage. Blasting mountaintops has polluted streams and water supplies. Toxic waste from coal processing, called slurry ponds, has also contaminated water.

Scientists have noticed more breathing and heart problems among people living near mines. This includes lung cancer. Death rates and birth defect rates are higher near surface mining areas.

Coal mining in Appalachia decreased from 1990 to 2015. This happened for several reasons. People wanted more clean energy. New environmental rules from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also played a role. Plus, global changes affected demand.

The number of coal mining jobs stayed steady from 2000 to 2010. But it dropped by 37% between 2011 and 2015. Less coal production caused much of this job loss. However, better mining methods, like mountaintop removal, also meant fewer workers were needed.

Contents

What is Coal Mining in Appalachia?

Where Coal is Found

Appalachia is one of three main coal-mining areas in the United States. The other two are the Interior coal region and the Western coal region, which includes the Powder River Basin. Eight states are part of the Appalachian coal region: Alabama, eastern Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia.

West Virginia produces the most coal in Appalachia. It is the second-largest coal-producing state in the U.S. (after Wyoming). In 2014, West Virginia made about 11% of the nation's total coal. Kentucky and Pennsylvania also produce a lot of coal. They account for 8% and 6% of U.S. coal production, respectively.

The amount of coal produced in Appalachia has changed over time. In 1990, Central Appalachia (southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, western Virginia, and eastern Tennessee) produced almost 29% of U.S. coal. By 2013, this dropped to about 13%. Northern Appalachia's coal production has stayed more stable.

Most coal in the Appalachian region (72%) comes from underground mines. This is different from the Western coal region. There, 90% of all coal comes from surface mines.

A Look Back at Coal Towns

Historically, special "coal towns" were built for miners. This started in the 1880s and was most common in the 1920s. It mostly ended with the Great Depression. At that time, other energy sources like oil, gas, and hydroelectricity became available. This reduced the need for coal.

These company towns were very common in southern Appalachia. In 1925, almost 80% of West Virginia coal miners lived in company towns. In other states like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, about 64% of miners lived in them.

How Coal Mining Affects Appalachia

Since 1995, the Appalachian region has produced about half of the United States' coal. While Appalachia has helped supply the country with coal, the communities near these mines have faced many problems. Studies show differences between mining and non-mining communities. These differences include public health issues, environmental degradation (damage to the environment), pollution, and a lower quality of life.

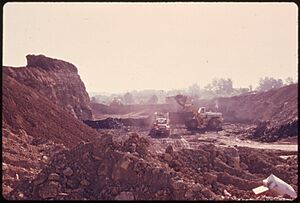

Different types of surface coal mining in Appalachia include contour, area, high-wall, auger, and mountaintop removal mining (MTR).

Surface Mining's Impact

Mountaintop removal strip mining has caused clear damage to the environment and communities in Appalachia. This region has many natural resources, but it remains poor. It also suffers from the negative effects of coal mining, like health problems from coal pollution.

The Office of Surface Mining (OSM) is a government agency. It regulates strip-mining under the Federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA). OSM says that because many low-income people live in coal areas, they are affected more by mountaintop mining. This is an environmental justice issue.

Many local residents cannot easily see how much damage surface mining has caused. A geologist named Sean P. Bemis studied this. Former miner Chuck Nelson told researchers that the destruction is only truly clear from an airplane. Activist Maria Gunnoe said something similar. She stated, "I never realized it was so bad. My first fly-over with South Wings [a non-profit aviation group], and that right there is what really fired me up."

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) confirmed this in a 2009 report. They said the public has limited access to information about these mining operations. This includes their size, location, and what the land will look like after mining stops.

There are no official records of the total "disturbed acres" from surface mining. But studies using satellite images show that between 1.05 million and 1.28 million acres of land have been surface mined. This includes more than 500 mountains in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia.

Mountaintop Removal (MTR)

Mountaintop removal (MTR) is a type of surface mining. This method can remove up to 800 to 1000 feet from mountaintops. It helps reach coal seams that other surface mining methods cannot get to. This practice was small in the 1970s but became very common in the 1990s.

MTR became popular because of a higher demand for high-grade, low-sulfur coal. This demand grew after the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 were passed. The MTR process starts by clearing trees from a mountaintop. Then, explosives are used to blast the mountain.

Next, all the extra soil and rock, called "spoil," is moved away. After mining, this spoil is supposed to be put back. But once the rock is disturbed, it expands by 15% to 25% because air gets into it. This extra spoil, or "overburden," is then dumped into nearby streams or valleys. This is called a valley fill.

Since MTR became popular, about 500 mountaintops have been destroyed. Also, 2000 miles of waterways have been filled. Mountaintop mining and valley fills can cause big changes to the landscape. These changes include breaking up forests, changing habitats, and losing large areas of forest.

There can also be bad effects on people living in these Appalachian mining communities. Michael Hendryx, a researcher, said that about 1,200 more people die each year in these mining communities compared to other parts of Appalachia. The most common diseases in MTR areas are heart disease, lung cancer, and COPD (a lung disease). These are not just problems for miners but for everyone living there. The risk of birth defects, especially heart defects, goes up by 181% in MTR areas. Researchers are now studying tiny particulate matter (small bits of dust) as a cause of these illnesses and higher death rates.

Environmental Damage

Coal surface mining has greatly changed the water cycle and landscape of Appalachia. It has caused environmental damage and harmed ecosystems beyond repair. Surface coal mining in Appalachia has destroyed over 500 mountaintops.

It has also cleared over 1 million acres of forests. From 1985 to 2001, it damaged or permanently lost over 12,000 miles of streams. These streams are very important to the Appalachian watershed (the area of land that drains into a river or lake). Increased saltiness and metal pollution in Appalachian streams have harmed fish and bird species.

Mountaintop removal (MTR) is a major cause of negative environmental impact in Appalachia. When MTR is used, many contaminants from the process are dumped into surrounding valleys. These often flow into nearby streams. These wastes are put into "valley fills," which have collapsed and caused severe flash floods in Appalachia. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that between 1985 and 2001, over 700 miles of streams in the Appalachians were covered by these "valley fills" due to mountaintop removal coal mining.

Social and Economic Effects

Appalachia has historically been one of the most impoverished (poor) regions in the country.

There's a debate about whether coal production brings wealth or poverty to Appalachia. Some studies suggest a "coal-wealth paradox." Appalachia has some of the largest coal mines, but the average income per person is only about 68% of the national average. However, other research shows that from 1970 to 1980, more coal production greatly increased pay for low-skilled workers. This likely reduced income inequality (the gap between rich and poor).

Even though coal mining industries are often linked to more jobs and economic growth, this isn't always true for Appalachia. Two-thirds of the counties there have higher unemployment (people without jobs) than the national average. Also, the average personal wages are 20% lower than the rest of the country.

Counties with coal mining often have greater economic differences and more poverty than counties without the industry. The shift from underground mining to surface mining led to a 50% drop in mining jobs from 1985 to 2005. Competition from cheap natural gas also lowered demand for coal. This caused some mines to close or reduce work, increasing unemployment even more. From 2014 to 2015, overall mining jobs in Appalachia dropped by 15.9%.

A NASA study says that promises of good development after mining in Appalachia have not yet happened. A 2017 study found that neighborhoods closest to coal waste ponds are "slightly more likely to have higher rates of poverty and unemployment."

Important Events

Buffalo Creek Disaster

In 1972, a slurry pond built by Pittson Coal Company broke. This event, known as the Buffalo Creek disaster, released 130 million gallons of sludge (thick, muddy waste) into Buffalo Creek. More recently, a waste pond owned by Massey burst in Kentucky. It flooded nearby streams with 250 tons of coal slurry.

Laws and Regulations for Mining

The Black Lung Benefits Act of 1972 provided payments to coal miners. These payments were for those disabled by Coalworker's pneumoconiosis (also called "black lung disease") and their families.

The 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) created two programs. One was for regulating active coal mines. The second was for reclaiming (fixing up) abandoned mine lands.

According to Jedediah Purdy, the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act improved air and water quality for much of America. However, they also created "sacrificial zones" in America. These included coal mining communities in Appalachia. These laws hid the environmental effects of industry from people in suburbs. But they increased the danger for people living near pollution sites.

These laws, along with the National Environmental Policy Act, form the basis for regulating coal mining. This includes mountaintop removal mining. Rules based on these laws focus on giving or denying permits for new mining operations. However, these rules themselves have been argued about.

As of 2012, these laws did not consider direct effects on communities near mines. They also didn't consider economic or racial differences in those communities. Rules and orders meant to address environmental justice concerns were often stopped. Legal challenges based on possible effects on local communities usually failed. This was because the laws and rules were not written to address these concerns. Judges made decisions based on what the law actually said.

The Affordable Care Act is a federal health care law. It includes parts that change the Black Lung Benefits program. This program details how much of coal miners' medical costs the government pays for. The ACA changes are often called the Byrd Amendments, named after Senator Robert Byrd.

The Byrd Amendments are in Section 1556 of the ACA. They offer many protections for coal miners. For example, they cover medical expenses for miners who worked at least 15 years underground (or similar surface mining). This is for those who have a totally disabling breathing problem. Also, it shifts the responsibility of proving disability from "black lung disease" from the miners back to the coal companies. "Black lung disease" can be a common health problem for retired coal miners.

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977

Early attempts to regulate strip-mining at the state level were not very successful. This was because the rules were not strictly enforced. The Appalachian Group to Save the Land and the People was started in 1965 to stop surface mining. In 1968, Congress held its first hearings on strip mining.

Ken Hechler introduced the first bill to ban strip-mining in Congress in 1971. This bill did not pass. However, some of its ideas became part of SMCRA. These included setting up a way to reclaim abandoned strip mines. It also allowed citizens to sue government agencies that regulate mining.

SMCRA also created the Office of Surface Mining. This agency is part of the Department of the Interior. Its job is to make rules, fund state efforts to regulate and reclaim mines, and make sure state programs are consistent.

New Rules and Coal Supply Chains

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has received comments about coal supply chains. The American Coal Council(ACC) confirms that coal supply chains are heavily regulated. This happens at local, state, and federal levels.

Betsy Monseu, CEO of ACC, said that changes to rules, confusing rules, and uncertain rules affect businesses. She noted, "There are real consequences to people, their livelihoods, and their families." Even though coal mining causes more environmental problems, the EPA has started to see benefits from coal ash.

In 2020, the EPA stated, "Coal ash can be used to make new products, like wallboard or concrete." Because coal ash has many useful properties, businesses in construction, agriculture, and manufacturing use it instead of other materials. The ACC has been asking the EPA to consider using coal combustion residuals (CCR). The ACC says CCRs are good for the environment.

Even though the EPA has studied CCR and found it beneficial, no action has been taken. For CCR to be recognized as a good solution, the EPA must check it against four rules:

- The CCR must provide a useful benefit.

- The CCR must replace a new material. This saves natural resources that would otherwise need to be dug up.

- The use of CCRs must meet product standards or design standards. If no standards exist, CCR should not be used in too large amounts.

- If CCR is used on land without being sealed, and it's 12,400 tons or more in non-road areas, the user must show and keep records. These records must prove that environmental releases (like to water, soil, and air) are similar to or lower than those from similar products made without CCR. Or, they must show that releases will be at or below safe levels for people and nature.

Groups Working for Change

The idea of justice has often been looked at through the theories of John Rawls. Justice theory has focused on the rules for how goods should be shared in a society. The main arguments of the environmental justice movement were about patterns that broke these sharing rules. Several modern thinkers have developed broader ideas of justice.

The study of justice theory, when applied to environmental justice, has mostly focused on "maldistribution." This means that poor communities, Native American communities, and communities of color often suffer more from environmental damage. They also get less environmental protection.

Environmental justice has been seen as a movement that recognized how environmental damage and toxic pollution affect poor people and people of color more. It has also been noted that the race and social class of the groups involved affect their chances of success in making changes. Environmental justice groups were local, community-based organizations. They combined environmentalism with issues of race and class equality. These groups organized against the greater health dangers that mountain communities faced from things like acid mine drainage (polluted water from mines).

Save Our Cumberland Mountains

Save Our Cumberland Mountains (SOCM, pronounced "sock 'em") was started when thirteen people from Tennessee coalfields asked their state government to make coal landowners pay fair taxes. SOCM grew into a very important community organization in the region. It later led a big campaign against employers who replaced their permanent workers with temporary ones.

J.W. Bradley was the president of SOCM for its first five years. He had worked in deep mines and spoke out against what he called the "evils of strip mining." He believed in using lawsuits to bring about change. In 1974, SOCM created the East Tennessee Research Corporation as a public interest law firm. By 1976, SOCM was trying to ban strip mining and targeting specific strip mining operations.

An attorney who worked with SOCM in the 1970s wrote that very few people of color were involved with SOCM early on. He points out the importance of regional groups like the Highlander Research and Education Center. These groups "seek to bring together diverse communities to share their knowledge about the inner dynamics of environmental justice issues."

Mountain Justice

Mountain Justice started in 2005. It was a summer-long effort to stop mountaintop removal (MTM). The group began after a 2004 mining accident in Virginia. A three-year-old child was killed when a large rock rolled off an MTM site above his home.

The first Mountain Justice meeting happened in Knoxville, Tennessee. Activists from Coal River Mountain Watch (CRMW), the Sierra Club, Appalachian Voices, and Katuah Earth First (KEF!) attended. Their mission statement includes a promise to use non-violence.

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |