Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

|

|

|---|---|

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1823

|

|

| Born | 15 April 1772 Étampes, France

|

| Died | 19 June 1844 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | French |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history |

| Institutions | Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle |

| Influences | M. J. Brisson, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Lorenz Oken, Georges Cuvier |

| Influenced | Robert Edmond Grant |

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (born April 15, 1772 – died June 19, 1844) was a French naturalist. He believed that all animals are built on a similar basic plan. He worked with Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and supported Lamarck's ideas about how living things change over time.

Geoffroy thought there was a deep connection in how all living things are designed. He gathered evidence for his ideas by studying the bodies of different animals (comparative anatomy), old fossils (paleontology), and how animals develop before birth (embryology). He is seen as an early thinker in the field of evo-devo, which looks at how changes in development can lead to evolution.

Contents

Early Life and Career Beginnings

Geoffroy was born in Étampes, France. He studied natural philosophy in Paris. He also attended lectures at famous institutions like the College de France and the Jardin des Plantes.

In 1793, he became an assistant at the cabinet of natural history. Soon after, he was appointed one of the twelve professors at the new Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. He was given the job of teaching zoology, which is the study of animals. In the same year, he helped create a menagerie (a collection of wild animals) at the museum.

In 1794, Geoffroy started writing to Georges Cuvier, another important naturalist. Cuvier soon joined Geoffroy at the Museum. The two friends wrote several papers together. One of these papers, about how to classify mammals, introduced the idea that different animal features are related to each other. In 1795, Geoffroy wrote a paper where he first shared his idea about the "unity of organic composition." This means he believed nature uses one basic building plan for all living things, even if the details change.

Adventures and Discoveries

In 1798, Geoffroy joined Napoleon's big scientific trip to Egypt. He was part of the natural history and physics team. Many scientists and artists went on this trip. When the British took over Alexandria in 1801, they wanted to take the expedition's collections. Geoffroy bravely stood up to them. He said that if they took the collections, history would remember that he had also "burnt a library in Alexandria," comparing it to the ancient Library of Alexandria.

Geoffroy returned to Paris in early 1802. He became a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1807. The next year, Napoleon asked him to visit museums in Portugal. His goal was to bring collections from Portugal back to France. Despite strong opposition from the British, he succeeded in getting these collections for his country.

Later Career and Big Ideas

In 1809, Geoffroy became a professor of zoology at the faculty of sciences in Paris. From then on, he focused more on studying animal anatomy. In 1818, he published the first part of his famous book, Philosophie anatomique (Anatomical Philosophy). In the second part, published in 1822, he explained how birth defects (like having extra limbs) could happen. He thought they were caused by problems during development or by similar parts attracting each other.

Geoffroy's friend, Robert Edmond Grant, shared his ideas about the "unity of plan" in animals. Grant studied marine invertebrates in Scotland. He even had Charles Darwin as a student for a while. Grant successfully found the pancreas (an organ) in molluscs (like snails and clams).

The Great Debate: Geoffroy vs. Cuvier

In 1830, Geoffroy tried to apply his ideas about the "unity of animal composition" to animals without backbones (invertebrates). This led to a big argument with his former friend, Cuvier. This argument is known as the Cuvier–Geoffroy debate.

Geoffroy believed that all animals are made of the same basic parts, in the same number, and connected in the same way. He thought that homologous parts – parts that are similar in different animals because they come from a common plan – always stay in the same order, even if their shape and size change. He also believed that if one organ grew too much, another part would grow less. He thought that nature doesn't make sudden big changes. Even if an organ isn't very useful in one species, it might be kept as a small, leftover part (a rudiment) if it was important in other related species. This showed him that the general plan of creation stayed the same. He felt that living things had changed over time due to life conditions, but he didn't think existing species were still changing.

Cuvier, on the other hand, focused on observing facts. He believed that animal organs worked together in harmony. But he strongly believed that species never changed. He thought each species was created perfectly for its environment, with each organ designed for a specific job. Geoffroy thought Cuvier was confusing the cause with the effect.

In 1836, Geoffroy created the term phocomelia, which describes a birth defect where limbs are very short or missing.

In July 1840, Geoffroy became blind. A few months later, he had a stroke. His health slowly got worse. He retired from his teaching job at the museum in 1841. His son, Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, took over his position. Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire passed away in 1844.

Geoffroy's Theories on Change

Geoffroy was a deist. This means he believed in a God who created the universe, but then let it run by natural laws without direct interference. This idea was common during the Enlightenment. It meant he didn't believe in miracles or that the Bible was literally true. These beliefs fit well with his scientific ideas about how living things change.

Geoffroy's theory was not about all living things coming from one common ancestor. Instead, he thought that the environment could directly cause big changes in living things. This idea is sometimes called 'Geoffroyism'. It's different from what Lamarck believed. Lamarck thought that changes in an animal's habits caused it to change. Today, scientists don't believe that the environment directly causes big, inherited changes in the way Geoffroy thought.

Geoffroy also believed in "saltational evolution." This means he thought that big, sudden changes (like "monstrosities") could lead to new species appearing very quickly. For example, in 1831, he wondered if birds could have come from reptiles through a sudden, big change in their development. He wrote that environmental pressures could cause these sudden transformations to create new species instantly. Later, in 1864, another scientist named Albert von Kölliker brought back Geoffroy's idea that evolution happens in big steps.

Geoffroy also noticed that the back (dorsal) and front (ventral) structures in arthropods (like insects and spiders) seemed to be opposite to those in mammals. He suggested an "inversion hypothesis," meaning that these body plans were somehow flipped. This idea was criticized and rejected at the time. However, some modern scientists studying how embryos develop have recently looked at this idea again.

Animals Named After Geoffroy

Many animals have been named in honor of Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire:

- The Geoffroy's cat (Leopardus geoffroyi)

- Two species of South American turtle: Phrynops geoffroanus and Phrynops hilarii

- Geoffroy's spider monkey

- Geoffroy's bat

- Geoffroy's tamarin

- The Catfish Corydoras geoffroy

There is also a street in Paris, Rue Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, near the Jardin des Plantes and the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, named after him.

Works

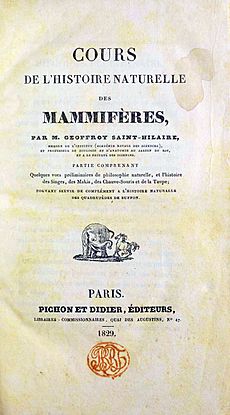

- Cours de l'histoire naturelle des mammifères (Course on the Natural History of Mammals), 1829

See also

In Spanish: Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire para niños

In Spanish: Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire para niños

- Cuvier–Geoffroy debate

Images for kids

-

Cartoon of Geoffroy as an ape, with Cuvier in the background, by Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Grandville, 1842