First English Civil War, 1643 facts for kids

1643 was a very important year during the First English Civil War. This war was fought between King Charles I and the Parliament. By the end of 1643, the war took a big turn. The King made a peace deal with Irish rebels on September 15. This made almost everyone in Protestant England angry and united them against him. Just ten days later, Parliament in Westminster made a promise called the Solemn League and Covenant. This agreement brought Scotland into the war on Parliament's side.

Contents

Winter Battles of 1642–1643

During the winter of 1642–1643, the King's army, led by Essex, stayed quiet near Windsor. Meanwhile, King Charles slowly made his position stronger around Oxford. Oxford became a main base, and other towns like Reading and Marlborough were fortified. This created a strong defensive circle for the King.

In the North and West, fighting continued through the winter. In December 1642, Newcastle, a Royalist commander, moved south. He defeated Sir John Hotham, a Parliament leader in the North. Newcastle then joined other Royalists in York. This forced Lord Fairfax and his son Sir Thomas Fairfax, who fought for Parliament, to retreat.

Newcastle then tried to capture important towns in the West Riding, like Leeds and Bradford. But the people there fought back strongly. Sir Thomas Fairfax helped them with his cavalry. By late January 1643, Newcastle gave up trying to take these towns.

Newcastle continued to move south, gaining ground for the King. He reached Newark-on-Trent, connecting with Royalists in other counties. This prepared the way for the Queen's arrival with more supplies from overseas.

In the West, Royalist leaders like Hopton drove Parliament's forces out of Cornwall. They then moved into Devonshire in November 1642. A Parliament army, led by the Earl of Stamford, came from South Wales to fight Hopton. Hopton had to go back to Cornwall. But with more local fighters, he won a big victory at the Battle of Bradock Down on January 19, 1643.

Around the same time, Royalists from South Wales joined the King at Oxford. The King's fortified area grew when they captured Cirencester on February 2. Only Gloucester and Bristol remained as important Parliament strongholds in the West.

In the Midlands, Parliament had a victory at the Battle of Nantwich on January 28. But Royalists still grew stronger, connecting with their friends at Newark. A new Royalist army formed near Chester. Parliament's commanders, Sir William Brereton and Sir John Gell, struggled to hold their ground.

Lord Brooke, a Parliament commander, was killed on March 2 while attacking Lichfield Cathedral. Even though the cathedral was captured, Gell and Brereton faced tough fighting at the Battle of Hopton Heath on March 19. Prince Rupert, a Royalist leader, then quickly recaptured Lichfield Cathedral. He was soon called back to Oxford for the main war effort.

Parliament's situation looked difficult in January. Royalist victories and new taxes made their supporters lose hope. There were even troubles in London. Some Parliament supporters wanted help from Scotland. Others wanted peace at any cost.

But things soon got better for Parliament. Stamford in the West and Brereton and Gell in the Midlands kept fighting. Newcastle failed to take the West Riding. Sir William Waller, another Parliament commander, cleared areas in Hampshire and Wiltshire. He then entered Gloucestershire in March, winning a battle at Highnam on March 24. This secured Bristol and Gloucester for Parliament.

Also, some of King Charles's secret plans were discovered. This made people who were unsure about the war decide to support Parliament again. Peace talks, known as the "Treaty of Oxford," ended in April without any real progress.

Around this time, Parliament also created "associations" of counties. These groups worked together for defense. The strongest was the Eastern Association, based in Cambridge. This group was greatly helped by Colonel Oliver Cromwell.

War Plans for 1643

The King's plan for the next part of the war was quite detailed. His main army near Oxford would keep Essex's forces busy. At the same time, Royalist armies in Yorkshire and the West would fight their way towards London. The goal was for all three armies to meet in London. They would cut off Parliament's supplies and money, forcing them to give up. This plan depended on Essex's army staying stuck in the Thames valley.

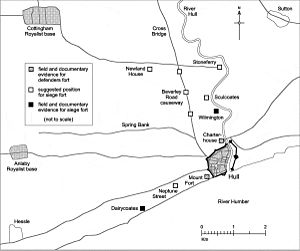

However, the King's plan faced problems because of local feelings. Even after the Queen arrived with more troops, Newcastle had to stay in the North. This was because of strong resistance in Lancashire and the West Riding. Also, the port of Hull, held by the Fairfaxes, was a big threat that Royalists in Yorkshire didn't want to ignore.

Hopton's advance in the West also faced difficulties. His forces were stopped at the Battle of Sourton Down on April 25. On the same day, Waller captured Hereford. Essex had already begun attacking Reading, an important fortress near Oxford. Reading surrendered to Essex on April 26. So, the start of the King's plan was delayed.

Hopton's Victories in the West

Things improved for the Royalists in May. The Queen's convoy arrived at Woodstock on May 13, 1643. Stamford's army, which had entered Cornwall again, was attacked and almost completely destroyed by Hopton at the Battle of Stratton on May 16. This great victory was largely due to Sir Bevil Grenville and his Cornish soldiers. Even though they were outnumbered, they fought bravely and captured many of the enemy. Devon was quickly taken over by the victors.

Essex's army, after capturing Reading, couldn't do much more due to lack of supplies. A Royalist force moved to Salisbury to meet their friends in Devon. Waller, the only Parliament commander left in the West, had to give up his gains to stop Hopton.

In early June, Hertford and Hopton joined forces and moved towards Bath, where Waller's army was. They tried to surround Waller, but he acted very skillfully. After several days of movements and small fights, the Royalists attacked Waller's strong position on Lansdown Hill on July 5. The battle of Lansdown was a victory for the Royalists, but they lost many soldiers, including Sir Bevil Grenville.

After the battle, Waller's men retreated to Bath. The Royalists, though victorious, had suffered greatly. Hopton was badly injured by an explosion. The Royalists then moved east to Devizes, with Waller following closely.

On July 10, Sir William Waller took a position on Roundway Down, overlooking Devizes. He captured Royalist supplies. On July 11, he surrounded Hopton's soldiers in Devizes. The Royalist cavalry rode away to get help. But the Cornish soldiers, led by Hopton from his bed, fought very bravely. On July 13, Prince Maurice's cavalry arrived from Oxford, saving their comrades.

Waller's army fought hard, but the Royalist attack from both sides destroyed his army. Soon after, Prince Rupert arrived with more Royalist forces. They moved west, aiming for Bristol, the second largest port. On July 26, Bristol was captured. Waller, with the remains of his army, could not stop them. This victory greatly helped the Royalist cause in the West.

Adwalton Moor Battle

Meanwhile, Newcastle started fighting the clothing towns again, this time with success. The Fairfaxes had been fighting in the West Riding since January 1643. They were too weak against Newcastle's growing forces. An attempt to send help from other Parliament forces failed because local interests prevented them from working together.

Around the same time, Hull itself almost fell due to disloyalty from its governor, Sir John Hotham, and his son. They were later arrested by the citizens and faced serious consequences. More serious was a large Royalist plan discovered in Parliament itself. Several important people were arrested for being involved.

The safety of Hull did not help the West Riding towns. The Fairfaxes suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Adwalton Moor near Bradford on June 30. After this, they escaped to Hull and prepared its defense. The West Riding then had to surrender.

The Queen, with more supplies and a small army, joined her husband in Oxford on July 14. But Newcastle was not yet ready to move his army towards London. His Yorkshire troops would not march while Hull was still held by Parliament. This created a strong barrier between the Royalist army in the North and London.

Even though there were peace protests in London and disagreements among Parliament's leaders, the defeats at Roundway Down and Adwalton Moor were not the end. A new and very important force had emerged: the Eastern Association.

Cromwell and the Eastern Association

The Eastern Association had already helped in the siege of Reading and sent troops to other areas. From the very beginning, Oliver Cromwell was its most important leader.

After the Battle of Edgehill, Cromwell said that Parliament needed soldiers with strong spirits, not just "old decayed serving-men." In January 1643, he went to his home county to find "men as had the fear of God before them." These men, once found, were willing to train hard and follow strict rules. This was something other soldiers, fighting only for honor or money, could not do. The results were quickly seen.

As early as May 13, Cromwell's cavalry regiment, made up of skilled horsemen from the eastern counties, showed how good they were in a small fight near Grantham. In the fighting in Lincolnshire during June and July, Cromwell's Puritan troopers were known for their long and fast marches. On July 28, Cromwell led his regiment and other cavalry to a brilliant victory at Gainsborough. They completely defeated the Royalist cavalry and killed their general, Charles Cavendish.

Meanwhile, Essex's army had been inactive. After taking Reading, many soldiers became sick. On June 18, Parliament's cavalry was defeated, and John Hampden, an important Parliament leader, was badly wounded at Chalgrove Field. When Essex finally got more soldiers and moved towards Oxford, his men were not ready to fight.

Essex retreated to Bedfordshire in July, unable to stop the Queen's convoys. This allowed the Oxford army to help in other parts of the country. Waller complained that Essex had not supported him before the defeat at Roundway Down. However, few people called for Essex to be removed. He would soon have a chance to prove himself in a major campaign.

The Royalist armies had briefly joined forces to defeat Waller at Bristol. But their unity did not last long. Hopton's men wanted to capture Plymouth, just as Newcastle's men wanted Hull. They would not march on London until these threats to their homes were gone. Also, there were disagreements among the Royalist generals.

So, the original plan was changed. The main Royalist army would fight in the center. Hopton's (now Maurice's) army would be on the right, and Newcastle's on the left, moving towards London. While waiting for Hull and Plymouth to fall, King Charles decided to attack Gloucester, Parliament's last big fortress in the West.

Siege and Relief of Gloucester

This decision quickly led to a major event. The Earl of Manchester (with Cromwell as his second-in-command) was put in charge of the Eastern Association forces against Newcastle. Waller was given a new army to fight Hopton and Maurice. But the job of saving Gloucester from the King's army fell to Essex.

Essex's army was greatly strengthened in late August. New soldiers were forced to join, and recruiting for Waller's army was stopped. London sent six regiments of its trained bands (citizen soldiers) to the front. Shops were closed so everyone could help in what was seen as a very important fight.

On August 26, 1643, Essex's army began its march. They moved bravely towards Gloucester, even though they lacked food and rest, and Rupert's cavalry attacked their sides. On September 5, just as Gloucester was about to run out of supplies, the siege of Gloucester was suddenly lifted. The Royalists moved away because Essex had reached Cheltenham, and the danger was over. The armies were now free to move and face each other.

There followed a series of clever movements in the Severn and Avon valleys. In the end, Parliament's army got a head start on its way back home.

But the Royalist cavalry under Rupert, followed quickly by King Charles and the main army, tried very hard to cut off Essex at Newbury. After a small fight on September 18, they succeeded. On September 19, the Royalist army was ready, facing west. Essex's men knew they would have to fight their way through.

First Battle of Newbury

The battlefield was full of hedges, except for some open areas. Essex's army could not form a straight battle line. Each group of soldiers joined the fight as they arrived.

On Parliament's left side, their attack was successful. They captured ground even with Royalist counter-attacks. Here, Viscount Falkland, an important Royalist, was killed. On the main road, Essex could not get his men into the open, but his soldiers bravely pushed back the Royalist cavalry.

On the far right of Parliament's army, in an open area, something famous happened. Two London regiments, new to war, faced a very tough test. Rupert and the Royalist cavalry charged their squares of pikemen again and again. Between charges, Royalist cannons tried to break their formation. But the Londoners held their ground. They only retreated slowly and in perfect order when the Royalist foot soldiers advanced.

Essex's army had fought its hardest but could not break the Royalist line. However, the Royalists had suffered many losses. They were also very impressed by the bravery of Parliament's soldiers. So, they were happy to give up the disputed road and retreat into Newbury. Essex then continued his march. He reached Reading on September 22, 1643. This ended the First Battle of Newbury, a very dramatic event in English history.

Hull and Winceby Victories

Meanwhile, the siege of Hull had begun. The Eastern Association forces under Manchester quickly moved into Lincolnshire. Their foot soldiers attacked Lynn (which surrendered on September 16, 1643). Their cavalry rode north to help the Fairfaxes. Luckily, Hull could still get supplies by sea.

On September 18, some cavalry from Hull crossed to Barton. The rest, led by Sir Thomas Fairfax, went by sea a few days later. They all joined Cromwell near Spilsby. In return, Lord Fairfax, who stayed in Hull, received more soldiers and supplies from the Eastern Association.

On October 11, Cromwell and Fairfax won a brilliant cavalry battle at Battle of Winceby. They chased the Royalist cavalry all the way to Newark. On the same day, Newcastle's army around Hull, tired from the long siege, was attacked by the Hull defenders. They were so badly beaten that the siege was given up the next day. Later, Manchester recaptured Lincoln and Gainsborough. So, Lincolnshire, which Newcastle had almost controlled, became part of the Eastern Association.

After the intense fighting at Newbury, the war slowed down in other areas. The London regiments went home, leaving Essex too weak to hold Reading. The Royalists took Reading back on October 3. The Londoners then offered to serve again. They helped in a small campaign around Newport Pagnell, where Rupert was trying to build a fort to threaten the Eastern Association.

Essex stopped this plan, but his London regiments went home again. Sir William Waller's new army in Hampshire failed badly in an attack on Basing House on November 7. The London-trained bands left the fight. Shortly after, on December 9, Arundel surrendered to a force led by Lord Hopton.

The Irish Truce and the Solemn League and Covenant

Politically, these months were a turning point in the war. In Ireland, the King's representative made a truce with the Irish rebels on September 15, 1643. King Charles's main goal was to bring his army from Ireland to fight in England. But many people believed that Irish soldiers, who were Catholic, would soon arrive. This action united almost every Protestant in England against the King. It also brought the strong army of Presbyterian Scotland into the English conflict.

However, King Charles still tried to use secret plans to keep Scotland from joining the war. He ignored the advice of Montrose, one of his most loyal leaders, who wanted to keep the Scots busy at home. Just ten days after the "Irish Cessation" (truce), Parliament in Westminster swore to the Solemn League and Covenant. This meant the decision was made: Scotland would join Parliament.

It is true that this agreement, which seemed to bring a strict religious government, made some groups in Parliament, called "Independents," cautious. They secretly talked with King Charles about freedom of religion. But they soon found out that the King was only using them to try and betray some small Parliament strongholds. For now, all groups agreed to interpret the Covenant in a way that suited them. By early 1644, Parliament was so united that even the death of John Pym, an important leader, on December 8, 1643, did not stop their resolve to continue the fight.

The troops from Ireland, gained at the cost of a huge political mistake, turned out not to be very reliable. Those serving in Hopton's army were causing trouble and seemed influenced by the rebellious mood in England. When Waller's Londoners surprised and defeated a Royalist group at Alton on December 13, 1643, half of the captured soldiers joined Parliament's side.