First Intermediate Period of Egypt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

First Intermediate Period of Egypt

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2181 BC–c. 2055 BC | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||

| Common languages | Ancient Egyptian | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||

|

• c. 2181 BC

|

Menkare (first) | ||||||||

|

• c. 2069 BC – c. 2061 BC

|

Intef III (last; Theban) Merykare (last; Herakleopolitan) |

||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Began

|

c. 2181 BC | ||||||||

|

• Ended

|

c. 2055 BC | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | Egypt | ||||||||

The First Intermediate Period was a time in ancient Egyptian history that lasted about 125 years, from around 2181 BC to 2055 BC. It came right after the powerful Old Kingdom. This period included the Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and part of the Eleventh Dynasties.

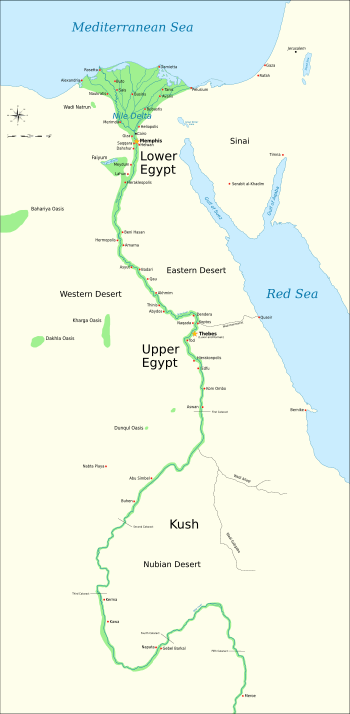

During this time, Egypt was split into two main areas of power. One was in Lower Egypt at a city called Heracleopolis. The other was in Upper Egypt at Thebes. It's thought that there was a lot of political trouble. Temples might have been robbed, artwork damaged, and statues of kings broken. Eventually, the two kingdoms fought each other. The kings from Thebes won, taking control of the north. This reunited Egypt under one ruler, Mentuhotep II. This event marked the start of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

Contents

History of the First Intermediate Period

Why the Old Kingdom Ended

Many ancient writings describe the end of the Old Kingdom as a time of great confusion. Several things likely caused its downfall. One big reason was the very long rule of Pepi II. He was the last major pharaoh of the 6th Dynasty. He ruled from when he was a child until he was very old, possibly over 90. Because he lived so long, many of his chosen heirs died before him. This created big problems for who would rule next.

Another issue was that local governors, called nomarchs, became very powerful. Towards the end of the Old Kingdom, these positions became hereditary. This meant families kept control of their provinces for generations. As nomarchs gained more power, they became more independent from the pharaoh. They built their own tombs and even raised their own armies. This led to fights and wars between different provinces.

Some historians also suggest that low levels of the Nile flood might have played a role. This could have been caused by a drier climate. Lower floods meant less water for crops, which could lead to famine across Egypt. However, experts still debate how much this affected the kingdom's collapse.

The Seventh and Eighth Dynasties

Not much is known about the rulers of the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties. A historian named Manetho wrote that 70 kings ruled for 70 days during this time. This is probably an exaggeration. It was meant to show how disorganized the kingship was.

The Seventh Dynasty might have been a group of powerful officials from the Sixth Dynasty. They were based in Memphis and tried to keep control of the country. The Eighth Dynasty rulers also ruled from Memphis. They claimed to be related to the earlier Sixth Dynasty kings.

Because there is so little evidence, we don't know much about these two dynasties. However, some artifacts have been found. These include scarabs linked to King Neferkare II of the Seventh Dynasty. A small pyramid believed to be built by King Ibi of the Eighth Dynasty has also been found at Saqqara.

Rise of the Heracleopolitan Kings

After the little-known Seventh and Eighth Dynasty kings, a new group of rulers appeared. They were based in Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt. These kings formed the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties.

The first king of the Ninth Dynasty was Akhthoes, also known as Akhtoy. He is often described as a cruel ruler. One story says he caused much harm to Egypt. He was said to have gone mad and was eventually killed by a crocodile. This might be a made-up story, but Akhthoes is listed as a king in ancient records.

A powerful family of nomarchs grew in Siut (or Asyut). This was a rich province in the south of the Heracleopolitan kingdom. These local princes were warriors and had strong ties with the Heracleopolitan kings. Inscriptions in their tombs tell us about the politics of their time. They describe the Siut nomarchs digging canals, lowering taxation, and having good harvests. They also raised cattle and kept an army and navy. Siut acted as a protective zone between the northern and southern rulers. Its princes often faced attacks from the Theban kings.

Ankhtifi, a Powerful Warlord

In the south, powerful local leaders, called warlords, took control. The most famous of these was Ankhtifi. His tomb was found in 1928 at Mo’alla, south of Luxor. He was a nomarch of the area around Hierakonpolis. He then expanded his power south and took over another region near Edfu. He tried to move north to conquer Thebes, but the Thebans refused to fight him directly.

Ankhtifi's tomb is beautifully decorated. It contains his life story, where he says he saved Egypt from hunger and famine. He claimed, "I gave bread to the hungry and did not allow anyone to die." Many rulers made similar claims, so it's hard to know how bad the situation truly was. But it's clear that Ankhtifi was a powerful ruler in his region. He didn't seem to answer to any higher authority. This shows that Egypt's unity had broken down.

Rise of the Theban Kings

Around the same time the Heracleopolitan kingdom was founded, another group of kings rose in Upper Egypt. These were the Theban kings, who formed the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties.

These kings are believed to be descendants of Intef. He was the nomarch of Thebes and was known as the "keeper of the Door of the South." He helped organize Upper Egypt into an independent ruling area. However, he didn't claim the title of king himself. His successors in the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties would later do so.

One of them, Intef II, began attacking the north, especially the city of Abydos. By about 2060 BC, Intef II had defeated the governor of Nekhen. This allowed him to expand further south towards Elephantine. His successor, Intef III, finished conquering Abydos. He then moved into Middle Egypt against the Heracleopolitan kings.

The first three kings of the Eleventh Dynasty were all named Intef. They were also the last three kings of the First Intermediate Period. They were followed by a line of kings all named Mentuhotep. Mentuhotep II, also known as Nebhepetra, finally defeated the Heracleopolitan kings around 2033 BC. He reunited the country, continuing the Eleventh Dynasty and starting the Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

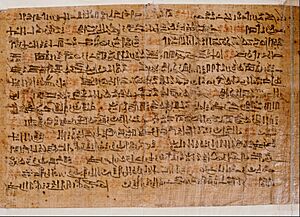

The Ipuwer Papyrus

During the First Intermediate Period, new kinds of writings began to appear. One important text is the Ipuwer Papyrus. It's often called the Lamentations or Admonitions of Ipuwer. Even though experts don't think it was written exactly during this period, it might describe the First Intermediate Period. It talks about a decline in international relations and a general increase in poverty in Egypt.

Art and Architecture of the First Intermediate Period

During the First Intermediate Period, Egypt was split into two main areas. One was centered in Memphis, and the other in Thebes. The Memphite kings, though not very powerful, tried to keep the artistic styles of the Old Kingdom. This was a way for them to hold onto the memory of the Old Kingdom's glory.

The Theban kings, however, were far from Memphis. They had to create their own style of art. This "Pre-Unification Theban Style" helped them show their power and bring order to their kingdom through art.

Not much is known about the art style from the North (Heracleopolis). This is because there isn't much information about the Heracleopolitan kings on their monuments. But we know a lot about the Pre-Unification Theban Style. The Theban kings of the early Eleventh Dynasty used art to show that their rule was rightful. They set up many royal workshops, creating a unique Upper Egyptian art style. This style was different from the older Old Kingdom art rules.

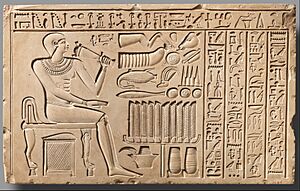

The art from this period often used either high raised relief or deep sunk relief with carved details. Figures in these artworks had narrow shoulders and a high, small back. Their limbs were rounded, and male figures often lacked detailed muscles. Sometimes, males were shown with rolls of fat, a style that started in the Old Kingdom to show older men.

Faces in this style had large eyes, outlined with a band of relief that looked like eye paint. This line usually went back to the ear. The eyebrow above the eye was mostly flat. Noses were broad and deeply carved. Ears were large and slanted.

An example of this Theban art is the Stela of the Gatekeeper Maati. This limestone slab is from the time of Mentuhotep II, around 2051-2030 BCE. In this stela, Maati sits at an offering table. He holds a jar of sacred oils. The text around him mentions others from his life, like the treasurer Bebi and the ancestor of the ruling Intef family. This shows the strong connections between rulers and their followers in Theban society during this period.

Statues from this time also show strong facial features and rounded limbs. An example is the Limestone Statue of the Steward Mery, from the 11th Dynasty.

The Limestone Relief of High Official Tjetji has 14 lines of text at the top. This text tells about Tjetji's life. Five vertical columns on the right describe a special offering formula used during the First Intermediate Period. Tjetji faces right, with two smaller male figures on his left. These are likely his official staff. Tjetji is shown as an older official with a noticeable chest and rolls of fat on his body. He wears a kilt that reaches his calves. The officials on the left are younger and wear shorter kilts, showing they are less mature.

The building projects of the Heracleopolitan kings in the North were very few. Only one pyramid is thought to belong to King Merikare (2065–2045 BC). It is believed to be somewhere at Saqqara. Private tombs built during this time were much smaller and less grand than Old Kingdom monuments. They still had scenes of servants preparing food for the dead and traditional offering scenes, similar to Old Kingdom tombs. However, they were simpler and not as well made.

Wooden rectangular coffins were still used, but their decorations became more detailed under the Heracleopolitan kings. New Coffin Texts were painted inside. These texts provided spells and maps for the deceased to use in the afterlife.

Art from the Theban Period shows that artists interpreted traditional scenes in new ways. They used bright colors in their paintings. They also changed and sometimes distorted the proportions of the human body. This unique style was very clear in the rectangular slab stelae found in tombs at Naga el-Deir.

For royal buildings, the early Eleventh Dynasty Theban kings built rock-cut tombs called saff tombs. These were located at El-Tarif on the west bank of the Nile. This new style of tomb had a large courtyard with a rock-cut colonnade at the far wall. Rooms were carved into the walls facing the central courtyard where the dead were buried. This allowed multiple people to be buried in one tomb. The burial chambers were often undecorated, possibly because the Theban kingdom lacked skilled artists at the time.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |