Fluxus facts for kids

Fluxus was a group of artists, musicians, and poets from the 1960s and 1970s. They came from all over the world and loved to experiment with art. Instead of focusing on a perfect finished artwork, they cared more about the process of making it.

Fluxus artists were known for creating new kinds of art. This included "intermedia" (a mix of different art forms), "conceptual art" (where the idea is more important than the art object), and "video art." Many people, like art critic Harry Ruhé, called Fluxus "the most radical and experimental art movement of the sixties."

They created "events" which were like short performances. They also made noise music, poetry, visual art, and even worked on ideas for cities and designs. Many Fluxus artists didn't like art being sold for money or being too "fancy." They were influenced by composer John Cage, who believed art should be an interaction between the artist and the audience. Another big influence was Marcel Duchamp, a French artist known for his "readymades"—ordinary objects he called art, like a toilet. George Maciunas is seen as the founder of Fluxus. He came up with the name in 1961 for a magazine he wanted to start.

Many famous artists were part of Fluxus, including Joseph Beuys, Yoko Ono, and Nam June Paik. They were a diverse group who influenced each other and were often friends. They had new ideas about art and its place in society. Maciunas wrote a manifesto, but Fluxus was more like a loose community than a strict movement. Festivals in cities like Wiesbaden and New York helped bring them together. Fluxus played a big part in changing what people thought art could be. Some artists even called Fluxus a "laboratory" because it was all about trying new things.

Contents

How Fluxus Began (Late 1950s to 1965)

Early Ideas

The ideas behind Fluxus came from composer John Cage. He taught classes in New York City from 1957 to 1959. In these classes, he explored how chance and randomness could be part of art. He used music scores that could be performed in endless ways. Some future Fluxus artists, like La Monte Young and George Brecht, took his classes.

Another key influence was Marcel Duchamp. He created "anti-art" around 1913 with his "readymades." These were everyday objects, like a urinal, that he simply called art. This challenged the idea that art had to be beautiful or made with special skills. Duchamp and his friends formed a "Dada" group in New York. Their ideas greatly influenced Fluxus and "conceptual art."

First Fluxus Events

Before Fluxus officially started, there were other experimental art events. In 1961, Yoko Ono and La Monte Young organized concerts in New York. In 1963, George Brecht and Robert Watts held the "Yam" festival, which involved mail art. Also, in 1960, Nam June Paik performed a famous piece in Germany where he cut off John Cage's tie!

As one of the founders, Dick Higgins, said, Fluxus didn't start from scratch. It was like it "started in the middle" with existing experimental works.

George Maciunas, a graphic designer, helped La Monte Young with a magazine layout. This led to Maciunas getting involved with these artists. He later moved to Germany. From there, he stayed in touch with the New York artists and others he met in Europe. He planned a new publication called "Fluxus."

From "Neo-Dada" to "Fluxus"

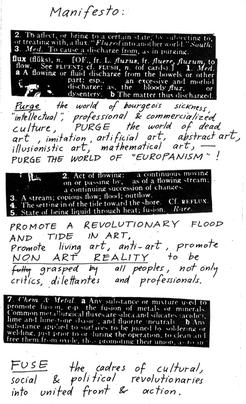

George Maciunas, who was from Lithuania, named the art produced by these artists "Fluxus." He wanted to bring together "cultural, social, and political revolutionaries." After moving to New York, he met the artists around John Cage. He opened a gallery for a short time, showing works by Yoko Ono and others.

In late 1961, Maciunas moved to Germany. On June 9, 1962, he organized a festival called Après Cage; Kleinen Sommerfest. There, he first used the term Fluxus (meaning 'to flow') in a brochure.

Maciunas first thought of Fluxus as "neo-dadaism" (new Dada). He wrote to Raoul Hausmann, an original Dada artist. Hausmann told him not to use "neo-dadaism" because "neo" meant nothing and "-ism" was old-fashioned. He suggested "Why not simply 'Fluxus'? It seems to me much better, because it's new."

At the festival, Maciunas gave a talk. He said Fluxus was against keeping everyday things out of art. He believed Fluxus would fight "traditional art" by using "anti-art and artistic banalities." He ended by saying, "Anti-art is life, is nature, is true reality—it is one and all."

European Festivals and Fluxkits

In 1962, Maciunas, Higgins, and Knowles went to Europe to promote their planned Fluxus publication. They held concerts with old musical instruments. With help from artists like Joseph Beuys and Wolf Vostell, Maciunas organized many "Fluxfests" across Western Europe.

These festivals, starting in Wiesbaden in September 1962, featured music by John Cage and others. They also included performances by Higgins, Knowles, and Nam June Paik. One performance, Piano Activities by Philip Corner, became famous. It involved destroying a piano, which shocked many people in Germany. It was even shown on German television!

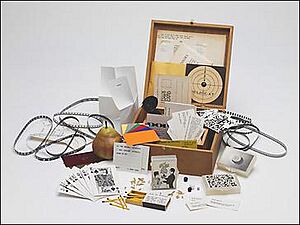

Maciunas also used his work connections to print cheap books and art by these artists. The first was Water Yam by George Brecht. It was a box of small cards with "event scores" (simple instructions for performances). These became known as Fluxkits. They were cheap, easy to make, and easy to share. Maciunas wanted them to be a growing library of modern performance art.

Maciunas wanted to design and pay for each edition himself, with the artists sharing the profits. Since many composers already had publishing deals, Fluxus moved more towards performance and visual art. For example, John Cage never published under the Fluxus name because of his existing contract.

Because Maciunas was colorblind, most Fluxus items were black and white.

New York and FluxShops

After his job ended, Maciunas returned to New York in September 1963. He started organizing street concerts and opened a new shop, the "Fluxhall," on Canal Street.

From April to May 1964, 12 concerts took place on Canal Street. Artists like Ben Vautier and Alison Knowles performed for free in the street. Maciunas took photos himself. These artists believed that concert halls and galleries were "mummifying" art. They preferred streets and homes. Maciunas saw a strong political message in this anti-establishment approach.

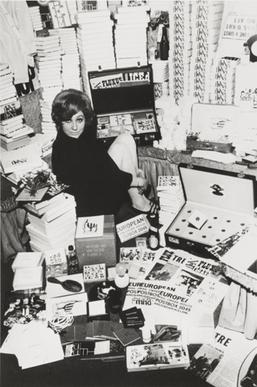

Maciunas also built a network to distribute the new art across Europe, California, and Japan. Shops and mail-order places opened in Amsterdam, Milan, and London. By 1965, the first big collection, Fluxus 1, was available. It was a manila envelope filled with works by artists like La Monte Young and Yoko Ono. Other items included altered playing cards, sensory boxes, and tin cans filled with poems about beans by Alison Knowles.

The Originale Protest

Back in New York, Maciunas reconnected with Henry Flynt. Flynt encouraged Fluxus to be more political. This led to a protest at the American premiere of Originale, a work by German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, on September 8, 1964.

Maciunas and Flynt called Stockhausen a "Cultural Imperialist." But other Fluxus members disagreed. So, some Fluxus artists, like Nam June Paik, crossed the picket line formed by others, like Ben Vautier. Dick Higgins joined the picket line, then went inside to perform. This caused a split in the group.

This event, organized by Charlotte Moorman, created bad feelings between Maciunas and her. Maciunas often told artists not to work with Moorman's annual festival and would even kick out those who did. This hostility continued even though Moorman kept supporting Fluxus art.

Fluxus in the Middle Years (1965–1978)

New Influences

Maciunas's strong political approach caused some early Fluxus members to leave. Jackson Mac Low resigned in 1963, and George Brecht left New York in 1965. Dick Higgins also had disagreements with Maciunas, partly because he started his own publishing company, the Something Else Press.

This opened the door for Japanese artists to have a bigger influence on Fluxus. Yoko Ono had been telling artists in Japan to look up Maciunas if they moved to New York. By 1965, artists like Shigeko Kubota and Takako Saito were making more thoughtful works for Fluxus.

In 1964, Yoko Ono, who was not always a follower of the Fluxus community, published her book Grapefruit. It contained "event scores" and other instructions for participatory art.

Here's an example from her book:

Imagine the clouds dripping.

Dig a hole in your garden to put them in.

Early Performance Art

On September 25, 1965, the FluxOrchestra performed at Carnegie Recital Hall in New York. La Monte Young conducted, and George Maciunas designed the poster. People folded copies of the program into paper airplanes and threw them during the show! The evening included performances by Yoko Ono, George Brecht, and many others.

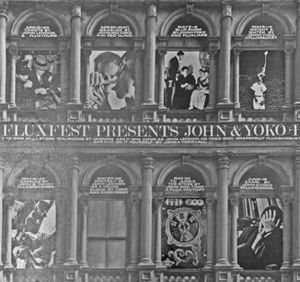

In 1969, Fluxus artist Joe Jones opened his JJ Music Store. He displayed his "drone music machines" in the window. Anyone could press buttons to play them. Jones also held small performances there, sometimes with Yoko Ono and John Lennon. From April to June 1970, Ono and Lennon (as the Plastic Ono Band) presented a series of Fluxus events there called GRAPEFRUIT FLUXBANQUET.

Blurring Art Boundaries

As Fluxus became more known, Maciunas wanted to sell more cheap art items. The Fluxkit (late 1964) was a collection of 3D works in a businessman's case, inspired by Duchamp. Soon, plans for Fluxus 2 were underway. It would include Flux films, altered matchboxes, plastic food, and even "FluxMedicine" (empty pill packages).

Maciunas believed in shared ownership. Many pieces from this time were anonymous or had their artists questioned. Maciunas also often changed artists' ideas before making the works. For example, Solid Plastic in Plastic Box, credited to Per Kirkeby, was originally a metal box with sawdust inside. Maciunas changed it to a solid plastic block in a plastic box.

Maciunas would buy many plastic boxes and ask artists to turn them into Fluxkits. Artists from around the world also sent items for works, like the small rocks in Robert Watts's Fluxatlas (1973).

Developing Performance Art

Larry Miller, who joined Fluxus in 1969, not only created his own works but also helped perform older Fluxus pieces. He organized many Fluxus events and collected a lot of information about its history. Thanks to Miller, Fluxus gained media attention, like the CNN coverage of the Off Limits exhibit in 1999.

Miller also helped create new versions of the Flux Labyrinth, a huge maze he first built with George Maciunas in Berlin in 1976.

Women in Fluxus

Women artists like Carolee Schneemann, Charlotte Moorman, Alison Knowles, and Yoko Ono were very important to Fluxus. They created works in different media, like Knowles's "Make a Salad" and "Make a Soup." They often explored themes related to the body, creating a strong female presence in the group.

Some women artists used their work to criticize how male-dominated society and even the art world were. However, Mieko Shiomi said that the best thing about Fluxus was that "there was no discrimination on the basis of nationality and gender. Fluxus was open to anyone who shared similar thoughts about art and life."

Dreaming of Communities

Some Fluxus artists wanted to create "Flux communes" to connect artists with society. The first was "La Cédille qui Sourit" (The Cedilla That Smiles) in France, started by Robert Filliou and George Brecht (1965–1968). It was a "Centre of Permanent Creation" that sold Fluxkits and had a "non-school" with no teachers or students.

In 1966, Maciunas and others took advantage of new laws to buy live/work spaces for artists in SoHo, New York. Maciunas wanted to create shared workshops, food co-ops, and theaters. He even planned a "FluxIsland" near Antigua, but the money never came through. These plans faced many financial problems and issues with New York authorities. In 1975, Maciunas was badly beaten by thugs sent by an unpaid contractor.

The End of an Era

Many people say Fluxus ended when its founder, George Maciunas, died in 1978 from cancer. His funeral was a typical Fluxus event, called "Fluxfeast and Wake," where people ate only black, white, or purple foods. Maciunas shared his thoughts on Fluxus in video interviews with artist Larry Miller.

Fluxus After 1978

In the late 1970s, Maciunas moved to Massachusetts. Art collector Jean Brown, who had a large collection of Dada and Surrealist art, became interested in Fluxus. Maciunas helped turn her home into an important center for Fluxus artists and scholars.

Three months before he died, Maciunas married Billie Hutching. They had a legal wedding and then a "Fluxwedding" in a friend's loft in New York, where they traded clothes. Maciunas died on May 9, 1978.

After Maciunas's death, there was a disagreement about whether Fluxus was over. Some collectors and curators said it was a historical movement that ended in 1978. But many artists believed Fluxus was still alive, based on its core ideas. Today, some refer to Fluxus in the past tense, while others use the present tense.

Some argue that Jon Hendricks, who manages a major Fluxus collection, has influenced the idea that Fluxus ended with Maciunas. He believes artists like Dick Higgins and Nam June Paik could no longer call themselves active Fluxus artists after 1978. However, the influence of Fluxus continues today in multi-media digital art performances. In 2011, a performance in San Francisco celebrated the 50th anniversary of Fluxus.

Others, like Hannah Higgins (daughter of Fluxus artists Alison Knowles and Dick Higgins), say that many artists continued to work within Fluxus after Maciunas's death. The internet helped a lively "post-Fluxus" community grow online. Younger artists continue to be inspired by Fluxus, staging events to honor it.

In 2018, the Los Angeles Philharmonic held a Fluxus Festival, showing that Fluxus performances still happen today.

What Influenced Fluxus

Maciunas said that the Gutai group from Japan was an early influence on Fluxus. Gutai artists believed art should be an "anti-academic" experience, focusing on the materials themselves. They also blurred the lines between fancy art and everyday things, which became a trademark of Fluxus.

In the 1950s, many people felt disappointed after World War II. This led to an interest in Buddhism and Zen, and a desire for more radical art. Ideas about decay and the problems with modern art came from Duchamp and Dada.

Fluxus challenged the idea of "representation" (art looking like something else) and instead focused on "simple presentation." This is similar to Japanese art, which often doesn't separate art from life. Fluxus artists also believed that "every man is an artist," as Joseph Beuys said. Their art was often "economic," using small, everyday objects made of paper and plastic. This connects to Japanese culture's appreciation for simple, frugal things and the idea of "shibumi," which values incompleteness and subtlety.

Fluxus Art Style

Fluxus encouraged a "do-it-yourself" approach. They valued simplicity over being complicated. Like Dada, Fluxus was against art being just for money and challenged the serious art world. However, Robert Filliou said Fluxus was different from Dada because it had more positive goals, like bringing people together.

Early Fluxus artists like Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, and Yoko Ono explored many art forms, from performance to poetry to film. They were against traditional art and professionalism. They focused on the artist's personality and actions rather than just the finished product. They staged "action" events, got involved in politics, and made sculptures from unusual materials. Their works included video art and performance art.

In its early years, some people thought Fluxus artists were just "pranksters" because of their playful style. Fluxus is also seen as the beginning of mail art and other experimental art forms. Later artists, like Mark Bloch, created their own versions, like "Fluxpan," to continue Fluxus ideas in a new way.

Fluxus artists preferred to work with materials they had on hand. They either made their own work or collaborated with friends. They usually didn't hire companies to make their art. Maciunas often put together many Fluxus items by hand. He wanted them to be mass-produced and sold cheaply, unlike expensive, limited-edition art. Dick Higgins's Something Else Press was another big Fluxus publisher, selling books at regular bookstore prices. Higgins also created the term "intermedia" in 1966.

The most common Fluxus art forms are "event scores" and "Fluxus boxes." Fluxus boxes (also called Fluxkits) were collections of cards, games, and ideas organized in small plastic or wooden boxes by George Maciunas.

Event Scores

An event score, like George Brecht's "Drip Music," is a simple script for a performance. It's usually just a few lines long and describes actions to do, not dialogue. Fluxus artists saw event scores as different from "happenings." Happenings could be long and complex, blurring the lines between performers and audience. Event performances were short and simple. They aimed to make everyday things special and challenge traditional art and music.

The idea of the event came from Henry Cowell's music philosophy. He taught John Cage and Dick Higgins. The term "score" means that anyone can perform the work, just like a music score. This connects to Nam June Paik's "do it yourself" idea and Ken Friedman's "musicality." It means anyone can create art from a score, honoring the original artist while freely interpreting the work.

Other creative forms used by Fluxus artists include collage, sound art, music, video, and poetry, especially visual poetry and concrete poetry.

Using Shock

Nam June Paik and other Fluxus artists understood that shock could have a big impact on viewers. They believed shock could make people question their thinking and "awaken" them from being too comfortable. Paik said, "People who come to my concerts or see my objects need to be transferred into another state of consciousness. They have to be high. And in order to put them into this state of highness, a little shock is required..." At one exhibition in 1963, Paik displayed a real cow's head at the entrance to create this shock.

Fluxus Art Ideas

Fluxus was similar to the earlier art movement of Dada. Both emphasized "anti-art" and made fun of how serious modern art was. Fluxus artists used simple performances to show the connections between everyday objects and art, much like Duchamp did with his Fountain.

Fluxus art was often presented as "events." George Brecht defined an event as "the smallest unit of a situation." Events had minimal instructions, allowing for accidents and unexpected results. Audience members were often included, making them part of the art, just as Duchamp believed the viewer completed the artwork.

The main ideas of Fluxus art can be summed up in four points:

- Fluxus is intermedia: Artists liked to mix different art forms. They used everyday objects, sounds, images, and words to create new combinations.

- Fluxus works are simple: The art was small, the texts were short, and the performances were brief.

- Fluxus is fun: Humor was always an important part of Fluxus.

Fluxus Artists

Fluxus artists were known for their wit and "childlikeness." They didn't have a strict identity, which allowed many different artists to join, including a large number of women. This was important because it followed the abstract expressionism movement, which was mostly white men. However, George Maciunas wanted to keep the group unified. He was sometimes accused of removing members who didn't follow his ideas of Fluxus.

Many artists, writers, and composers were part of Fluxus, including:

- Eric Andersen (born 1940)

- John Armleder (born 1948)

- Ay-O (born 1931)

- Mary Bauermeister (1934-2023)

- Joseph Beuys (1921–1986)

- Bazon Brock (born 1936)

- Joseph Byrd (born 1937)

- John Cage (1912–1992)

- George Brecht (1926–2008)

- Giuseppe Chiari (1926–2007)

- Henning Christiansen (1932–2008)

- Philip Corner (born 1933)

- Jean Dupuy (1925–2021)

- Öyvind Fahlström (1928–1976)

- Robert Filliou (1926–1987)

- Simone Forti (born 1935)

- Henry Flynt (born 1940)

- Ken Friedman (born 1949)

- Al Hansen (1927–1995)

- Geoffrey Hendricks (1931–2018)

- Bici Hendricks (born 1932)

- Dick Higgins (1938–1998)

- Davi Det Hompson (1939–1996)

- Alice Hutchins (1916–2009)

- Toshi Ichiyanagi (born 1933)

- Terry Jennings (1940–1981)

- Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

- Joe Jones (1934–1993)

- Allan Kaprow (1927–2006)

- Bengt af Klintberg (born 1938)

- Milan Knížák (born 1940)

- Alison Knowles (born 1933)

- Arthur Köpcke(1928–1977)

- Takehisa Kosugi (1938–2018)

- Philip Krumm (born 1941)

- Shigeko Kubota (1937–2015)

- George Landow (1944–2011)

- Vytautas Landsbergis (born 1932)

- John Lennon (1940–1980)

- Jackson Mac Low (1922–2004)

- Richard Maxfield (1927–1969)

- George Maciunas (1931–1978)

- Jonas Mekas (1922–2019)

- Gustav Metzger (1926–2017)

- Larry Miller (born 1944)

- Kate Millett (1934–2017)

- Charlotte Moorman (1933–1991)

- Maurizio Nannucci (born 1939)

- Yoko Ono (born 1933)

- Robin Page (1932–2015)

- Nam June Paik (1932–2006)

- Ben Patterson (1934–2016)

- Terry Riley (born 1935)

- Dieter Roth (1930–1998)

- Takako Saito (born 1929)

- Wim T. Schippers (born 1942)

- Tomas Schmit (1943–2006)

- Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019)

- Mieko Shiomi (born 1938)

- Gianni-Emilio Simonetti (born 1940)

- Daniel Spoerri (born 1930)

- James Tenney (1934–2006)

- Yasunao Tone (born 1935)

- Peter Van Riper (1942-1998)

- Ben Vautier (born 1935)

- Wolf Vostell (1932–1998)

- Yoshi Wada (1943–2021)

- Robert Watts (1923–1988)

- Emmett Williams (1925–2007)

- La Monte Young (born 1935)

Scholars and Critics of Fluxus

|

|

Major Collections and Archives

- Alternative Traditions in Contemporary Art, University Library and University of Iowa Museum of Art, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

- Archiv Sohm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany

- Archivio Conz, Verona, Italy

- Artpool, Budapest, Hungary

- Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California

- Emily Harvey Foundation, New York City, and Venice, Italy

- David Mayor/Fluxshoe/Beau Geste Press papers, Tate Gallery Archive, Tate Britain, London, England

- Fluxeum, collection Ute and Michael Berger, Wiesbaden-Erbenheim, Germany

- Fluxus Collection, Ken Friedman papers, Tate Gallery Archive, Tate Britain, London, England

- Fluxus Collection, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

- Fondation du Doute

- FONDAZIONE BONOTTO, Molvena, Vicenza, Italy

- Franklin Furnace Archive, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

- George Maciunas Memorial Collection, The Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA

- Gilbert and Lila Silverman, Fluxus Foundation, Detroit, Michigan, and New York City, USA

- Museo Vostell Malpartida Cáceres, Spain

- Museum Fluxus+ Potsdam, Germany

- Jean Brown papers, 1916–1995 finding aid, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

- Sammlung Maria und Walter Schnepel, Bremen, Germany

- Institute for the Arts & Science, University of California, Santa Cruz, USA

- De Montfort University, Leicester, UK

- TVF The Endless Story of FLUXUS, Gent, Belgium

- Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center, Vilnius, Lithuania

- The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Gift from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection, Detroit, to American Friends of the Israel Museum

- In 2023, Sub Rosa records released a collection of Fluxus sound works on CD entitled Fluxus & NeoFluxus / Stolen Symphony

See also

In Spanish: Fluxus para niños

In Spanish: Fluxus para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |