Fort Runyon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fort Runyon |

|

|---|---|

| Part of Washington, D.C.'s Civil War defenses | |

| Arlington, Virginia | |

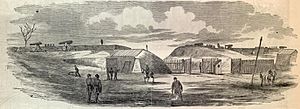

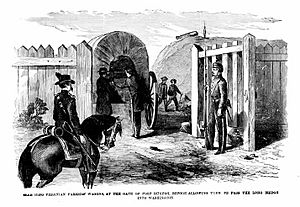

An interior sketch of Fort Runyon, showing activity at the fort during August 1861. The Capitol building is faintly visible in the background, across the Potomac River.

|

|

| Coordinates | 38°52′11″N 77°02′44″W / 38.869722°N 77.045556°W |

| Type | Timber fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Union Army |

| Condition | Dismantled |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1861 |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1861–1865 |

| Materials | Earth, timber |

| Demolished | 1865 |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Fort Runyon was a fort built from timber and earth by the Union Army during the American Civil War. It was constructed in 1861 to protect the southern entrances to the Long Bridge in Washington, D.C.. This fort was a key part of the city's defenses.

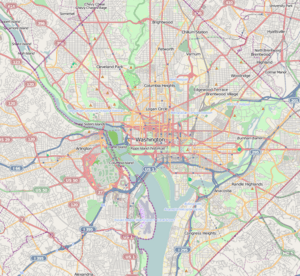

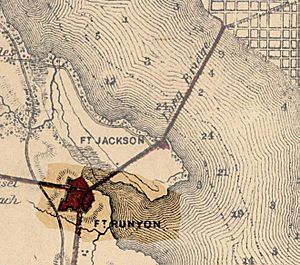

The fort was shaped like a pentagon and was located near where the Pentagon building stands today. It was built right after Union forces moved into northern Virginia on May 24, 1861. Fort Runyon was the largest fort in the ring of defenses around Washington. It was named after Brigadier General Theodore Runyon. Union soldiers stayed at the fort until it was taken apart in 1865 after the war ended. Today, nothing remains of the fort, but a historical marker shows where it once stood.

Contents

Why Fort Runyon Was Built

Before the Civil War, Arlington County (then called Alexandria County) was mostly farmland. It was very close to Washington, D.C. In 1847, this land became part of Virginia again after being part of D.C. for a while. Most people lived in the city of Alexandria. The rest of the county had farms and a famous house called Arlington House.

Virginia Decides to Leave the Union

After Fort Sumter was attacked in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to stop the rebellion. This made many Southern states angry, and they started talking about leaving the Union. Virginia decided to vote on whether to secede (leave the Union).

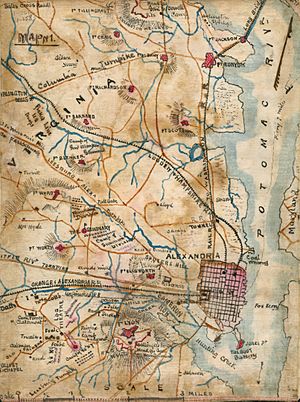

Brigadier General Joseph K. Mansfield, a Union commander, believed that northern Virginia should be taken over quickly. He worried that the Confederate Army might put cannons on the hills of Arlington and shell Washington. He also wanted to build forts on the Virginia side of the Potomac River to protect the bridges. His leaders agreed but waited until Virginia voted.

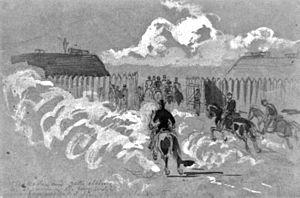

On May 23, 1861, Virginia voted to leave the Union. That night, Union troops began crossing the bridges from Washington, D.C., into Virginia. The New York Herald newspaper described the march as very impressive. Thousands of soldiers, cavalry, and artillery crossed the bridges.

Union Troops Enter Virginia

The Union takeover of northern Virginia was mostly peaceful. However, in Alexandria, a Union officer named Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth was killed. He was shot by a hotel owner while trying to remove a Confederate flag flying over the hotel. Ellsworth was one of the first soldiers to die in the Civil War.

Building Fort Runyon

More than 13,000 Union soldiers marched into northern Virginia on May 24, 1861. They brought tools like shovels and wheelbarrows. Engineers, led by Colonel John G. Barnard, started building forts and trenches along the Potomac River to protect the bridges. By sunrise on May 24, work had already begun on the first two forts: Fort Runyon and Fort Corcoran.

Fort Runyon was named after Brigadier General Theodore Runyon. He commanded one of the first groups of volunteer soldiers from New Jersey. He later led his troops in the First Battle of Bull Run.

Soldiers from New Jersey regiments and the 7th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment helped build Fort Runyon. Engineers directed the work. The land for the fort was taken from James Roach, a building contractor. Soldiers dug trenches and used parts of his property. Another area, Jackson City, which had gambling places, was also cleared for the fort and Fort Jackson.

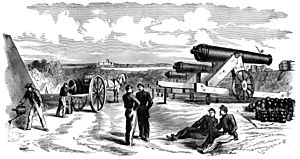

Fort Runyon was designed to be the largest fort protecting Washington because of the important Long Bridge. It had a perimeter of about 1,484 yards (1,357 meters). It was armed with 21 cannons and needed over 2,000 soldiers to defend it. The fort was shaped like a pentagon, with walls facing different directions. It had large gates for wagons and people traveling on the roads that led to the Long Bridge. Fort Runyon acted as a checkpoint for anyone entering Washington from Virginia.

Challenges of the Location

The engineers had surveyed the land for Fort Runyon before the Union troops arrived. They chose the first high ground south of the Long Bridge. This seemed like a good spot for the fort's walls.

However, within a week, problems with the fort's location became clear. Fort Runyon was overlooked by the higher ground of Arlington Heights. An enemy force could hide behind these heights and approach the fort without being seen. To fix this, Colonel Barnard ordered another fort, Fort Albany, to be built on top of the ridge. Even with this issue, work on Fort Runyon continued.

Changes and Later Use

After the Union Army lost the First Battle of Bull Run, there was a rush to make the forts stronger. People worried that the Confederates might attack Washington. Many temporary trenches and blockhouses were later improved and made into permanent defenses around Fort Runyon.

In July 1861, Major General George B. McClellan took command of the Washington military district. He was very concerned about how weak the city's defenses were. He ordered Colonel Barnard to build a continuous line of defenses all around Washington. By March 1862, this line of forts and trenches protected the entire city, including Alexandria and the Chain Bridge.

These defenses south of the Potomac River were called the Arlington Line. They were so strong that no Confederate force ever seriously tried to attack them. Because of these new, stronger forts, Fort Runyon became less important. It was now an "interior" fort, meaning it was behind the main line of defense. Its cannons were moved to other forts that needed them more.

However, Fort Runyon still had some importance. It remained a checkpoint for wagons and trains entering Washington via the Long Bridge. By 1863, it mostly had a small guard.

Fort Runyon During the War

After the Battle of Bull Run, Fort Runyon served as a meeting point for engineering troops who had been scattered during the Union defeat. They regrouped at the fort and were then sent to build more trenches to protect Washington.

From July to August 1861, the 21st New York Volunteer Infantry was stationed at the fort. Later, in November 1861, soldiers from the 14th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry garrisoned the fort. By 1863, only one company of soldiers remained there.

In May 1864, a report by Brigadier General A.P. Howe said that Fort Runyon was "out of repair and at present unoccupied." He recommended that it be fixed and used again because it was an important location at the head of the Long Bridge.

After the War

After General Robert E. Lee's army surrendered in April 1865, the main reason for the forts around Washington was gone. Fort Runyon was considered unimportant to the overall defenses, so it was abandoned.

The fort's cannons were removed, and the soldiers went home. Because it was close to Washington, many squatters, mostly African-American people, moved into the abandoned fort. They used the fort's timber and wood for firewood and building materials for their homes.

Even though the wood parts of the fort were taken apart, the earth embankments and trenches lasted longer. A 1901 tour guide even mentioned that tourists could still see the decaying Fort Runyon from their train windows.

However, new bridges built in the early 1900s destroyed what little remained of Fort Runyon. The new railroad bridge (1903) and highway bridge (1906) went right through the old fort's earthworks. These were leveled to make way for trains and cars. By 1941, when work began on the Pentagon, nothing was left of the fort. Today, Interstate 395 runs through the site, and a historical marker remembers the fort.

Images for kids