Civil War Defenses of Washington facts for kids

|

Civil War Fort Sites

|

|

Union Army soldiers with the 3rd Massachusetts Heavy Artillery Regiment at Fort Totten in Washington, D.C. in August 1865

|

|

| Location | Washington, D.C. Fairfax County, Virginia Prince George's County, Maryland |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 74000274 (original) 78003439 (increase) |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | July 15, 1974 |

| Boundary increase | September 13, 1978 |

The Civil War Defenses of Washington were a group of Union Army fortifications (like small forts) that protected the United States' capital city, Washington, D.C.. They kept it safe from attacks by the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Many of these old forts are now managed by the National Park Service. They are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which means they are important historical sites. Other forts are part of state, county, or city parks. Some are even on private land. A special trail connects many of these sites.

You can still see parts of some of these old earthworks today. Other parts have been taken down over time.

Contents

Protecting Washington: Civil War Forts

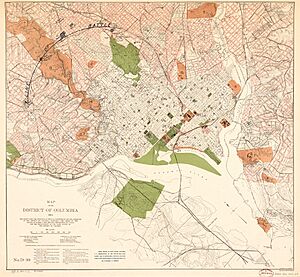

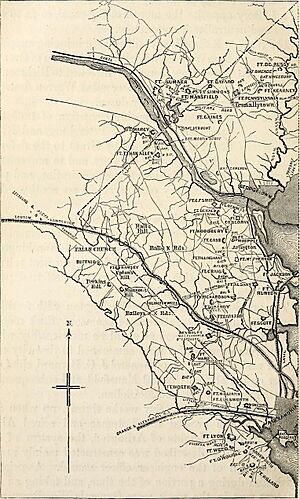

During the American Civil War, the Union army built a huge defense system around Washington, D.C. This system included 68 large forts. These forts held soldiers, cannons, and other important supplies.

They also built 93 smaller places for cannons, called batteries. There were seven blockhouses, which were strong, small buildings. Soldiers also dug 20 miles of trenches and built 30 miles of military roads. The Confederate army never captured any of these forts. However, some did come under attack.

Most of these forts were built on the edges of the city. This land was mostly farms and private property. The military took over this land when the war began.

Stories of the Forts and Their Land

Building these forts meant taking over private land. This often caused problems for the people who lived there. Here are some examples:

- Fort Slemmer: This fort was built on a 24-acre flower farm. The owner, Henry Douglas, lost all his flowers, fruit trees, and plants. He could no longer work as a florist.

- Fort Reno: The army used the farmhouse on Giles and Miles Dyer's land as their headquarters. The fort itself covered 20 acres. Another 50 acres were used for soldier camps and training.

- Forts Chaplin and Craven: These forts were built on Selby B. Scaggs' large farm. He owned about 400 acres. Several workers also lived on his farm.

- Fort DeRussy: This fort was built on land owned by Bernard S. Swart, a clerk. He lived there with his family and two farmhands. Today, this land is part of Rock Creek Park.

- Fort DuPont: This fort was built on Michael Caton's land. He was 60 years old and lived there with his wife, five adult children, and one domestic worker.

- Fort Stevens: This fort was built on land belonging to Emory Methodist Church. Some land may have belonged to Elizabeth Thomas, a free Black woman. Her house was torn down for the fort.

The forts in Washington, D.C., were built to be temporary. They were mostly made of earth, wood, and some stone. They had deep ditches and sharp obstacles (called abatis) around them. The plan was to give the land back to its owners after the war.

Most landowners lost their property during the war. They could not earn money from their land. Only a few received any payment or rent from the government.

From Forts to Parks: The "Fort Circle" Idea

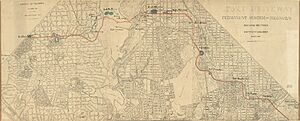

In 1898, people started thinking about connecting the forts with a road. This "Fort Drive" would link all the forts around the city.

In 1919, leaders in Washington, D.C., asked Congress to create a "Fort Circle" system of parks. This would turn the old forts into a green ring of parks around the growing city. A road would connect them, allowing people to easily visit. However, the bill to buy back the land (which had been returned to private owners) did not pass.

But in 1925, a similar bill finally passed. This led to the creation of the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC). Their job was to buy the land where the old forts stood. For example, the site of Fort Stanton was bought in 1926. Over the years, different groups worked on buying land and building these parks. By the 1940s, the National Park Service took control.

During the Great Depression, groups like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) helped improve these parks. They trimmed trees, cleared brush, and built park buildings. There were also ideas for other buildings, like a school or a water tower. But World War II stopped these plans. After the war, budget cuts further delayed the "Fort Drive."

By 1963, Washington, D.C., had grown far beyond the ring of forts. City roads already connected the parks, even if not in a perfect circle. The idea of a grand "Fort Circle Drive" was eventually dropped. Instead, a plan for a Fort Circle Trail was developed. This trail would connect the parks for walking and biking.

Who Manages the Forts Today?

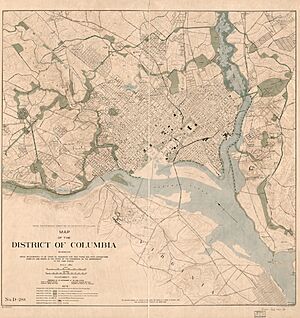

Different parts of the National Park Service manage the fort sites today.

- The National Capital Parks-East unit manages forts like Foote, Greble, Stanton, and Dupont. These are in Washington, D.C., and Maryland.

- The Rock Creek Park unit manages forts like Bunker Hill, Totten, Stevens, and DeRussy. These are all in Washington, D.C. They also manage Battleground National Cemetery.

- The George Washington Memorial Parkway manages Fort Marcy in Virginia.

In 2024, there was a proposal to make the forts a national historical park. However, the National Park Service preferred to keep the current way of managing them.

The Fortifications: A List

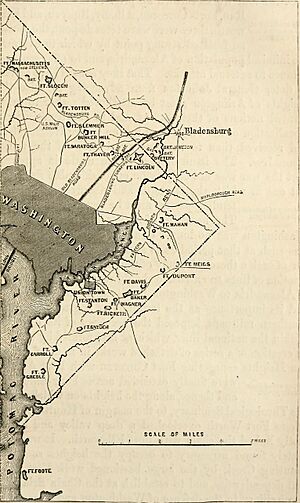

The 1865 map shows many fortifications that protected Washington, D.C. Some of these no longer exist. The forts listed in italic type are included on the National Register of Historic Places.

Northwest Quadrant

- Fort Cross (MD)

- Fort Kirby (MD)

- Fort Sumner (MD)

- Battery Alexander (MD)

- Fort Simmons (MD)

- Fort Davis (MD)

- Battery Benson (MD)

- Battery Bailey (MD)

- Fort Mansfield (MD)

- Battery Cameron

- Battery Parrott

- Battery Kemble

- Battery Martin Scott

- Battery Vermont

- Fort Bayard

- Fort Gaines

- Fort Reno

- Battery Rossell

- Fort Kearny

- Battery Terrill

- Battery Smead

- Battery Kingsbury

- Fort De Russy

- Battery Sill

- Fort Stevens

Northeast Quadrant

Eastern Branch

- Fort Mahan

- Fort Chaplin

- Fort Meigs

- Fort Dupont

- Fort Davis

- Fort Baker

- Fort Wagner

- Fort Ricketts

- Fort Stanton

- Fort Snyder

- Fort Carroll

- Fort Greble

Potomac Approaches

Arlington Line – Virginia

From North to South:

- Fort Marcy

- Fort Ethan Allen

- Fort C. F. Smith

- Fort Bennett

- Fort Strong (formerly Fort DeKalb)

- Fort Corcoran

- Fort Haggerty

- Fort Morton

- Fort Woodbury

- Fort Cass (later within Fort Myer)

- Fort Whipple (later within Fort Myer)

- Fort Tillinghast

- Fort McPherson

- Fort Buffalo

- Fort Ramsay

- Fort Craig

- Fort Albany

- Fort Jackson

- Fort Runyon

- Fort Richardson

- Fort Barnard

- Fort Berry

- Fort Scott

- Battery Garesche

- Fort Reynolds

- Fort Ward

- Fort Worth

- Fort Williams

- Fort Ellsworth

- Fort Lyon

- Fort Farnsworth

- Fort Weed

- Fort O'Rourke

- Fort Willard

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |