Fort Greble facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fort Greble |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil War defenses of Washington, D.C. | |

| Congress Heights, District of Columbia | |

| Coordinates | 38°49′38″N 77°00′53″W / 38.82722°N 77.01472°W |

| Type | Earthwork fort |

| Site history | |

| Built | Fall, 1861 |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1861–1869 |

| Materials | Earth, timber |

| Demolished | 1869 |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | One company, Seventh Unattached Heavy Artillery regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers (125 men) |

Fort Greble was a special kind of fort built during the American Civil War. It was part of the defenses that protected Washington, D.C. from attacks. The fort was named after First Lieutenant John Trout Greble. He was the first graduate from West Point to die in the war.

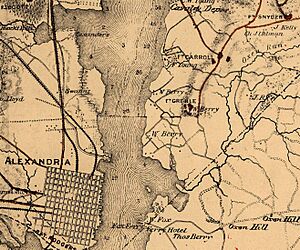

Fort Greble was built on a high spot called Congress Heights. From there, it could protect where the Anacostia and Potomac rivers meet. Its location also stopped enemies from bombing the Washington Navy Yard and other parts of the city. Other forts, like Fort Carroll and Fort Foote, helped protect Fort Greble. Even though it was built for battle, Fort Greble never fired its guns during the war. After the war, it was used for a short time as a training place for the U.S. Army's Signal Corps. Then, it was closed down. Today, the land where Fort Greble once stood is a community park.

Contents

Building the Fort: A Quick Plan

Before the Civil War started, the area known as Congress Heights belonged to the Berry family. You could see the Capitol building from the top of these hills. After a big battle called the First Battle of Bull Run, people in the Union were very worried. They thought the Confederate army might attack Washington, D.C. So, they quickly built defenses around the city.

Many forts were built on land that was rented or leased. But General George B. McClellan took command in July 1861. He found that no defenses had been started on the Maryland side of the Potomac River. This meant enemies could easily bomb the city from nearby hills.

Because of this, building forts sped up and spread out. New strong points and places for cannons were built all around the 37-mile (60-km) edge of the District of Columbia. To stop an attack from the unprotected Maryland side, Brigadier General John G. Barnard ordered several forts to be built on Congress Heights. These forts would protect the Navy Yard and Washington Arsenal from being bombed. Fort Greble was planned for the important western end of these heights.

The plans for the new forts moved quickly. By the end of September 1861, work began on what would become Fort Greble. U.S. Army engineers led the construction. The fort was built as several smaller forts that supported each other. It was finished before Christmas that year. General Barnard reported that Forts Greble and Stanton were "completed and armed" by December 10, 1861.

The fort was named after Lt. John Trout Greble, who died at the Battle of Big Bethel. Fort Greble had a perimeter of 327 yards (about 300 meters). It had space for 17 guns. In 1862, a report praised Fort Greble as a "large and powerful work." It had good places for ammunition and bomb-proof shelters. However, the report also suggested new gun platforms and better protection for the soldiers using the guns.

Because the fort was built so fast, it lacked some features found in later forts. For example, in 1864, an engineer asked for the wooden buildings used by soldiers to be removed. This was so safer ammunition storage areas could be built. These kinds of improvements continued throughout the war.

Fort Greble During the War

Fort Greble was not meant to be part of a continuous line of forts. Instead, it and other forts on the east side of the Potomac River had a special job. They were there to stop the Confederacy from bringing cannons across the Potomac. This would prevent them from bombing the Washington Navy Yard.

A report from December 1862 explained this clearly. It said that an enemy would likely not try to enter Washington from this direction. The main goal was to stop them from setting up batteries to destroy the navy-yard and arsenal. The forts needed to be able to defend themselves. They would only need a small group of soldiers for help.

These words turned out to be true. Fort Greble was never attacked by Confederate forces during its four years of active duty. The soldiers stationed there were rotated regularly and served quietly behind the fort's earthen walls.

Daily Life at the Fort

Life for soldiers at Fort Greble was much like that at other forts defending Washington. A soldier's day started before sunrise with a bugle call called reveille. This was followed by morning muster, where soldiers were counted and reported if they were sick. After muster, the day was spent improving the fort's defenses and practicing drills. This included gunnery practice, infantry drills, and parade drills.

This schedule continued, with breaks for meals and rest, until taps was called in the evening. Sundays were different. After muster, there was a weekly inspection and church service. Sunday afternoons were free time for soldiers. They often used this time to write letters home, bathe, or catch up on sleep.

For much of the year, soldiers faced challenges like mosquitoes, heat, and humidity. Even though Fort Greble was on a hill, the area around it was swampy. This was a perfect breeding ground for malaria. Supplies usually arrived weekly by military road. Trips to Washington or Uniontown were rare. Fort Greble was quite isolated, even from its nearby forts.

Until 1864, messages between Fort Greble and its neighbors had to go through headquarters in Washington. After this system failed, efforts were made to set up signaling points between the forts. The forts were also connected to Washington by telegraph wire. Signal teams sometimes visited Fort Greble for training.

Who Guarded the Fort?

In October 1861, General Barnard made a plan for how many soldiers each fort should have. "Rear line" forts like Fort Greble were supposed to have one soldier for every yard of their perimeter. Front-line forts would have two soldiers per yard if needed. However, most forts were not always fully staffed.

Fort Greble had a perimeter of 327 yards (about 300 meters). Barnard suggested a force of 165 men for it. If an attack was coming, more soldiers would be sent from Washington's reserve force. Barnard noted that it was "seldom necessary to keep these infantry supports attached to the works."

This plan was only for the soldiers guarding the fort's walls. It didn't include the artillerymen who operated the guns. Barnard planned for three crews for each gun. These crews would live at the fort permanently. To operate Fort Greble's 15 planned guns, 255 artillerymen were assigned. However, the needs of the war often changed these plans. As the fighting continued, soldiers were often moved from Washington's forts to fight in battles. By 1864, Washington had less than half the soldiers Barnard had recommended.

In May 1864, a report by General Albion P. Howe stated that Fort Greble's garrison was one company of the Seventh Unattached Heavy Artillery, Massachusetts Volunteers. Captain George S. Worcester commanded 125 men. They operated six 12-pounder field howitzers, six 32-pounder barbette guns, one 8-inch siege howitzer, one Coehorn mortar, one 10-inch mortar, and one 30-pounder Parrott rifle. The report also said the garrison was "drilled some at artillery and infantry," which was better than some other nearby forts.

After the War: A New Purpose

After General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia surrendered in April 1865, the main reason for defending Washington ended. Engineers suggested that forts be put into three groups. First-class forts would stay active. Second-class forts would be stored and kept ready. Third-class forts would be completely abandoned. Fort Greble was placed in the second-class group.

This meant that guns and ammunition from forts that were being taken apart would be stored. Fort Greble was chosen as one of these storage places. As a second-class fort, it continued to receive regular care. However, by August 1865, money was running out. More and more forts were closed down, and the land was given back to its original owners.

In August 1867, the commander of the Department of Washington asked how much longer Fort Greble was needed as a storage place for military supplies. When possible, the Ordnance Department moved its property to the Washington Arsenal (now Fort McNair) or to other forts that were still active.

The new Army Signal Corps, which had been important in the Civil War, needed a training ground after the war. In 1866, the Army allowed General Albert J. Myer, the Chief Signal Officer, to use Fort Greble for this purpose. In 1868, Myer gained control of Fort Greble to use it as a school. Here, soldiers learned about electric telegraphy and visual signaling. But in January 1869, Myer moved the school to Fort Whipple, Virginia.

After the Signal Corps left, the fort's land was sold back to private owners. Later, the land was bought to become a park. For many years, there were plans to connect Fort Greble and other forts with a "Fort Circle Drive" around Washington. This road would be 23.5 miles (37.8 km) long. But these plans never happened because of money problems and political issues. Many forts, including Fort Greble, did become parks. However, they were not connected in a grand plan. Today, the site of Fort Greble is home to the Fort Greble Recreation Center. It's a community center for young people and neighborhood events. In 2006, a lighted baseball field was built there as part of a city-wide park renovation.