Frank Marshall Davis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

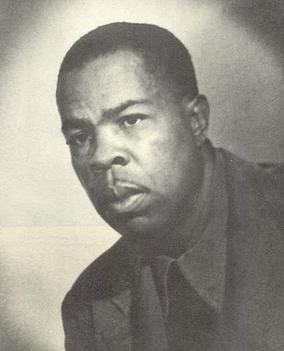

Frank Marshall Davis

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | December 31, 1905 Arkansas City, Kansas, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 1987 (aged 81) Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Pen name | Frank Boganey |

| Occupation | Journalist, poet |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Social realism |

| Subject | Race relations, music, literature, American culture |

| Literary movement | Social realism |

Frank Marshall Davis (born December 31, 1905 – died July 26, 1987) was an American journalist and poet. He was also an activist who worked for fairness in society and for workers' rights.

Davis started his career writing for Black newspapers in Chicago. He later moved to Atlanta, where he helped make the Atlanta Daily World a successful daily newspaper. He then returned to Chicago. During this time, he wrote about important social and political issues. He also covered topics like sports and music. His poetry was supported by the government's Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the New Deal era. He was also an important part of the South Side Writers Group in Chicago. He is known as one of the key writers of the Black Chicago Renaissance.

In the late 1940s, Davis moved to Honolulu, Hawaii. There, he ran a small business and became involved in local efforts to help workers. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) kept an eye on his activities, as they often watched people involved in union work.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Frank Marshall Davis was born in Arkansas City, Kansas, in 1905. His parents divorced, and he grew up living with his mother, stepfather, and grandparents. He finished high school in Arkansas City.

In 1923, when he was 17, he went to Friends University. From 1924 to 1927, and again in 1929, he attended Kansas State Agricultural College, which is now Kansas State University.

When Davis started at Kansas State, about 25 other African American students were there. In Kansas at that time, Black people were often kept separate from white people, even if there wasn't a law saying so. Davis studied journalism. He started writing poems for a class and was encouraged by his English teacher to keep writing poetry. He joined the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity in 1925. He left college before getting his degree.

Starting His Career in Chicago

In 1927, Davis moved to Chicago. Many African Americans moved to northern cities like Chicago during the Great Migration. They were looking for better jobs and opportunities.

Davis worked for several Black newspapers, including the Chicago Evening Bulletin and the Chicago Whip. He also wrote articles and short stories for Black magazines. During this time, he started writing serious poetry, including a long poem called Chicago's Congo, Sonata for an Orchestra.

In 1931, Davis moved to Atlanta to become an editor for a newspaper. Later that year, he became the managing editor. In 1932, the paper was renamed the Atlanta Daily World. It became the first successful daily newspaper for Black people in the United States. Davis kept writing and publishing poems. His first book of poems, Black Man's Verse, was published in 1935.

Return to Chicago and Activism

In 1935, Davis moved back to Chicago. He became the managing editor of the Associated Negro Press (ANP), a news service for Black newspapers. He stayed in this role until 1947. In Chicago, Davis also started a photography club. He worked with different political groups and was part of the League of American Writers. He loved photography and even inspired writer Richard Wright to take up photography.

Davis, Richard Wright, and Margaret Walker were part of the South Side Writers Group. This group met regularly starting in 1936 to share and improve their writing. They were important figures in what is known as the Black Chicago Renaissance.

Davis also worked as a sports reporter. He famously covered the boxing matches between African American boxer Joe Louis and German boxer Max Schmeling. He and other writers saw these fights as a symbol of democracy and equality fighting against unfairness. Davis used his journalism to call for sports to be open to everyone, regardless of race. He believed sports could help break down racial barriers.

During the Great Depression, Davis worked for the federal Federal Writers' Project. This was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, which created jobs and helped people during tough economic times. In 1937, he received a special grant called a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship.

Toward the end of World War II, Davis started a newspaper in Chicago called The Star. This paper aimed to encourage cooperation between different groups and avoid unfair accusations.

In 1945, Davis taught one of the first courses on jazz history in the United States. In 1948, he published a collection of poems called 47th Street: Poems. This book described the lives of African Americans on Chicago's South Side.

Davis was a strong supporter of a "raceless" society. He believed that the idea of "race" was not logical and caused division. He was a member of the Civil Rights Congress and worked for civil liberties. He supported the Progressive Party, which aimed for social and economic reforms. In his memoir, Livin' the Blues, Davis wrote that he worked with many different groups. He said his main goal was to fight against white supremacy. Because of his views, some libraries removed his books, and the FBI investigated him in the 1940s and 1950s.

Life and Work in Hawaii

In 1948, Frank Marshall Davis and his second wife moved to Honolulu, Hawaii. Davis wrote a weekly column called "Frank-ly Speaking" for the Honolulu Record. This was a newspaper for workers published by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). At first, Davis wrote about workers' issues. Later, he wrote about culture, politics, and especially racism. He also explored the history of blues and jazz music in his columns. He published less poetry during this time, but his final book of poems, Awakening, and Other Poems, came out in 1978.

In 1973, Davis visited Howard University in Washington, D.C., to read his poetry. This was his first visit to the U.S. mainland in 25 years. His work started to appear in collections of poems. This happened because there was new interest in Black writers due to the Civil Rights Movement.

Frank Marshall Davis passed away in July 1987, in Honolulu, at the age of 81. After his death, three more of his works were published: Livin' the Blues: Memories of a Black Journalist and Poet (1992), Black Moods: Collected Poems (2002), and Writings of Frank Marshall Davis: A Voice of the Black Press (2007).

Personal Life

Davis was married to Thelma Boyd, his first wife, for 13 years. They lived in different cities for a time while he worked in Chicago.

In 1946, he married Helen Canfield. She was 18 years younger than him. Davis and Canfield divorced in 1970. Davis had one son, Mark, and four daughters: Lynn, Beth, Jeanne, and Jill.

Legacy and Influence

Kathryn Waddell Takara, a scholar, said that Davis kept writing a lot even when he didn't get much money or recognition. She noted that he stuck to his belief that to achieve fairness, people needed to openly talk about racial issues in an unfair society. He showed other writers how to hold onto their beliefs and express them.

Davis influenced other poets and publishers, like Dudley Randall. His work also had an impact on the Black Arts Movement. In 2018, he was honored and added to the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

In Barack Obama's memoir Dreams from My Father (1995), he mentions a friend of his grandfather in Hawaii. Obama later said this friend was Frank Marshall Davis. Obama said Davis told him that he and Obama's grandfather, Stanley Armour Dunham, grew up near each other in Kansas. However, they didn't meet until they both lived in Hawaii. Davis described how race relations were in Kansas back then, including Jim Crow rules that kept Black people separate. He believed there hadn't been much progress since then. Obama remembered Davis as someone who strongly believed in Black Power and fairness.

Selected Works

- Black Man's Verse; Black Cat, (Chicago, IL), 1935.

- I Am the American Negro, Black Cat, (Chicago, IL), 1937, ISBN: 978-0-8369-8920-5

- Through Sepia Eyes; Black Cat, (Chicago, IL), 1938.

- 47th Street: Poems; Decker (Prairie City, IL), 1948.

- Black Man's Verse; Black Cat (Skokie, IL), 1961.

- Jazz Interludes: Seven Musical Poems; Black Cat (Skokie, IL), 1977.

- Awakening and Other Poems; Black Cat (Skokie, IL), 1978.

- Livin' the Blues: Memoirs of a Black Journalist and Poet, ed. John Edgar Tidwell; University of Wisconsin Press, 1992, ISBN: 978-0-299-13500-3

- Black Moods: Collected Poems, ed. John Edgar Tidwell; University of Illinois Press, 2002, ISBN: 978-0-252-02738-3

- Writings of Frank Marshall Davis: A Voice of the Black Press, ed. by John Edgar Tidwell; University Press of Mississippi, 2007. ISBN: 1-57806-921-1; ISBN: 978-1-57806-921-7

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |