Franklin Gritts facts for kids

Franklin Gritts, also known as Oau Nah Jusah, was a famous Cherokee artist. His Native American name means "They Have Returned." He lived from 1914 to 1996. Gritts was known for his art and for teaching other artists.

During World War II, he served in the Navy. He was on the USS Franklin, a ship that was badly damaged in a big attack. He was hurt but survived and received a Purple Heart medal. Later in life, he became the art director for a famous sports newspaper called The Sporting News. This paper was often called the "Bible of Baseball."

Contents

Early Life and Family

Franklin Gritts was born in Vian, Oklahoma, on August 8, 1914. His father, George Gritts, was a full-blood Cherokee man. George followed traditional Cherokee ways. Franklin's mother, Rachel Gritts, was also a full-blood Cherokee. Both of his parents are listed on the Dawes Rolls, which were records of Native Americans.

Franklin's grandfather, Anderson Gritts, worked to help the Cherokee people. He fought for their land and oil rights in Washington D.C. in the early 1900s. His grandfather was part of a group that came from the Original Keetoowah Society. This was a religious and cultural group that started in the 1850s.

In August 1920, a meeting of the Eastern Emigrant and Western Cherokee Association happened at George Gritts’ farm. People came on foot, horseback, in wagons, and even a few cars. They set up a camp in the fields. Franklin was five years old at the time. He thought everyone had come for his birthday! This was his first memory.

Starting School

Franklin's parents were worried about sending him to school. They had lost other children when they were young. So, they kept Franklin at home until he was eight years old. School officials finally said he had to attend. His parents agreed, even though they were not happy about it.

Franklin spoke little English when he started school. He was also older than the other first-graders. But he loved school right away. His teachers were kind and helped him catch up quickly. Most of the students were not Native American. Still, they quickly became friends with the shy new boy. Franklin showed a talent for art early on. This made him even more popular. By high school, he played sports and felt comfortable both at home and at school.

College Education

When Franklin was a senior in high school, officials from the Bureau of Indian Affairs talked to him. They suggested he go to Bacone College. This was a college for Native American students in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Franklin gladly accepted. He spent two years at Bacone, where Native American art was an important part of his studies.

He did so well that the Bureau of Indian Affairs offered him a loan. This loan would help him attend the University of Oklahoma in Norman, Oklahoma. This was a big step! Bacone was small and close to home. The University of Oklahoma was huge. But Franklin did not hesitate. He knew it was a great chance. The country was in the Great Depression, and money was very hard to find. He could not have gone to the university without this loan and encouragement.

The dean of the School of Fine Arts at the university was Dr. O. B. Jacobson. He was a Swedish-American man who loved American Indian art. He valued his Native American students. But he also expected them to meet high art standards. He encouraged them to work on their Indian art as a special project. So, Gritts studied portrait painting, figure painting, and art history. He also took other general courses.

Gritts earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in painting in 1939. In June 1940, he married Geraldine Monroe. He had met her at the University of Oklahoma.

Teaching Career

After college, Gritts became a teacher at the Fort Sill Indian School in Anadarko, Oklahoma. After one year, he moved to Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas. There, he taught American Indian art to high school and college students. This was a big step up for Gritts. Haskell was a well-known Native American school. Students came from many different tribes and states. He taught small classes, so he could help each student individually.

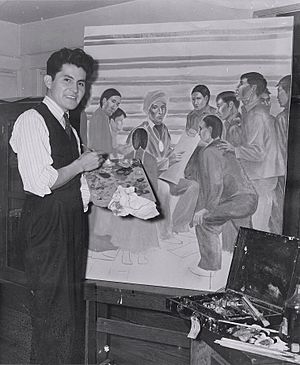

Besides teaching, Gritts painted large pictures called murals. He painted them in different buildings on the Haskell campus. He was also asked to paint a portrait of Peter Graves. Peter Graves was a famous Ojibwe chief. This painting was placed in a US Navy ship.

Serving in World War II

Gritts' peaceful teaching career changed when the United States entered World War II. In 1943, he left Haskell and joined the Navy. He went to basic training in Farragut, Idaho. Then he went to aerial photography school in Pensacola, Florida. This was a new and interesting field for him. But it meant he stopped focusing on his Indian art full-time.

After training, he was sent to the USS Franklin (CV-13). This was an aircraft carrier fighting in the Pacific part of the war. He boarded the ship in Oakland, California. The ship slowly sailed toward Japan. On the way, he took pictures and developed them. He also did other art jobs, like lettering, illustrations, and sign painting.

The USS Franklin fought in many battles. Then, on March 19, 1945, the ship was about 50 miles from Japan. It was getting ready to attack the Japanese homeland. The deck was full of planes with fuel and bombs. Suddenly, a Japanese plane appeared and dropped two bombs. One bomb hit the flight deck and went through to lower decks. It caused huge damage and fires. The second bomb hit the back of the ship.

Seven hundred ninety-eight sailors and Marines were killed. It was the worst disaster the U.S. Navy had ever faced. Amazingly, the ship did not sink, even though it was badly damaged. Because of its service and this attack, the crew of the USS Franklin became the most honored crew in Navy history.

Gritts' Injuries and Recovery

Gritts was in a hallway near the deck when the ship was hit. He was wounded in his left leg and foot by metal pieces called shrapnel. He managed to climb out of a window and into the sea. Other survivors picked him up in a life raft. They spent a cold night on the raft. They drifted away from the damaged ship. As the sun set, they saw it disappear, leaning badly.

The next morning, a destroyer ship rescued them. Gritts received basic first aid. He then began a long journey home across the Pacific. He was transferred from ship to ship. Some ships were ordered back into fighting zones, so he had to keep changing ships until he found one going home.

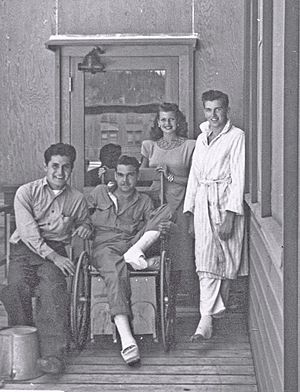

To move between ships on the rough seas, he was attached to heavy cables. His stretcher was pulled over the water. Finally, he arrived in Hawaii. He was able to call home just as the news of the Franklin disaster was announced. In Hawaii, he got his first full medical treatment. Doctors found an infection in his left leg bone. He had also lost a toe on that foot.

After a few weeks, he sailed again on a hospital ship to Oakland. From there, he took a hospital train to Farragut, Idaho. The training camp there had been turned into a hospital. He stayed in this hospital for over a year. The war ended during this time.

Gritts needed more medical care at the Great Lakes Hospital in Chicago. The infection in his leg bone kept draining and would not heal. To pass the time, he drew modern illustrations and cartoons. He drew them to make his fellow patients laugh. Some of his drawings were even published in military magazines.

After he recovered and was released, he returned to Haskell in 1947. He was officially released from the Navy on September 19, 1947. The country was rebuilding after WWII. Many returning soldiers were going to college with help from the G.I. Bill.

Back to Teaching Art

At Haskell, there was a lot of excitement. The school was changing to meet the needs of the modern world. Native American students from all over the country wanted to "Learn to Earn."

Gritts saw that students needed training in commercial art. This is art used for advertising and business. So, he changed his classes to teach commercial art. However, he still helped students who wanted to study traditional Indian art. He also continued his own love for photography.

He created a new commercial art program without any guide. He spent a summer at the Art Institute of Chicago. He also took evening classes at the University of Kansas. This helped him get his state teaching license. Haskell was working to become a member of a group that sets standards for colleges.

One of Gritts’ students after the war was Adam Fortunate Eagle Nordwall. Adam said that Gritts' return and teaching commercial art was a turning point for him. Adam was able to get a job as a commercial artist because of the skills he learned from Gritts. Years later, in 1968, Adam Fortunate Eagle became a main organizer of the Native American occupation of Alcatraz.

Working at Sporting News

After five years at Haskell, Gritts decided to try working in commercial art himself. Housing on campus was difficult for his growing family. He eventually had a daughter, Dara Stillman, and two sons, Bob and Galen Gritts. So, he left his teaching job and moved his family to St. Louis, Missouri.

In 1955, he saw a newspaper ad for an art director at The Sporting News. He got the job. The Sporting News started in 1886. It was a newspaper sent all over the country. It was the most important baseball weekly for fans. It was full of baseball news, stories, and statistics. People called it the "Baseball Bible." In 1955, it was still very popular. It also had a monthly magazine called The Sporting Goods Dealer. This magazine was glossy and had many ads.

Gritts’ job involved putting together articles, photos, and ads for each page of the newspaper. He also created original artwork for the front page. The weekly deadlines were very strict. But he always made sure the paper was published on time. He also prepared The Sporting Goods Dealer magazine each month.

Later Life and Legacy

Franklin Gritts passed away on November 8, 1996. He is buried at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

His art is still celebrated today. Even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt bought one of his paintings. Gritts’ art is shown in important museums. These include the Gilcrease Museum and the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His work is also at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, and the Muskogee Public Library.

Gritts painted a large mural on four walls at Haskell Indian Nations University. It is at the entrance to the auditorium. His oil painting of the great Sequoyah is also there. Sequoyah invented the Cherokee syllabary, which is the Cherokee writing system. Gritts helped people appreciate Native American art. This appreciation continues at Haskell today. The Haskell Indian Art Market is a two-day festival that attracts 30,000 people.

He also illustrated the back cover of a book called The Five Civilized Tribes in 1948. A book for children, The Cherokee, published in 1985, calls Gritts a famous Cherokee.

In 1950, his painting "Stomp Dance" was included in a collection of Native American art. This collection was published in France. In 2009, Gritts' painting Indian Woman Grinding Corn was shown in Cotonou, Benin, in West Africa. This was part of a program called Art in Embassies. This program shares U.S. art with people around the world.

|