Gerard K. O'Neill facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gerard K. O'Neill

|

|

|---|---|

Gerard K. O'Neill in 1977

|

|

| Born |

Gerard Kitchen O'Neill

February 6, 1927 Brooklyn, New York, US

|

| Died | April 27, 1992 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Cornell University |

| Known for | Particle physics Space Studies Institute O'Neill cylinder Mass driver |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physicist |

Gerard Kitchen O'Neill (February 6, 1927 – April 27, 1992) was an American physicist and a big supporter of space exploration. He taught at Princeton University. There, he invented a special device called a particle storage ring. This device helped with experiments about tiny particles.

Later, he created a magnetic launcher known as a mass driver. In the 1970s, he came up with a plan to build homes for people in outer space. One of his designs was called the O'Neill cylinder. He also started the Space Studies Institute. This group helps fund research into building things in space and creating space colonies.

O'Neill started studying tiny particles at Princeton in 1954. He had just finished his advanced studies at Cornell University. Two years later, he shared his idea for a particle storage ring. This invention made it possible to speed up particles much more than before. In 1965, he did the first experiment where two beams of particles crashed into each other.

While teaching at Princeton, O'Neill became very interested in humans living in space. He researched and suggested a future where people could settle in space. He wrote about his idea for the O'Neill cylinder in a paper called "The Colonization of Space." In 1975, he held a meeting at Princeton about building things in space. Many people who later became space supporters attended. O'Neill built his first mass driver prototype with professor Henry Kolm in 1976. He believed mass drivers were key to getting minerals from the Moon and asteroids. His famous book, The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, inspired many people to support space exploration. He passed away in 1992 from leukemia.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Gerard O'Neill was born in Brooklyn, New York, on February 6, 1927. His father, Edward, was a lawyer. His mother was Dorothy. Gerard was an only child. His family moved to Speculator, New York, for a while.

For high school, O'Neill went to Newburgh Free Academy. He worked on the school newspaper. He also had a job as a news reporter at a local radio station. He finished high school in 1944, during World War II. On his 17th birthday, he joined the United States Navy. The Navy trained him to work with radar. This made him very interested in science.

After leaving the Navy in 1946, O'Neill studied physics and math at Swarthmore College. When he was a child, he often talked with his parents about people living in space. In college, he enjoyed working on rocket math problems. But he didn't think space science was a good career path then. So, he chose to study high-energy physics instead. He graduated with high honors in 1950. O'Neill then went to Cornell University for his advanced degree. He earned his PhD in physics in 1954.

O'Neill married Sylvia Turlington in 1950. They had three children: Roger, Janet, and Eleanor. They later divorced in 1966.

O'Neill loved to fly. He was skilled at flying both powered planes and gliders. He even won a special gliding award. In 1973, he met Renate "Tasha" Steffen. She helped him during a glider flight. They got married the day after his flight. They had one son, Edward.

Exploring Tiny Particles

After finishing at Cornell, O'Neill became a teacher at Princeton University. There, he began his research into particle physics. In 1956, he wrote an article about his idea. He thought that particles made by a particle accelerator could be stored for a few seconds. These stored particles could then be made to crash into another beam of particles. This would create much more energy than before. At first, other scientists were not sure about his ideas.

O'Neill became a full professor at Princeton in 1965. He worked with Stanford University to build the Colliding Beam Experiment (CBX). They got money from the Office of Naval Research. In 1958, they started building the first particle storage rings. O'Neill figured out how to catch the particles. He also learned how to create a vacuum to store them long enough for experiments. The CBX stored its first particle beam in 1962.

In 1965, O'Neill worked with Burton Richter on the first experiment where particle beams collided. They used particle beams from the Stanford Linear Accelerator. These beams were collected in O'Neill's storage rings. Then, they were made to crash into each other. This created the highest energy particle collision at that time. The experiment showed that the charge of an electron is very, very small. O'Neill thought his device could only store particles for seconds. But by making an even stronger vacuum, others were able to store them for hours. He retired from teaching in 1985.

Living in Space: A Big Idea

How the Idea Started (1969)

O'Neill saw great potential in the U.S. space program. He especially liked the Apollo missions. He even tried to become an astronaut himself in 1966. When asked why he wanted to go to the Moon, he said it seemed wrong not to be a part of it. He went through tough tests from NASA. He met Brian O'Leary, another scientist trying to be an astronaut. They became good friends. O'Leary was chosen, but O'Neill was not.

O'Neill became interested in space colonization in 1969. He was teaching physics at Princeton. His students felt science wasn't helping humanity much because of the Vietnam War. To show them how science could help, he used examples from the Apollo program. He asked his students, "Is the surface of a planet really the right place for a growing technological civilization?" His students' research made him believe the answer was no.

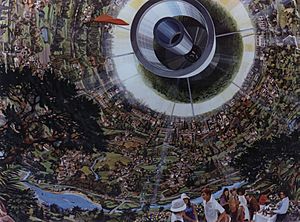

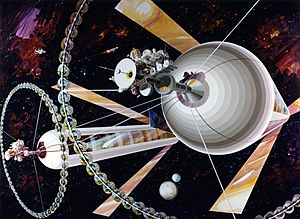

O'Neill was inspired by his students' ideas. He started working on plans to build self-supporting homes in space. He figured out how to give people in a space colony an Earth-like environment. His students had designed huge structures that would spin. This spinning would create a feeling of gravity, like on Earth. People would live on the inside surface of these spinning spheres or cylinders. These structures looked like "inside-out planets." He found that using two cylinders spinning in opposite directions would make them stable. This design is now known as the O'Neill cylinder.

Sharing the Idea (1970–1974)

O'Neill wrote a paper called "The Colonization of Space." He tried for four years to get it published. Many journals and magazines turned it down. During this time, O'Neill gave talks about space colonization. Many students and staff who heard him became excited about living in space. He also talked about his ideas with his children. They would imagine life in a space colony during walks in the forest. His paper finally came out in Physics Today in September 1974.

He thought about flying gliders inside a space colony. He realized the huge space could create air currents, like thermals on Earth. He calculated that humanity could grow to 20,000 times its current population in these man-made spaces. The first colonies would be built at special spots called Lagrange points (L4 and L5). These are stable points in the Solar System where a spacecraft can stay without using much fuel. The paper was well-received. But many people who would work on the project already knew his ideas before it was published. Some people did question if it was practical to send so many people into orbit.

While waiting for his paper to be published, O'Neill held a small meeting in May 1974. It was at Princeton and was about colonizing space. Many important people attended, including Eric Drexler and Freeman Dyson. NASA representatives also came. They shared how much it might cost to launch things with the new Space Shuttle. O'Neill thought of the attendees as "a band of daring radicals." A newspaper article about the meeting was on the front page of The New York Times. As more news spread, O'Neill got many letters from excited people. He started a mailing list to keep in touch. A few months later, he heard about solar power satellites. O'Neill realized that building these satellites could quickly pay for the space colonies. He said, "the profound difference between this and everything else done in space is the potential of generating large amounts of new wealth."

NASA Studies and Private Funding

O'Neill held a much bigger meeting in May 1975. It was called Princeton University Conference on Space Manufacturing. Many speakers presented their ideas.

In June 1975, O'Neill led a study at NASA Ames about permanent space homes. He also spoke to the U.S. House and Senate about his ideas. He explained his plan for building power plants in space. He returned to NASA Ames in 1976 and 1977 to lead more studies. In these studies, NASA made detailed plans to set up bases on the Moon. Workers there would mine minerals to build space colonies and solar power satellites.

Even though NASA gave him money, O'Neill felt frustrated by government rules. He thought small private groups could develop space technology faster. In 1977, O'Neill and his wife Tasha started the Space Studies Institute (SSI). It was a non-profit group at Princeton University. SSI got money from private donors. In 1978, it started supporting research for space manufacturing and settlement.

One of SSI's first projects was to fund the mass driver. O'Neill first suggested this device in 1974. Mass drivers are like a coilgun. They can speed up objects that are not magnetic. O'Neill thought mass drivers could throw baseball-sized chunks of moon rock into space. Once in space, this rock could be used to build space colonies and solar power satellites. He worked on mass drivers at MIT. There, he and Henry Kolm, with student helpers, built their first mass driver prototype. This prototype was eight feet long. It could speed up an object very quickly. With SSI's help, later versions were even faster. A mass driver only 520 feet long could launch material off the Moon's surface.

Challenges and Later Years

In 1977, interest in space colonization was at its highest. O'Neill's first book, The High Frontier, came out. He and his wife were very busy with meetings and interviews. A TV show called 60 Minutes featured space colonies. Later, Senator William Proxmire criticized the idea. He said, "not a penny for this nutty fantasy." He successfully stopped government money for space colonization research. When it became clear that the government would not fund a big colonization effort, public support for O'Neill's ideas began to fade.

Other problems for O'Neill's plan included the high cost of getting into Earth orbit. Also, the cost of energy went down. Building solar power stations in space seemed good when energy prices were high in 1979. But when prices dropped in the early 1980s, funding for space solar power research stopped. His plan also relied on NASA's hopeful estimates for the Space Shuttle's launch costs. These costs turned out to be much higher than expected.

In 1985, President Ronald Reagan appointed O'Neill to the National Commission on Space. This group suggested that the government should aim to open the inner Solar System for human settlement within 50 years. Their report came out in May 1986. This was four months after the Space Shuttle Challenger accident.

Writing and Inventions

O'Neill's popular science book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space (1977) mixed stories of space settlers with his plans for space colonies. This book made him the main spokesperson for the space colonization movement. It won an award and earned him an honorary degree. The High Frontier has been translated into five languages.

His 1981 book 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future looked into the future. O'Neill wrote it as if he was a visitor from a space colony beyond Pluto. The book explored how new technologies might change the next century. Some ideas he described were space colonies, solar power satellites, and hydrogen-powered cars.

In his 1983 book The Technology Edge, O'Neill wrote about economic competition. He said the U.S. needed to develop six key industries. These included robotics, genetic engineering, and space science.

New Companies and Ideas

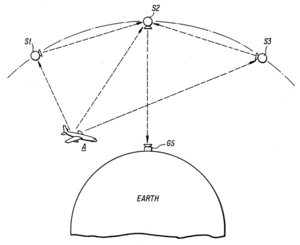

O'Neill started Geostar Corporation. This company aimed to create a satellite system to find positions. He got a patent for this system in 1982. It was mainly for tracking aircraft. Geostar launched a satellite in 1986. Its transmitter failed, so Geostar used other satellites for testing. As O'Neill's health declined, he became less involved. Geostar later went out of business. But O'Neill made important progress in finding positions using satellites.

In 1986, O'Neill founded O'Neill Communications. He introduced his Local Area Wireless Networking (LAWN) system in 1989. The LAWN system allowed two computers to share messages wirelessly. O'Neill Communications closed in 1993.

On November 18, 1991, O'Neill filed a patent for a super-fast train system. He called it Magnetic Flight. These vehicles would float above a single track using magnets. They would travel through tunnels with no air inside. He thought these trains could reach speeds of up to 2,500 miles per hour. This is about five times faster than a jet plane. O'Neill planned to build a network of stations connected by these tunnels. However, he passed away before his first patent on it was granted.

Death and Lasting Impact

O'Neill was diagnosed with leukemia in 1985. He died on April 27, 1992, from problems related to the disease. He was survived by his wife Tasha, his ex-wife Sylvia, and his four children. A small amount of his ashes was sent into space. His ashes were placed in a special container. This container was launched into Earth orbit on a Pegasus XL rocket on April 21, 1997. It re-entered the atmosphere in May 2002.

O'Neill wanted his Space Studies Institute to keep working "until people are living and working in space." After he died, his son Roger and friend Freeman Dyson took over. The SSI continued to hold meetings about space colonization until 2001.

O'Neill's work inspires the company Blue Origin, started by Jeff Bezos. Blue Origin wants to build the tools for future space colonization.

Henry Kolm later started a company called Magplane Technology. It develops the magnetic transportation technology O'Neill wrote about. In 2007, Magplane showed a working magnetic pipeline system. It moved phosphate ore at 40 miles per hour. This was slower than O'Neill's vision, but still a step forward.

The National Space Society (NSS) gives the Gerard K. O'Neill Memorial Award. This award honors people who have helped with space settlement. The award is a trophy shaped like a Bernal sphere. The NSS first gave this award in 2007 to former astronaut Harrison Schmitt.

As of November 2013, Gerard O'Neill's papers and work are kept in the archives at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Patents

O'Neill received six patents. Two of them were granted after he passed away. These patents were for global position finding and magnetic levitation.

- , US 4359733 Satellite-based vehicle position determining system, granted November 16, 1982

- , US 4744083 Satellite-based position determining and message transfer system with monitoring of link quality, granted May 10, 1988

- , US 4839656 Position determination and message transfer system employing satellites and stored terrain map, granted June 13, 1989

- , US 4965586 Position determination and message transfer system employing satellites and stored terrain map, granted October 23, 1990

- , US 5282424 High speed transport system, granted February 1, 1994

- , US 5433155 High speed transport system, granted July 18, 1995

See also

In Spanish: Gerard K. O'Neill para niños

In Spanish: Gerard K. O'Neill para niños

- Konstantin Tsiolkovskii (1857–1935) wrote about humans living in space in the 1920s

- J. D. Bernal (1901–1971) inventor of the Bernal sphere, a space habitat design

- Rolf Wideröe (1902–1996) filed for a patent on a particle storage ring design during World War II

- Krafft Ehricke (1917–1984) rocket engineer and space colonization advocate

- John S. Lewis, wrote about the resources of the Solar System in Mining the Sky

- Marshall Savage, author of The Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy Steps

- Spome

- Space architecture

- Space-based solar power

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |