Grace Raymond Hebard facts for kids

Grace Raymond Hebard (born July 2, 1861 – died October 1936) was an important person in Wyoming history. She was a historian, a suffragist (someone who fought for women's right to vote), a scholar, a writer, and a professor at the University of Wyoming. Hebard became known as a historian because she traveled all over Wyoming. She explored its plains and mountains to find stories from early pioneers. Today, some people question her history books. This is because she sometimes made the Old West sound more exciting than it was. For example, her idea that Sacajawea (who helped the Lewis and Clark Expedition) was buried in Wyoming is still debated.

Hebard was also the first woman on the University of Wyoming Board of Trustees. This meant she helped manage the university's money, its president, and its teachers. She also started the university's first library. Plus, Hebard taught as a professor for 28 years. She was the first woman allowed to be a lawyer in Wyoming in 1898. Later, she could argue cases in front of the Wyoming Supreme Court. Her fellow lawyers also chose her as vice president of the National Society of Women Lawyers.

She was very active in Wyoming's government and community. She gave speeches, helped create history groups, and taught classes for immigrants to become citizens. She also worked with the local and national movement for women's right to vote. Hebard helped create laws to protect children. During World War I, she volunteered for the Red Cross and sold war bonds to help the country.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Grace Hebard was born in Clinton, Iowa, on July 2, 1861. Her parents were Rev. George Diah Alonzo Hebard and Margaret E. Dominick Hebard. Her family soon moved to Iowa City. There, her father, a missionary, built a new church. Grace studied civil engineering at the University of Iowa and earned her degree in 1882. She was a member of the Pi Beta Phi Women's Fraternity. She was the first woman to graduate from the Civil Engineering Department at the University of Iowa.

Hebard later wrote about her time as a female engineering student in 1928. She said, "I faced many challenges and much opposition to studying science. It was a men's college back then. People said I would fail and that a woman couldn't do that kind of work."

Hebard continued her studies by mail and earned a master's degree from the University of Iowa in 1885. She then received her Ph.D. in political science from Illinois Wesleyan University in 1893, also through correspondence.

Moving West to Wyoming

In 1882, Hebard moved west to Cheyenne, Wyoming. This was eight years before Wyoming became a state in 1890. She arrived with her mother and siblings. She became part of the social life in Cheyenne. She found work at the surveyor general's office. She was the only female draftsman in the city. Hebard became the deputy state engineer. She worked under Elwood Mead, who helped write Wyoming's water laws.

However, engineering was not her main path. After nine years in Cheyenne, she moved to Laramie, Wyoming in 1891. Laramie was a small railroad town with a new university. Hebard spent more than 45 years (1891–1936) at the University of Wyoming.

Leading the University

In 1891, Grace Hebard was appointed as a secretary and member of the University of Wyoming Board of Trustees. She was 30 years old and entered a world mostly run by men. She quickly learned that leading a university would have its challenges. Hebard used her position with great power, serving until 1903 and as secretary until 1908. She had a strong influence on the university for 17 years.

She helped set university rules and managed its money. Hebard controlled the university's finances almost completely. She once said, "The Trustees gave me a great deal of power, and I used it."

The university faced money problems in the mid-1890s. In 1894, Wyoming had only six high schools, and just eight students graduated from them. This made it hard for the university to find new students. The university also relied on money from the government for its Agricultural Experiment Station. Hebard became very important in this part of the university too.

Hebard had a lot of power over the university's money, its president, and its teachers. Some people even said that conflicts with Hebard caused President A. A. Johnson to resign. Her strong control often came from her power over money, including government grants. There were questions about how federal money was being used. This led to more attention on the Board of Trustees.

In 1907, some newspapers criticized Hebard's power. They claimed there were problems with university contracts and spending. One newspaper said that no one at the university could keep their job without her approval. However, an investigation found that Hebard had not done anything wrong. Still, because of the criticism, Hebard resigned as secretary to the trustees.

Even after stepping down from her administrative role in 1908, Hebard began a new phase of her career. She became a full professor at the same university. She held this teaching position for 28 years until she passed away.

Writer and Historian

Grace Hebard also became the university's first librarian. She started this job without pay in 1894. She created a library from "sacks of books" she found in a small room. In 1908, she was officially named the university's first librarian. She continued as librarian until 1919. By the end of her time, the library had grown to 42,000 books. In 1906, Hebard also became the head of the Department of Political Economy.

Hebard joined an advisory board for the Wyoming Historical Association. This helped her start new research. She began marking trails in Wyoming, especially the Oregon Trail and other pioneer routes. She mapped old trails and collected historical documents about Wyoming.

She also traveled across the state, interviewing pioneers from the Old West. She spent several summers with the Shoshone Indians in Wyoming. Before she died in 1936, Hebard gave her collection of papers to the University of Wyoming. These papers included her maps, writings, and field notes. Her books about Wyoming history often showed a romantic view of the Old West. Her published books include:

- The Government of Wyoming (1904)

- The Pathbreakers from River to Ocean (1911)

- The Bozeman Trail (1922), co-authored with E.A. Brinninstool

- Washakie (1930)

- Sacajawea (1933)

Hebard was working on a book about the Pony Express when she became ill and passed away. The famous photographer William Henry Jackson helped her with illustrations for this unfinished book in 1933 and 1934.

Understanding History

The American frontier was officially declared "closed" in 1890. But for Grace Hebard, the history of the West was still wide open for her to explore. She often presented her research subjects in a very exciting and "romanticized" way.

Some critics say that Hebard's histories led to many stories about Wyoming's past that might not be true. They say that sometimes when facts didn't support her ideas, she created her own "facts."

One example is her 1933 book about Sacajawea, the Shoshone woman who helped the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Hebard spent 30 years researching this book. Critics question her findings because the book is "long on romance and short on hard evidence."

Hebard described Sacajawea as a brave woman who traveled widely. According to stories Hebard collected, Sacajawea was so respected by white people that she rode stagecoaches for free. Hebard also wrote that Sacajawea helped the Shoshones learn to farm.

Hebard visited Sacajawea's reported grave in Wyoming in 1915. She wrote, "Thousands of people journey to this last resting place." However, many historians today believe Hebard might have confused Sacajawea with another person.

Despite these questions, Hebard believed her research proved Sacajawea's true identity. She even shared a "secret" with her friend Agnes Wright Spring shortly before her death. Hebard said that the Native Americans on the Wind River Reservation gave her a special name: Zont-Tumah-Two-Wiper-Hinze. This meant "the good white woman, the woman with one tongue." She believed this showed they felt she was telling the truth about their ancestor.

Historian Phil Roberts says that Grace Hebard is still important. He notes that she wanted to record Wyoming's history while the people who lived it were still alive. Hebard faced challenges because there weren't always reliable sources. This sometimes led to assumptions that might not match historical records.

Trail Blazer and Preserver

Grace Hebard loved marking, saving, and remembering the quickly changing frontier. She helped start groups like the Wyoming Oregon Trail Commission. She also worked with the Wyoming Historical Association and the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.). As the state historian for the D.A.R., she helped put up and dedicate historical markers. These markers were placed at important sites across Wyoming. This included famous Oregon Trail landmarks like Fort Laramie and Independence Rock. She also marked less known sites on the Bozeman Trail and the Pony Express route.

Hebard was always busy. In the summers, she often traveled across Wyoming's rangelands. Sometimes she used a horse and wagon, and later an automobile. She searched for old Oregon Trail ruts or looked for historic sites. She also interviewed pioneers. She even used snowshoes to explore in the winter. Summer trips could be hard too. Heavy rains could turn dirt roads into deep mud.

Hebard traveled about 800 miles with a team of horses in the summers of 1913 and 1914. She noted the "much inconvenience and hardship" due to frequent rains, strong winds, deep dust, and mosquitoes. She often had to camp away from streams because of the insects.

Hebard especially recognized the work of H.G. Nickerson, a Civil War veteran. Nickerson had lived in the South Pass area since 1868. He later became president of the Oregon Trail Commission of Wyoming. Hebard praised his work in finding and marking old western trails for eight years. She noted that Nickerson carved inscriptions on stones and boulders he placed in the open country.

Marking trails often meant going to remote places. But Wyoming's isolated areas did not stop Hebard and the Daughters of the American Revolution from holding formal ceremonies. These events included music, prayers, patriotic songs, and speeches. Stone markers placed by Nickerson, Ezra Meeker, Hebard, and others are still found across Wyoming. They are important reminders of the state's early efforts to preserve history.

Helping New Americans

Grace Hebard reportedly valued her work helping immigrants become Americans the most. A newspaper in 1935 said that her "certificates of preparation for naturalization were accepted by the United States District Court instead of citizenship exams." This shows how much influence she had.

Hebard's work helping new Americans began in 1916. She believed that immigrants could learn and fit into American culture. This was during a time when many immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe were coming to the United States.

Hebard's work with immigrants in Laramie was different from some of the tensions happening across the country. She helped people learn about their new country and become citizens.

Hebard's activism often went against common ideas in Wyoming and the nation. Her life, including her close friendship with fellow Professor Agnes Wergeland, showed her beliefs. Wergeland, like Hebard, was a trailblazer. She was the first woman from Norway to earn a Ph.D. Hebard helped Wergeland understand what it meant for women to have the right to vote in Wyoming.

Fighting for Women's Vote

Wyoming was a leader in women's rights. On December 10, 1869, the governor signed a law giving women the right to vote. This made national suffragists very happy. Grace Hebard was a strong supporter of women's suffrage. In a 1920 interview, she said that in Wyoming, where women had voted for 50 years, there was no opposition to women's suffrage.

Because of this, Esther Hobart Morris made history in Wyoming in 1870. She became the nation's first female justice of the peace. This happened in South Pass City after the previous justice resigned to protest the suffrage law. Hebard believed that Morris helped write that law. However, some recent researchers say this claim is not true.

Hebard and Nickerson put up a stone monument near Morris's cabin in 1920 to remember her. Later, a granite marker replaced it. The Wyoming Division of State Parks and Historic Sites has tried to correct the record. They say that William H. Bright was the only author of the suffrage bill.

Wyoming was the first western territory or state to give women the right to vote. This put Wyoming in the national spotlight. National suffragists used Wyoming as an example as states voted on the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote across the U.S.

Carrie Chapman Catt, who led the National American Woman Suffrage Association, praised Wyoming. She said Wyoming showed how much good came from women voting.

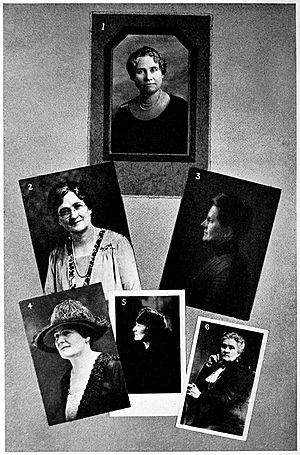

Hebard herself played a big part in the suffrage movement. She asked the Wyoming constitutional convention to include a suffrage clause before Wyoming became a state in 1890. National suffragists also asked Hebard to join the National American Woman Suffrage Association. She was also part of the Suffrage Emergency Brigade, which worked to get Connecticut to be the 36th state to approve the 19th Amendment. Hebard was one of the few people who spoke at the 1920 suffrage celebration in Chicago after the Nineteenth Amendment passed.

Hebard also worked with Carrie Chapman Catt to get the University of Wyoming's first honorary degree awarded to Catt in 1921. Catt came to Laramie to receive the honor and give a speech. This event highlighted Laramie's history as a place where women first voted and served on a jury.

Later Years and Legacy

Grace Hebard retired from teaching in 1931. But she kept researching and collecting historical items at her home in Laramie, known as "The Doctors' Inn." She had built this house with her friend, Agnes Wergeland, who passed away in 1914. Grace's sister, Alice Marvin Hebard, lived there until her death in 1928.

Hebard died in October 1936 at 75 years old. She was a very strong and influential person at the university until her death. The University of Wyoming held a memorial for her that month. Many important people attended her funeral and contributed to a special "In Memoriam" program.

The memorial service included tributes from:

- Mr. and Mrs. Bryant Butler Brooks, former Wyoming governor

- Robert D. Carey, United States senator and former Wyoming governor

- Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association

- Frank Pierrepont Graves, president of the University of the State of New York

- W. H. Jackson, pioneer photographer

- Agnes Wright Spring, former Wyoming State Historian

These tributes described Hebard as a strong, active woman who loved history and marking trails. She was also recognized as the first woman admitted to the Wyoming State Bar Association (1898). She was also allowed to practice law before the Wyoming Supreme Court (1914). Her friends and colleagues also noted her involvement in many community activities. She supported American troops in World War I by selling war bonds and planting Victory Gardens. She also helped pass a child labor law in Wyoming in 1923.

Young people, especially University of Wyoming students, were very important to Hebard. University President Crane said, "Above all she was a friend to generations of students." The student newspaper also wrote that students had lost a friend when she died.

Hebard also helped students by funding several scholarships, including:

- The Agnes Mathilde Wergeland Memorial History Scholarship

- The Alice Marven Hebard Memorial Fund

- Hebard Map Scholarship Fund

Grace Hebard is buried in Greenhill Cemetery in Laramie, near her sister Alice and Agnes Wergeland. A plaque honoring Hebard is on Independence Rock, a famous Oregon Trail landmark in central Wyoming.

See also

- Ezra Meeker

- Esther Hobart Morris

- List of first women lawyers and judges in Wyoming

- History of women's suffrage in the United States

- Oregon Trail

- Sacajawea

- University of Wyoming

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |