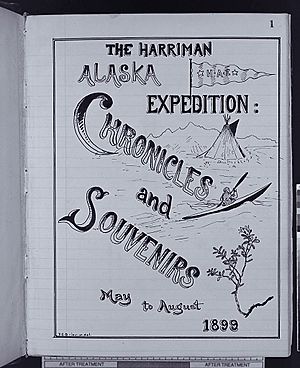

Harriman Alaska expedition facts for kids

The Harriman Alaska Expedition was an amazing journey that explored the coast of Alaska. It lasted two months in 1899. The trip started in Seattle, went all the way to Alaska and even Siberia, and then returned. A very rich railroad owner named Edward Harriman organized it. He invited many top scientists, artists, photographers, and naturalists to join him. Their goal was to explore and record everything about the Alaskan coast.

Contents

Why the Journey Started

Edward Harriman was one of the most powerful people in America. He owned many railroads. By 1899, he was very tired. His doctor told him he needed a long break. So, Harriman decided to go to Alaska to hunt Kodiak bears.

Instead of going alone, he chose to bring a team of experts. He wanted them to explore and document the Alaskan coast. He contacted Clinton Hart Merriam. Merriam was a leader in studying birds and mammals for the U.S. government. Harriman told Merriam he would pay for all the scientists, artists, and other experts. He asked Merriam to pick the best team for the trip.

People wondered why Harriman wanted to go to Alaska. Some thought he wanted to develop Alaska's resources. Others thought he might build a railroad there. Some even joked he might buy Alaska or build a railroad bridge to Siberia. For Edward H. Harriman, anything seemed possible!

Merriam quickly got to work. He sent many telegrams and held meetings. He put together a wide range of experts. These included arctic experts, botanists (plant scientists), biologists (life scientists), zoologists (animal scientists), geologists (rock and earth scientists), geographers (landform scientists), artists, photographers, ornithologists (bird scientists), and writers.

Harriman had his steamship, the SS George W. Elder, specially prepared. The ship was changed to have lecture rooms and a library. It had over 500 books about Alaska. There were also studios for taxidermy (preparing animal specimens). The team had luxury rooms. Some people on the trip called the ship the George W. Roller. This was because it often rocked a lot, making passengers seasick.

Who Went on the Expedition

The team included many of the best American scientists, artists, and photographers of that time. They came from many different fields.

Arctic Experts

- William Brewer, a naturalist (someone who studies nature)

- John Muir, a naturalist

- William Dall, a paleontologist (studies fossils) and geographer

Botanists (Plant Scientists)

- Frederick Coville, botanist

- Thomas Kearney, botanist

- De Alton Saunders, botanist

- William Trelease, botanist

- Bernhard Fernow, forester (studies forests)

Biologists and Zoologists (Life and Animal Scientists)

- Wesley Coe, biologist

- W. B. Ritter, Ph.D., biologist

- Daniel Elliot, zoologist

- Clinton Hart Merriam, zoologist

- William Emerson Ritter, biologist

- Trevor Kincaid, entomologist (studies insects)

- A. K. Fisher, ornithologist (studies birds)

- Charles Keeler, ornithologist

- Robert Ridgway, ornithologist

- William H. Averell

- Leon J. Cole, ornithologist

Geologists and Geographers (Earth and Landform Scientists)

- W. B. Devereux, mining engineer

- Benjamin Emerson, geologist

2 Henry Gannett, geographer

- Grove Karl Gilbert, geologist

- Charles Palache, geologist

Artists and Photographers

- Edward Curtis, photographer

- Frederick Dellenbaugh, artist

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes, bird artist

- R. Swain Gifford, artist

- D. G. Inverarity, photographer (Curtis’ assistant)

Writers

- George Bird Grinnell, expert on Native American culture

- John Burroughs, author

Harriman also brought a medical team and a chaplain. There were hunters, guides, and taxidermists. He even brought his own family and servants. With the ship's crew, there were 126 people on board in total.

The Voyage Journey

By the end of May, everyone had arrived in Seattle. Newspapers worldwide wrote about the trip. The Elder left Seattle on May 31, 1899. Cheering crowds waved goodbye.

Their first stop was the Victoria Museum on Vancouver Island. Then they traveled north to Lowe Inlet. There, they stopped to explore and record the wildlife.

On June 4, they stopped in Metlakatla. This was a European-style town created by a Scottish missionary, William Duncan. He made it for the Alaskan Native people. The scientists visited Duncan at his home.

Over the next two weeks, the Elder stopped at several places in Alaska. These included Skagway and Sitka. They saw the good and bad effects of the Klondike Gold Rush. They kept cataloging plants, animals, and sea creatures. They also studied geological and glacial formations. Harriman had brought a recording machine. He used it to record a Native Tlingit song.

By June 25, they reached Prince William Sound. They found a fjord (a long, narrow inlet of the sea) that wasn't on any maps. They named it "Harriman Fjord."

The scientists had some say in where they stopped. But Harriman always had the final decision. He really wanted to hunt a bear. So, he decided to go towards Kodiak Island when he heard bears were there.

On July 7, they reached Popof Island in the Shumagin Islands. Four scientists decided to camp there. This allowed them to make very detailed notes. The rest of the team continued on to Siberia.

Edward Harriman’s wife wanted to visit Siberia. So, the Elder kept sailing north. By July 11, the ship arrived at Plover Bay in Siberia.

By this time, Harriman was eager to get back to work. The Elder sailed south. It picked up the team from Popof Island. On July 26, the Elder made one last stop. It was at an abandoned Tlingit village at Cape Fox. On July 30, the ship finally arrived back in Seattle.

Books from the Expedition

Harriman paid for several large books about the expedition's discoveries. When Harriman died in 1909, his wife gave more money to continue the publications. Merriam was the editor. He spent twelve years working on these books.

John Burroughs, a famous nature writer, was the official writer for the expedition. He wrote much of Volume I, which was a general overview of the trip. Volumes VI and VII, which were supposed to be about mammals, were never published. Maybe Merriam was too busy with his other work. Other scientists from the expedition or authors hired by Merriam wrote later volumes. While they often mentioned Alaska's beauty, the books were mostly very technical. They were written for other scientists.

The first book was published in 1901. More books came out in the following years. The Smithsonian republished the whole series in 1910. You can now download these books for free.

What the Expedition Achieved

The expedition claimed to have found about 600 species new to science. This included 38 new fossil species. They mapped where many species lived. They discovered an unmapped fjord and named several glaciers. Gilbert’s work on glaciers brought new ideas to that field.

Another important result of the trip was the career of Edward Curtis. On the journey, he became good friends with George Bird Grinnell. Grinnell was an expert on Native American culture. After the expedition, Grinnell invited Curtis to visit the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana. Curtis was deeply moved by what he saw. He believed this way of life was disappearing. So, he spent much of his career documenting Native American culture.

At first, John Muir didn't like Harriman. He thought Harriman's hunting was cruel. But during and after the trip, they became friends. Years later, Muir asked Harriman to help lobby the government for National Park laws. John Muir even gave the speech at Harriman’s funeral in 1909.

The expedition showed a mix of old and new scientific ideas. It often showed the best of new 20th-century science. But it also showed how scientists thought in the 19th century.

They were ahead of their time by working as a truly interdisciplinary team. This means experts from many different fields worked together. Having so many different experts helped them solve many parts of the puzzle. They also talked about the possible loss of wilderness and Native peoples. They saw the effects of the Yukon gold rush. They saw how treasure hunters were harming the land and the Native cultures.

However, in many ways, their science was still rooted in the 19th century. Back then, scientists often wrote very long descriptions of plants or animals. Most of the expedition's books followed this style. This way of studying biology changed in the early 20th century.

Another example of 19th-century thinking was their view of Native cultures. They saw Native people as "savages." While they were horrified that Native cultures were disappearing, they also thought that adopting European ways would help them.

Even among the expedition members, there were different opinions. When they saw Native peoples working in salmon fishing and canning factories, people on the Elder felt different things. Some saw the cannery work as forced labor, like slavery. Other members thought the canneries were efficient and good.

Cape Fox Artifacts and Their Return

On July 26, 1899, the expedition landed at Cape Fox. This was an abandoned Tlingit village. The village had been empty for about five years. But many Tlingit artworks and totem poles were still there. Some expedition members removed some of these items. Other members protested this.

This act has been called "looting" by some. But it's important to understand the thinking at the time. Expedition members believed that Alaska's Native cultures would soon disappear. They thought modern civilization would take over. Their goal was to save these items in museums. They believed these would be the last pieces of Tlingit art and culture. The expedition members saw the items as objects from an empty village. But for the Tlingit people living nearby, these items were sacred. They were a part of their identity.

The Cape Fox artifacts were indeed kept in museums. In 2001, a group of scientists followed the path of the 1899 Harriman Expedition. This 2001 team included Edward Harriman's great-great-granddaughter. They returned many of the artifacts to the descendants of the original Cape Fox Tlingit residents.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |