Henry Lincoln Johnson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Lincoln Johnson

|

|

|---|---|

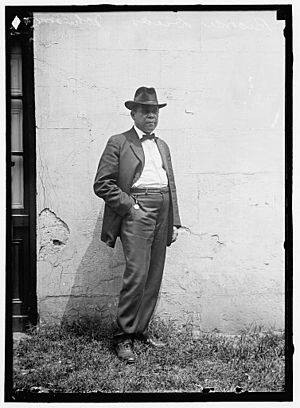

Johnson in 1914 in Washington

|

|

| Washington DC Recorder of Deeds | |

| In office 1909–1913 |

|

| Appointed by | William Howard Taft |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 27, 1870 Augusta, Georgia |

| Died | September 10, 1925 (aged 55) Freedmen's Hospital Washington, D.C. |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Henry Lincoln Johnson, Jr. Peter Douglas Johnson |

| Parents | Martha Ann Peter Johnson |

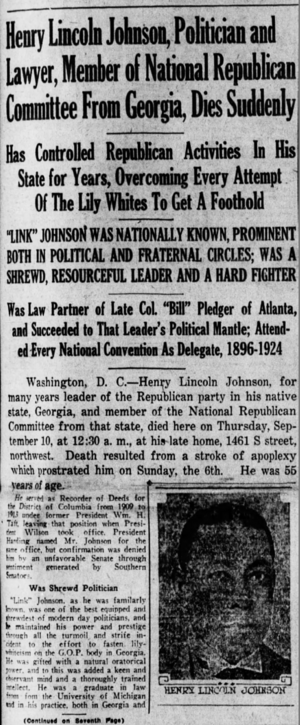

Henry Lincoln "Linc" Johnson (July 27, 1870 – September 10, 1925) was an American lawyer and politician from Georgia. He was a very important African-American leader in the Republican Party in the early 1900s. He led a group called the "black-and-tan faction" of the Republican Party of Georgia.

President William Howard Taft chose him for a special job in Washington, D.C.. This job was called the Recorder of Deeds. It was seen as a top political position for black Americans at that time. He was one of four people known as Taft's "Black Cabinet."

Later, President Warren G. Harding also tried to appoint Johnson to the same job in 1921. However, the United States Senate did not approve his appointment. This was mainly because two Democratic senators from Georgia opposed him. This event was big news and ended Johnson's national political influence.

After this, Johnson went back to being a lawyer in Washington, D.C. He passed away on September 10, 1925, after having a stroke at his home.

Contents

Henry Lincoln Johnson's Early Life and Education

Henry Lincoln Johnson, often called "Linc," was born on July 27, 1870. His birthplace was Augusta, Georgia. His parents, Martha Ann and Peter Johnson, were formerly enslaved people. They strongly believed in the importance of education.

Johnson attended Atlanta University, a college for black students. He graduated from there in 1888. Because of segregation laws in the South, he could not attend law schools there. So, he traveled north to the University of Michigan. He earned his law degree in 1892.

After passing the Georgia bar exam, Johnson started his own law practice in Atlanta. He later became the main lawyer for the Atlanta Life Insurance Company. This was a large business owned by black people.

In 1903, Johnson married Georgia Douglas. She was also a graduate of what is now Clark Atlanta University. She became a famous poet during the Harlem Renaissance. Henry and Georgia had two sons: Peter Douglas Johnson and Henry Lincoln Johnson, Jr.. Their son, Henry Jr., also became a well-known lawyer.

A Leader in Politics

Henry Lincoln Johnson became a powerful leader in Georgia's Republican politics. This was in the early 1900s. He was known for giving out political favors, also called "patronage." These favors went to black Republicans in the state.

At this time, it was becoming harder for black voters to choose their own representatives. Laws passed by white Democrats in Georgia limited their voting rights. Even so, black people remained loyal to the Republican Party. A journalist once described Johnson as a "tall figure" who spoke with strong and clear words.

In 1910, President William Howard Taft appointed Johnson as the Recorder of Deeds for Washington, D.C.. This was a very important job. It had often been given to African Americans since the Civil War. Johnson and his family then moved from Atlanta to Washington, D.C. for this new role.

Johnson was part of what was called Taft's "Black Cabinet." This group included other important black appointees. They were James Carroll Napier, Robert Heberton Terrell, and William H. Lewis.

Some people believe Johnson quietly supported the election of Southern Democrat Woodrow Wilson in 1912. Other black leaders, like W. E. B. Du Bois of the NAACP, also did this. They were unhappy with the Republican Party's actions on issues important to them.

When Wilson became president, he removed many African Americans and other Republicans from their government jobs. This was a common practice when a new president from a different party took office. Even more, Wilson's administration segregated federal offices, lunchrooms, and restrooms. This meant black and white workers were separated for the first time. In 1914, job applications started requiring photos. This was a way to avoid hiring black people. Many African-American federal workers faced unfair treatment.

Johnson was criticized by a black socialist magazine called The Messenger. They said he was an example of politicians who profited from the hard work of black people.

During the 1916 and 1920 presidential elections, there were two main groups in the Republican Party of Georgia. One group was the "black and tans," led by Johnson. This group was mostly African American. The other group was the "lily whites," who were mostly European American. Johnson kept control of the party in Georgia during these years. This meant he controlled who got federal jobs in Georgia.

In 1920, Johnson helped create the Lincoln League in Chicago. This group wanted the Republican Party to take a strong stand against lynching and Jim Crow laws. These laws enforced racial segregation and took away voting rights from black people. Johnson got promises that the Republican Party would do more if they won the White House.

Johnson was also chosen to represent Georgia on the Republican National Committee in 1920. This decision caused some debate. However, the full Republican convention approved Johnson's selection. This helped the Republicans keep black voters outside the South.

A Nomination That Failed

The Republican Party did very well in the 1920 Presidential election. This made Johnson's position stronger. However, the disagreement between Johnson's "black and tans" and the "lily whites" in Georgia grew. Both groups wanted influence with the new President, Warren G. Harding. They both wanted to control federal jobs in Georgia.

President Harding tried to fix this problem by reorganizing the Republican Party in Georgia. He called five Georgia business leaders to the White House in April 1921. He asked them to see if business people would support a new Georgia Republican Party.

The "lily whites" liked Harding's plan. They thought it would help white leaders gain control. Johnson, however, had the most to lose and opposed it. Eventually, Johnson was convinced to leave the fight in Georgia politics. He was offered the job of Registrar of Deeds for Washington, D.C. again by President Harding.

After Johnson was appointed and moved to Washington in June 1921, the Georgia Republican Party was reorganized. This happened on July 26, 1921, with a group of mostly white business leaders.

Johnson's appointment needed to be approved by the United States Senate. In November 1921, Georgia's Democratic Senator Tom Watson strongly opposed Johnson. Watson was a political enemy and supported white supremacy. He said Johnson's appointment was "personally obnoxious to him." This was a special phrase used in the Senate. It meant a senator could block an appointment for their state.

Georgia's other Senator, Nathaniel Edwin Harris, also said Johnson was "personally obnoxious." Because of these objections, almost all senators voted against Johnson's appointment. Only one senator voted for him. This rejection ended Johnson's national political career.

Later Life and Lasting Impact

After his Senate rejection in 1921, Johnson returned to his law practice in Washington, D.C. His role in national politics became smaller. One of his most famous cases was in 1922. He defended a young black man who faced a very long prison sentence or even execution. The young man was also in danger of being lynched.

Johnson was very skilled in questioning witnesses. He gave a powerful closing argument in the court. The jury could not agree on a verdict after six hours. Seven jurors voted for the young man to be found not guilty. The jury foreman later said that Johnson's speech saved the defendant's life.

Even though he was no longer a major figure in Georgia politics, Johnson was not forgotten. In September 1923, President Calvin Coolidge invited Johnson and other black political leaders to Washington, D.C. They met to discuss issues important to the African-American community. They continued to seek more national support to end unfair treatment in the South.

Henry Lincoln Johnson passed away on September 10, 1925. He died at Freedmen's Hospital in Washington, D.C., after having a stroke at home. He was 55 years old. He was buried at Columbian Harmony Cemetery. Later, in 1959, his remains were moved to National Harmony Memorial Park Cemetery.

After his death, the Pittsburgh Courier, an important black newspaper, wrote about him. They said that Johnson was always focused on politics. He worked tirelessly for his group and cared little for his own comfort. They described him as a unique person, admired and sometimes disliked, but always true to himself.

Works by Henry Lincoln Johnson

- The Negro Under Wilson. Washington, D.C.: Republican National Committee, n.d. [1916?].

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |