Puyi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Xuantong Emperor宣統 |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huangdi 皇帝 | |||||||||||||||

Puyi c. 1930–40s

|

|||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||

| First reign | 2 December 1908 – 12 February 1912 | ||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Guangxu Emperor | ||||||||||||||

| Successor | monarchy abolished; Yuan Shikai as president | ||||||||||||||

| Regents | Zaifeng, Prince Chun (1908–11) Empress Dowager Longyu (1911–12) |

||||||||||||||

| Prime Ministers |

|

||||||||||||||

| Second reign | 1 July 1917 – 12 July 1917 | ||||||||||||||

| Prime minister | Zhang Xun | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor of Manchukuo | |||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1 March 1934 – 17 August 1945 | ||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Himself as Chief Executive of Manchukuo | ||||||||||||||

| Successor | Position abolished (Manchukuo dissolved) | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister |

|

||||||||||||||

| Chief Executive of Manchukuo | |||||||||||||||

| Reign | 18 February 1932 – 28 February 1934 | ||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Manchukuo and position established | ||||||||||||||

| Successor | Himself as emperor | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Zheng Xiaoxu | ||||||||||||||

| Born | Aisin-Gioro Puyi (愛新覺羅·溥儀) February 7, 1906 Prince Chun Mansion, Beijing, Qing China |

||||||||||||||

| Died | October 17, 1967 (aged 61) Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, People's Republic of China |

||||||||||||||

| Burial | Hualong Imperial Cemetery, Yi County, Hebei | ||||||||||||||

| Consorts |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| House | Aisin Gioro | ||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Qing (1908–1912, 1917) Manchukuo (1932–1945) |

||||||||||||||

| Father | Zaifeng, Prince Chun of the First Rank | ||||||||||||||

| Mother | Gūwalgiya Youlan | ||||||||||||||

| Seal |  |

||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 溥儀 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 溥仪 | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Xuantong Emperor | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 宣統帝 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 宣统帝 | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (Chinese: 溥儀; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967) was the last emperor of China. He was the eleventh and final ruler of the Qing dynasty.

Contents

Puyi: China's Last Emperor

Early Life and Becoming Emperor

Puyi became emperor when he was only two years old in 1908. He grew up used to getting everything he wanted. The adults around him, except for his nurse, were strangers. They couldn't tell him what to do. Wherever he went, grown men would kneel down in a special bow called a kowtow. They would look away until he passed.

Puyi soon learned he had great power over the palace servants, called eunuchs. He often had them punished for small mistakes. As emperor, Puyi's every wish was granted. No one ever said no to him. He later said that his "cruelty and love of wielding power were already too firmly set."

Puyi received a traditional Confucian education. He learned about Chinese classics but nothing else. He later wrote that he learned "nothing of mathematics, let alone science." He didn't even know where Peking was located for a long time. When he was 13, he met his parents and siblings. They all had to kowtow to him. He had forgotten what his mother looked like.

His younger brother, Pujie, never heard his parents call Puyi "your elder brother." They only called him "the emperor." Puyi lived a very isolated childhood in the Forbidden City. He was surrounded by guards and servants who treated him like a god. His upbringing was a mix of being spoiled and being treated strictly. He had to follow all the rules of the imperial palace. He couldn't act like a normal child.

The eunuchs were like slaves who did all the work in the Forbidden City. This included cooking, gardening, and cleaning. They also helped with the government work. The Forbidden City was full of treasures. The eunuchs often stole these and sold them.

Puyi never had any privacy. Eunuchs opened doors for him, dressed him, and washed him. They even blew air into his soup to cool it. At meals, he had a huge buffet of many dishes, but he ate very little. Every day he wore new clothes, as emperors never wore the same clothes twice.

Losing the Throne: Abdication

On October 10, 1911, soldiers in Wuhan started a revolt. This sparked a big uprising across China. People wanted to overthrow the Qing dynasty, which had ruled since 1644. General Yuan Shikai was sent to stop the revolution. But he couldn't, because many Chinese people no longer supported the Qing rulers.

Puyi's father, Prince Chun, was a regent until December 6, 1911. Then Empress Dowager Longyu took over after the Xinhai Revolution. On February 12, 1912, Empress Dowager Longyu agreed to the "Imperial Edict of the Abdication of the Qing Emperor." This deal was made by Yuan Shikai, who was now the Prime Minister.

Under this agreement, Puyi kept his imperial title. The new Republic of China treated him like a foreign king. Puyi and his court could stay in the northern part of the Forbidden City. They also had the Summer Palace. The Republic promised them a large annual payment, but it was rarely fully paid. It was stopped after a few years.

Puyi himself didn't know his reign had ended in February 1912. He still thought he was emperor for some time. In 1913, when Empress Dowager Longyu died, President Yuan came to the Forbidden City. Puyi's teachers told him this meant big changes were coming. Puyi soon learned that President Yuan wanted to become emperor himself. Yuan wanted Puyi to be a temporary caretaker of the Forbidden City.

A Brief Return to Power

In 1917, a warlord named Zhang Xun put Puyi back on the throne. This lasted only from July 1 to July 12. Zhang Xun ordered his soldiers to keep their traditional long braids (queues) to show loyalty to the emperor.

However, the Premier of the Republic of China, Duan Qirui, sent a plane to drop bombs over the Forbidden City. This was a show of force against Zhang Xun. One eunuch died, but the damage was minor. This was the first time a Chinese Air Force plane dropped bombs. The attempt to restore Puyi failed because most people in China were against it.

Life in Tianjin

In February 1925, Puyi moved to the Japanese area of Tianjin. He first lived in the Chang Garden and then in the Garden of Serenity in 1929. During this time, Puyi and his advisors talked about plans to make him emperor again. Some advisors wanted help from other countries, while others disagreed.

In June 1925, a warlord named Zhang Zuolin visited Puyi in Tianjin. Zhang ruled Manchuria, a large and industrial region. He bowed to Puyi and promised to restore the Qing dynasty if Puyi gave money to his army. Zhang warned Puyi not to trust his Japanese friends.

Ruler of Manchukuo

In September 1931, Puyi wrote to the Japanese Minister of War. He said he wanted to be emperor again. On September 18, 1931, the Mukden Incident happened. The Japanese Kwantung Army blew up a railway section and blamed a Chinese warlord. The Japanese army then began to conquer Manchuria.

Kenji Doihara, a Japanese spy, visited Puyi. He suggested Puyi become the leader of a new state in Manchuria. The Japanese also tried to scare Puyi into moving. They bribed a cafe worker to tell Puyi that someone wanted to harm him.

Puyi's wife, Empress Wanrong, was against him going to Manchuria. She called it treason. But Puyi decided to go. In November 1931, Puyi traveled to Manchuria to plan the new state of Manchukuo. He left his house in Tianjin by hiding in a car trunk. The Chinese government wanted to arrest him, but the Japanese protected him.

Puyi boarded a Japanese ship to Port Arthur. There, he was met by General Masahiko Amakasu, who became his minder. Puyi soon realized he was a prisoner. He was not allowed to leave the Yamato Hotel. Wanrong stayed in Tianjin at first. She was still against Puyi working with the Japanese. But she eventually joined him in Port Arthur.

A Puppet Emperor

In 1934, Puyi was made emperor of Manchukuo. His era name was "Kangde." This was his third time as emperor, but he was a puppet ruler for Japan. His life involved signing laws made by Japan. He also recited prayers and made formal visits. He mostly lived in the Salt Tax Palace. Puyi was very unhappy as a prisoner there. His moods changed often.

In May 1938, Puyi was declared a god by law. A special worship of the emperor began, similar to Japan's. Schoolchildren prayed to his portrait. Imperial documents and items became sacred. This happened because of the war between China and Japan. The Japanese wanted people to be more devoted to their emperor. They hoped making Puyi a god-emperor would have the same effect in Manchukuo. After 1938, Puyi was rarely allowed to leave the Salt Tax Palace.

When Japan lost World War II in 1945, Manchukuo also ended. Puyi fled and was captured by the Soviets. He was sent back to China in 1950.

Later Life and New Beginnings

The Soviets took Puyi to Siberia. He lived in a special hospital, then in Khabarovsk. He was treated well and kept some servants. He knew about the civil war in China from Soviet radio. The Soviet government refused to send Puyi back to the Republic of China. This likely saved his life. Puyi wrote to Joseph Stalin several times asking to stay in the Soviet Union. He even asked for a former palace to live in.

Life in Prison

When the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949, Puyi was sent back to China. He was important to Mao Zedong. Mao wanted to show that even the last emperor could change. This would show the power of the Chinese Communist Party. Puyi was to be "remodeled" to become a Communist.

In 1950, Puyi and other prisoners were sent to China. Puyi thought he would be executed. But he was surprised by the kindness of his Chinese guards. They told him this was a new life. Puyi spent ten years in the Fushun War Criminals Management Centre in Liaoning province. He was declared reformed. Puyi was often bullied by other prisoners. The warden, Jin Yuan, protected him. In 1951, Puyi learned his wife Wanrong had died in 1946.

Puyi had never brushed his teeth or tied his shoelaces. He had to learn these basic tasks in prison. This made other prisoners laugh at him. His "remodeling" included attending discussion groups about Marxism. Prisoners talked about their lives before prison. Puyi also saw places where the Japanese army had done terrible experiments. He felt shame and horror, noting: "All the atrocities had been carried out in my name."

A New Chapter

In late 1956, Puyi acted in a play. He enjoyed acting and continued to perform in plays about his life. During the Great Leap Forward, when many people faced hardship, Puyi's visits to the countryside were stopped. This was to protect his growing belief in communism.

Puyi came to Peking on December 9, 1959. He lived with his sister for six months. Then he moved to a government hotel. He got a job sweeping streets. On his first day, he got lost. He told people: "I'm Puyi, the last Emperor of the Qing dynasty. I'm staying with relatives and can't find my way home."

One of his first acts was to visit the Forbidden City as a tourist. He pointed out that many exhibits were things he used as a child. He supported the Communists and worked as a gardener. This job brought him happiness he never knew as emperor. Many people in the West were surprised Puyi was released after only nine years. Other leaders who acted like him were often executed.

In early 1960, Puyi met Premier Zhou Enlai. Zhou told him he was not responsible for becoming emperor as a child. But he was to blame for his actions later. Puyi said he wished he could apologize for his cruelty as a boy-emperor.

At 56, he married Li Shuxian, a nurse, on April 30, 1962. From 1964 until his death, he worked as an editor. His monthly salary was about 100 yuan.

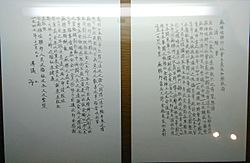

With encouragement from Chairman Mao Zedong, Puyi wrote his autobiography, From Emperor to Citizen. He wrote it with an editor named Li Wenda. The book took four years to write. Some parts of the book, especially about his prison life, are known to be overly positive.

Puyi often gave press conferences praising life in China. Foreign diplomats were curious to meet the "Last Emperor." Puyi was known for his kindness. Once, he accidentally knocked down an elderly lady with his bicycle. He visited her every day in the hospital with flowers until she was released.

Death and Legacy

In 1966, the Cultural Revolution began. The Red Guards saw Puyi as a symbol of old China. Puyi was protected by the police. His food, salary, and luxuries were taken away. But he was not publicly shamed like others. The Red Guards attacked his book because it was translated into other languages. Copies were burned.

Many of Puyi's family members had their homes raided. But Zhou Enlai used his power to protect Puyi and his family. Puyi's health got worse. He died in Peking on October 17, 1967, at age 61. He died from kidney cancer and heart disease.

Puyi's body was cremated. His ashes were first placed in a cemetery for important people. In 1995, his widow moved his ashes to a new cemetery. This cemetery is near the Western Qing Tombs, where four earlier Qing emperors are buried. In 2015, some of Puyi's family gave him and his wives special names after their death.

Portrayal in Movies and TV

Puyi's life has been shown in many films and television series:

- The Last Emperor, a 1986 Hong Kong film.

- The Last Emperor, a famous 1987 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. John Lone played the adult Puyi.

- Aisin-Gioro Puyi, a 2005 Chinese documentary film.

- The Founding of a Party, a 2011 Chinese film.

- 1911, a 2011 historical film.

- The Misadventure of Zoo, a 1981 Hong Kong TV series.

- Modai Huangdi (The Last Emperor), a 1988 Chinese TV series based on Puyi's autobiography.

- Feichang Gongmin (Unusual Citizen), a 2002 Chinese TV series.

- Ruten no Ōhi – Saigo no Kōtei, a 2003 Japanese TV series.

- Modai Huangfei (The Last Imperial Consort), a 2003 Chinese TV series.

- Modai Huangdi Chuanqi (The Legend of the Last Emperor), a 2015 TV series.

See Also

In Spanish: Puyi para niños

In Spanish: Puyi para niños

- Chinese emperors family tree (late)

- Dynasties in Chinese history

- List of heads of regimes who were later imprisoned

- List of monarchs who lost their thrones in the 20th century

- Puyi Wikimedia photos

Images for kids

-

Gobulo Wanrong, Puyi's wife and Empress of China

-

Puyi as emperor of Manchukuo.

-

Puyi and Wanrong leaving their hotel on 8 March 1932 before travelling to the official Manchukuo founding ceremony in Changchun