History of Cork facts for kids

Cork, located on Ireland's south coast, is a vibrant city and the second largest in the Republic of Ireland, after Dublin. It's also the biggest city in the province of Munster. Cork has a long and interesting history that goes all the way back to the sixth century!

Contents

How Cork Began

Cork started as a peaceful monastic settlement, founded by St Finbar in the 500s. But the city we know today really began between 915 and 922. That's when Viking settlers arrived and set up a busy trading community. These Vikings were skilled traders and sailors. Later, in the 1100s, new settlers called Anglo-Normans took over the Viking settlement. The Vikings of Cork even fought a big naval battle against the Normans in 1173, but they were defeated.

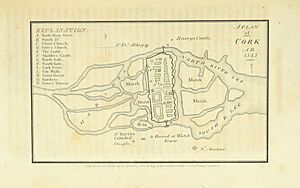

Cork received its official city charter from Prince John in 1185. This charter gave the city special rights and rules. Over many years, Cork was rebuilt many times because of fires. The city used to have strong walls all around it, and you can still see parts of these walls and old gates today. The leader of Cork was first called the Mayor in 1318, and then the title changed to Lord Mayor in 1900. Cork is sometimes called the 'rebel city' because of its history of standing up for itself!

A City Outpost

For a long time in the Middle Ages, Cork was like an English island in the middle of a mostly Irish countryside. It was far from the main English government in the Pale (around Dublin). Local Irish and Norman lords would demand "Black Rent" from the citizens. This was money paid to stop them from attacking the city.

Cork's government was run by about 12 to 15 rich merchant families. They made their money by trading with other countries in Europe. They would send out things like wool and animal hides, and bring in goods like salt, iron, and wine.

Around the 1300s, about 2,000 people lived in Cork. But in 1349, something terrible happened: the Black Death arrived. This sickness, known as bubonic plague, killed almost half the people in the town.

In 1491, Cork played a part in the English Wars of the Roses. A man named Perkin Warbeck pretended to be an English prince and came to Cork to get support. The former mayor of Cork and other important citizens joined him. But the rebellion failed, and they were all caught and executed. This event is another reason why Cork is known as the 'rebel city'.

Times of Conflict

The way Cork was changed a lot during the Tudor conquest of Ireland (around 1540–1603). For the first time, the English government took control of all of Ireland. Thousands of English settlers arrived, and they tried to make everyone follow the Protestant Reformation, even though most people were Catholic.

Cork suffered during these wars. During the Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–83), many people from the countryside ran to the city to escape the fighting. But they also brought another outbreak of the bubonic plague with them.

Shandon Castle, just outside the city walls, became an important English base. Cork generally supported the English Crown during these conflicts. However, the people of Cork wanted to be allowed to practice their Roman Catholic religion freely. In 1603, the citizens of Cork, along with other cities, rebelled. They kicked out Protestant ministers, arrested English officials, and demanded religious freedom. The English army quickly put an end to this revolt.

In 1641, a big rebellion broke out in Ireland. Cork became a safe place for English Protestants and stayed in their hands throughout the Irish Confederate Wars. In 1644, the commander of English forces in Cork, Murrough O'Brien, made Catholic townspeople leave the city. This was the start of Protestant control over the city, which lasted for nearly 200 years.

Later, in 1690, during the Williamite war in Ireland, Cork was attacked and captured by an English army led by John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough.

Cork in the 1700s

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, French Protestants called Huguenots came to Cork. They were escaping religious persecution in France. You can still see their influence in names like the Huguenot Quarter and French Church Street. Many new buildings were built in Cork during the 1700s. Like Dublin, much of Cork's old medieval style was replaced by grand Georgian buildings.

During the 1700s, trade in Cork's port grew a lot. Cork merchants sent huge amounts of butter and beef to Britain, France, and the Caribbean. This trade was very important for the city's economy.

Growth and Challenges

In the early 1800s, Cork's population grew rapidly, reaching about 80,000 by the mid-1800s. This increase was partly because people moved from the countryside to the city, trying to escape poverty. In the 1840s, a terrible event called the Great Irish Famine caused even more people to come to Cork. This led to extreme poverty and crowded conditions in the city.

Later in the 1800s, Cork's population actually went down a bit because many people emigrated. They left Ireland to go to places like Britain or North America. Cork and nearby Cobh became major departure points for Irish emigrants, especially after the Great Famine.

During the 1800s and early 1900s, important industries in Cork included brewing (making beer), distilling (making spirits), wool production, and shipbuilding. The city also saw improvements like gas street lights in 1825. Two local newspapers, the Cork Constitution and the Cork Examiner, started publishing. Very importantly, the railway reached Cork in 1849, which helped modern industry grow. Also in 1849, University College Cork opened its doors.

You can still see a lot of 19th-century architecture in Cork today. Many buildings from the Victorian period, like banks and department stores, are still standing.

War and Change

From the 1910s to the 1920s, Cork was a central place for Irish nationalism. Many people supported the idea of Irish Home Rule, which meant Ireland would govern itself while still being part of the British Empire.

After World War I began in 1914, many young men from Cork joined the British army. They fought in places like Gallipoli and on the Western Front, and many were sadly killed.

Between 1916 and 1923, Cork was caught up in a big conflict between Irish nationalists and the British government. This period eventually led to Ireland gaining its independence in 1922. However, it also led to a difficult civil war between different Irish groups.

In 1916, during the Easter Rising, about 1,000 Irish Volunteers in Cork prepared for a rebellion against British rule, but they didn't end up fighting. However, during the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), Cork saw a lot of violence.

The city suffered greatly from the actions of the Black and Tans. These were a special police force sent to fight the Irish Republican Army (IRA). On March 20, 1920, Thomas Mac Curtain, the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork, was shot and killed in his home. His successor, Terence McSwiney, was arrested in August 1920 and died on hunger strike in October.

On December 11, 1920, the city centre was destroyed by fires. These fires were started by the Black and Tans as revenge for IRA attacks. Over 300 buildings were burned, and two suspected IRA men were killed. Even after this terrible event, IRA activity continued in the city until a truce was agreed in July 1921.

The Civil War in Cork

After the War of Independence, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed, which created the Irish Free State. However, many local IRA units did not agree with this treaty. After British troops left in early 1922, these anti-Treaty forces took over military barracks in Cork.

By July 1922, when the Irish Civil War began, Cork was held by the anti-Treaty forces. They saw it as part of a "Munster Republic" that would keep the original Irish Republic alive.

However, Cork was captured in August 1922 by the pro-Treaty National Army. They landed near Passage West with troops and artillery. There was fighting for three days in the hills around Douglas and Rochestown. The anti-Treaty forces didn't make a strong stand in Cork itself. They burned some buildings and barracks they had been holding (like Elizabeth Fort and Collins Barracks) and then scattered.

After this, they switched to guerrilla warfare, destroying roads and bridges connecting Cork to the rest of the country. Michael Collins, the leader of the National Army, was killed in an ambush west of the city on August 22, 1922. The guerrilla fighting continued until April 1923, when the anti-Treaty side called a ceasefire.

Cork Today

Since Ireland gained independence, Cork has been known as the Republic of Ireland's second city. It has produced important political leaders, like Jack Lynch, who became Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) in the 1960s. People in Cork sometimes jokingly call it the "real capital."

From the 1920s onwards, the city cleared its inner-city slums. People who lived there were moved to new housing estates on the edge of the city, especially on the north side. Cork's economy faced challenges in the late 20th century as old factories closed down. The Ford car factory closed in 1984, and so did the Dunlop tyre factory. Shipbuilding in Cork also ended in the 1980s, leading to high unemployment.

However, in the 1990s, new industries came to Cork. For example, Marina Commercial Park was built where the old Ford and Dunlop plants used to be. Cork Airport Business Park opened in 1999. Cork, like other Irish cities, benefited from the "Celtic Tiger" economic boom. This brought growth in areas like information technology, medicines, brewing, distilling, and food processing. The Port of Cork is still a very busy and important port. In the 21st century, tourism has also grown, and in 2005, Cork was even named European Capital of Culture.

See also

- County Cork

- Greater Cork

- Metropolitan Cork

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |