History of Guernsey facts for kids

The history of Guernsey tells the story of this island, from its very first inhabitants to the modern society we see today. It's a journey through time, showing how people lived, worked, and defended their home.

Contents

Ancient Times: Prehistory and Romans

Around 8,000 years ago, the sea level rose, creating the English Channel. This separated the land that would become Guernsey and Jersey from mainland Europe. Soon after, early farmers from the Stone Age settled on Guernsey's coasts. They built amazing stone structures like dolmens (ancient tombs) and menhirs (tall standing stones). Guernsey has two unique carved menhirs, and one dolmen, L'Autel du Dehus, even has a carving known as Le Gardien du Tombeau (The Guardian of the Tomb).

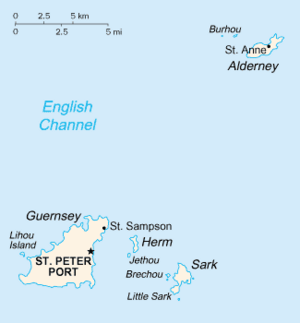

Later, during the time of the Roman Empire, people fled to places like the Channel Islands. Roman trade also came to Guernsey. A Roman shipwreck from the 3rd century was found in St Peter Port harbour. This shows that Guernsey was part of a busy trade route, with ships carrying silver, pottery, and wine. A Roman signal station fort from the 5th century was also found in Alderney.

Early Days: Christianity and Dukes

The Arrival of Christianity in Guernsey

As people moved to Brittany, they settled on islands like Guernsey. It's believed that Saint Sampson, a missionary from Wales, brought Christianity to Guernsey. He later became an abbot in Brittany.

A chapel dedicated to Saint Magloire, a nephew of Saint Samson, once stood in the Vale. Even though the chapel is gone, it suggests that Christian worship began in Guernsey before the year 600. Around 968 AD, monks from the famous Mont Saint-Michel monastery in Normandy came to Guernsey. They set up a religious community in the north of the island.

Guernsey and the Dukes of Normandy

The Bailiwick of Guernsey's history with Normandy began in 933. The islands came under the control of William Longsword, the son of the first Duke of Normandy. The Channel Islands are actually the last remaining parts of the old Duchy of Normandy. Even today, Queen Elizabeth II's traditional title as head of state in the islands is Duke of Normandy.

Legend says that in 1032, Robert I, Duke of Normandy (who was William the Conqueror's father) took shelter in Guernsey during a storm. He gave land, now called the Clos du Valle, to the monks. Later, in 1061, pirates attacked the island. Duke William sent Sampson D'Anneville, who, with the monks' help, drove the pirates away. As a reward, Sampson D'Anneville and the monks received half of the island.

When King John lost Normandy to France in 1204, the Channel Islands became separated from mainland Europe. This meant that whenever England and France fought, trade to and from Guernsey was often stopped. Even in peacetime, pirates and naval forces frequently attacked the island.

Because of these threats, fortifications were improved, and the Royal Guernsey Militia was formed. Every man on the island had to serve in this militia to defend Guernsey. During the Hundred Years' War, Guernsey was occupied by the French for two years, and Castle Cornet for seven. Attacks happened many times.

In 1348, the terrible Black Death arrived, causing many people to die. In 1372, mercenaries from Aragon, led by Owain Lawgoch, invaded the island. Islanders later remembered Lawgoch and his dark-haired fighters as an invasion by fairies from across the sea.

Guernsey's ships became better, and trade grew. In the 14th century, ships were small, carrying goods with crews of 8-20 men. During wars, ships could be captured as prizes, and even in peacetime, piracy was a problem.

The Reformation and Religious Changes

In the mid-1500s, Guernsey was influenced by Calvinism, a type of Protestantism, from Normandy. During a time when Protestants were persecuted, three local women, known as the Guernsey Martyrs, were burned at the stake in 1556 because of their Protestant beliefs. Two years later, Elizabeth I became queen, and Catholicism faded in Guernsey.

French attacks and piracy continued to be problems for Guernsey's trade in the 16th century. England needed the islands to be loyal, so Guernsey and Jersey were given special privileges. One important privilege was neutrality, which allowed them to trade with both France and England, even when these countries were at war. This trade brought in money from taxes, which helped pay for the island's defenses.

Modern History: Wars, Trade, and Growth

The English Civil War in Guernsey

During the English Civil War, Guernsey supported the Parliamentarians, while Jersey remained loyal to the King. Guernsey's choice was partly because many islanders were Calvinists. Also, King Charles I had not helped some Guernsey sailors captured by pirates. However, not everyone in Guernsey agreed; there were some Royalist uprisings. Castle Cornet was held by Royalist troops and was constantly attacked by the town of St Peter Port. It was one of the last Royalist strongholds to surrender in 1651.

Trade and Emigration in the 17th and 18th Centuries

The cod fishing trade with Newfoundland was important for Guernsey until about 1700. After that, smuggling became more profitable. Businesses were set up to buy goods for smugglers. When smuggling declined in the late 1700s, legal privateering took over as the most profitable business.

During wars against France and Spain in the 17th and 18th centuries, Guernsey shipowners could get special permits called Letters of Marque. These allowed their merchant ships to become licensed privateers, meaning they could attack and capture enemy ships. This was very profitable. In the first ten years of the 18th century, Guernsey privateers captured 608 enemy ships. To reduce risk, people would buy shares in a ship, becoming rich without ever sailing. Ships became larger and better armed. During the American Revolutionary War, Guernsey and Alderney privateers captured 221 ships, worth a huge amount of money today. Guernsey played a key role in blocking Britain's enemies.

In the late 17th century, Charles II of England gave an island to George Carteret, the Bailiff of Jersey. This island was renamed New Jersey. Channel Island trading ships also visited New England, leading many islanders to set up businesses and settle overseas. By the early 18th century, Guernsey residents were moving to North America. Guernsey County in Ohio was founded in 1810.

Regular trade continued, with fishing always being important. Knitting was a big home industry. Overseas ships carried goods like wood, sugar, rum, coal, tobacco, salt, and wine, trading mainly with Europe, the West Indies, and the Americas.

The 19th Century: Prosperity and Change

Privateering continued to bring profits during the Napoleonic Wars. London issued thousands of Letters of Marque, and Guernsey captains received hundreds of them. These permits specified which enemy ships could be captured by which Guernsey ship. Ships became stronger and better armed. New laws were introduced to fairly value the captured ships and goods.

Fort George was built between 1780 and 1812 to house more British troops, in case of a French invasion during the Napoleonic Wars. Le Braye du Valle was a tidal channel that separated the north of Guernsey, making it a tidal island. This channel was drained and reclaimed in 1806 for defense. The eastern end became the town and harbour of St Sampson's, now Guernsey's second-biggest port. New roads were also built for military use.

In 1821, Guernsey's population was over 20,000, with more than half living in St Peter Port. By 1901, the island's population had doubled.

The 19th century brought great wealth to Guernsey, thanks to its success in global sea trade and the growing stone industry. Ships traveled further for trade. A notable Guernseyman, William Le Lacheur, started the coffee trade between Costa Rica and Europe. Shipbuilding also grew between 1840 and 1870, but declined when iron ships became popular.

The quarrying industry was a major employer in the 19th century. Guernsey granite was highly valued, used for London Bridge and many London roads. This led to hundreds of quarries in the northern parishes. Horticulture also developed, with glasshouses first growing grapes, then tomatoes. This became a very important industry from the 1860s. Tourism also grew during the Victorian era, bringing money to the island. Famous writer Victor Hugo was one of the well-known people who found refuge in Guernsey.

Light industries often appeared and then moved on. For example, a Scottish firm, James Keiller, set up in Guernsey from 1857 to 1879 to avoid high sugar taxes in the UK. They made marmalade that was sold worldwide.

It was common for the island to deport people who were not considered "local," including those who were poor, criminals, or vagrants. Between 1842 and 1880, 10,000 people were deported. This included local-born widows and children of "foreign" men, and even people who had lived in Guernsey for over 50 years. This policy aimed to reduce the burden on parishes to care for the poor and discourage people from other countries from moving to Guernsey.

By the end of the century, changes were finally made. English began to be taught in schools and used in courts. There were also some reforms to voting and to the unfair treatment of non-locals, who could be deported or arrested for small debts, and who found it very hard to be recognized as "local," no matter how long they lived there.

The 20th Century: Wars and New Industries

Guernsey in World War I

During World War I, about 3,000 men from Guernsey served in the British army. Around 1,000 of them were in the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry regiment, formed in 1916. In 1917, Guernsey hosted a French flying boat squadron that helped fight German submarines. The Guernsey Roll of Honour lists 1,343 people from the Bailiwick who died or served in the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry.

The economic downturn of the 1930s also affected Guernsey. Unemployed workers were given jobs building sea defenses and new roads, like Le Val des Terres, which opened in 1935.

Guernsey in World War II

For most of World War II, German troops occupied Guernsey. Before the occupation, many Guernsey children were sent to England for safety. Some never saw their families again.

The German forces deported some islanders to camps in Germany. Among them was Ambrose Sherwill, who was the civilian leader of Guernsey during the occupation. Three islanders of Jewish background were sent to Auschwitz and never returned. In Alderney, four camps were built for forced laborers, mostly from Eastern Europe. Two of these were run by the SS, making them the only concentration camps on British soil.

The Germans also made new laws. For example, a reward was offered to anyone who reported people painting "V-for Victory" signs, which islanders used to show their loyalty to Britain.

Guernsey was heavily fortified by the Germans during World War II, much more than its strategic importance suggested. Hitler believed the Allies would try hard to recapture the islands. So, over 20% of the materials used for the "Atlantic Wall" (Germany's coastal defense) were sent to the Channel Islands. Many German fortifications are still visible today, some are even open to the public.

By late 1944, starvation threatened the island after German forces were cut off from supplies. The SS Vega, a ship chartered by the Red Cross, brought food parcels and other essential supplies to the island.

Guernsey was finally liberated on May 9, 1945.

Guernsey After the War

After 1945, islanders had to rebuild their lives. Evacuees returned, especially children who barely remembered their families. Many homes were damaged, and the island had a huge debt. Tourism was gone, and the growing industry was hurt. Rationing continued until the mid-1950s, just like in the UK.

Many traditional businesses like fishing and quarrying did not return. Islanders looked for new opportunities. Since physical import/export was difficult due to small harbors and high costs, they focused on controlling trade. For example, a Guernsey business controlled the supply of Mateus Rosé wine to the UK, and it became the world's top-selling wine.

By the 1960s, Guernsey had recovered. Tourism was important again, and the horticulture industry was booming, exporting 500 million tomatoes annually. Then came a crash. Cheap fuel in the North Sea allowed the Netherlands to heat their greenhouses cheaply, undercutting Guernsey's prices. This, combined with rising fuel costs, led to the complete end of Guernsey's tomato industry by the late 1970s. Rules were also introduced to make it harder and more expensive for people to move to the island, as there was a fear of too many people moving there.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Guernsey's finance industry began to boom. This was a big change for people who had worked in growing plants, moving to office jobs. Profits and salaries were good, and the island had money for long-term projects. This growth continued through the 1990s, with related industries like captive insurance and fund management keeping unemployment low. Tourism declined in the 1980s as holidays in Spain became much cheaper than Guernsey. Now, the island aims to attract higher-end tourists.

Light industries continued to appear and operate in Guernsey for a few decades, such as electronics company Tektronix (1957-1980s) and the current Specsavers, which started in 1984.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |