History of Martinique facts for kids

The island of Martinique has a long and interesting history. It was first settled by native peoples, then explored by Europeans, and later became an important French colony. Over the centuries, it faced many challenges, including natural disasters, conflicts, and the difficult period of slavery.

Contents

- Early Inhabitants and Volcanoes (100–1450)

- European Exploration (1450–1600)

- French Settlement and Growth (17th Century)

- Coffee, Wars, and Hurricanes (1700–1788)

- The French Revolution and Its Impact

- Napoleonic Era and Slavery (1800–1815)

- Towards Emancipation and Modernization (1815–1899)

- The 20th Century

- See also

- Images for kids

Early Inhabitants and Volcanoes (100–1450)

The first people to live on Martinique were the Arawaks. They arrived from South America around 130 AD. Around 295 AD, the volcano Mount Pelée erupted. This caused many people on the island to die. The Arawaks returned and settled the island again around 400 AD. Later, around 600 AD, the Island Caribs arrived. They took over from the Arawaks and lived on the island for many centuries.

European Exploration (1450–1600)

The famous explorer Christopher Columbus mapped the region in 1493. This made Europeans aware of the island. However, Columbus did not actually land on Martinique until June 15, 1502. This was during his fourth voyage. He left some pigs and goats on the island. But the Spanish were more interested in other parts of the New World, so they did not settle Martinique.

French Settlement and Growth (17th Century)

In 1635, a French company sent settlers to Martinique. Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc arrived on September 1, 1635. He came with about 80 to 100 French settlers from another island. They faced some resistance from the Caribs but quickly overcame it with their better weapons. The settlers built Fort Saint Pierre in the northwest. This area later became the town of St. Pierre. The first governor was Jean Dupont.

Developing the Colony

The next year, d'Esnambuc became ill and gave control to his nephew, Jacques Dyel du Parquet. The colony grew to about 700 men. They cleared land to grow food like manioc and potatoes. They also grew crops for export, such as tobacco, indigo, and later cocoa and cotton. French and foreign traders often visited to buy these goods. This helped Martinique become a successful colony. In 1638, another fort, Fort Saint Louis, was built. It was improved in 1640 with stone walls and cannons.

Conflicts and Control

Over the next 25 years, the French gained full control of the island. They fought the Caribs and pushed them back to the Caravelle Peninsula. Growing sugar was very profitable, even though it required a lot of work. Martinique soon focused on growing and trading sugar. In 1685, King Louis XIV created "Le Code Noir" (the Black Code). This set rules for bringing Africans to work as slaves on French sugar plantations. Slavery and slave revolts greatly influenced the island's economy and politics for over 200 years.

Early Economy and Administration

French settlers were often poor farmers looking for a better life. Many were indentured servants. They had to work for three years, hoping to get their own land afterward. However, the hard work and hot climate meant few survived their three years. So, new workers were always needed. Despite this, Martinique's economy grew under du Parquet. It exported goods to France and nearby English and Dutch colonies. In 1645, the Sovereign Council was set up. It had the power to grant noble titles. In 1650, du Parquet bought the island from the French company.

Sugar and Rum Production

In 1650, Father Jacques du Tetre built a still. This machine turned sugarcane waste into molasses, which became a major export. In 1654, du Parquet allowed 250 Dutch Jews to settle in Martinique. They had fled Brazil and became involved in the sugar trade. Sugar was highly sought after in Europe and became Martinique's biggest export.

French Crown Takes Over

After du Parquet's death, his widow governed for his children. In 1658, King Louis XIV took back control of the island. He paid the du Parquet children a large sum of money. At this time, Martinique had about 5,000 settlers and a few Carib Indians. The Caribs were eventually pushed out or exiled by 1660. From 1693 to 1705, Père Labat, a French priest, lived at the Fonds Saint-Jacques estate. He improved the distillery there. He was also an explorer, architect, and soldier.

More Conflicts and Development

In 1664, Louis XIV gave the island to a new company, the French West India Company. The next year, a Dutch fleet came to Martinique during a war with England. In 1666 and 1667, the English tried to attack but failed. The Treaty of Breda (1667) ended these fights. In 1672, Louis XIV ordered the building of a strong fort, Fort Saint Louis, at Fort Royal Bay. The next year, the company decided to build a town at Fort Royal, even though it was a swampy area. The French West India Company failed in 1674. Martinique then came under the direct rule of the French king.

Governors and Fortifications

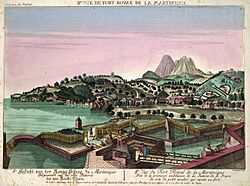

In 1675, the first Governor General of the West Indies, Jean-Charles de Baas-Castelmore, arrived. His successor, Charles de La Roche-Courbon, comte de Blénac, served several times. He planned the city of Fort Royal and improved Fort Saint Louis. De Blénac oversaw a 10-year project to build a large wall around the fort's peninsula. As the town grew, the swampy areas were cleared. By 1681, Fort-Royal was the administrative and military capital. However, Saint Pierre remained the main commercial center.

The Black Code and Jews

In 1685, King Louis XIV issued the "Code Noir" (Black Code) in France. This set of 60 laws regulated slavery in the colonies. It allowed some cruel acts but also tried to forbid others. It treated slaves as property. The code also ordered all Jews to leave the French islands. Many of them moved to the Dutch island of Curaçao and became successful there. In 1692, Fort Royal was officially named the capital of Martinique. In 1693, the English tried to attack Martinique again but were unsuccessful.

Coffee, Wars, and Hurricanes (1700–1788)

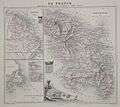

In 1720, a French naval officer named Gabriel de Clieu brought a coffee plant seedling from Paris to Martinique. He planted it on the slopes of Mount Pelée. By 1726, he had his first coffee harvest. By 1736, the number of slaves in Martinique had grown to 60,000 people. In 1750, Saint Pierre had about 15,000 residents, while Fort Royal had only about 4,000.

British Occupation and Treaties

During the Seven Years' War, the British captured Martinique in early 1762. After Britain won the war, there was a chance they would keep the island. However, Martinique's sugar trade was so valuable to France. So, in the Treaty of Paris (1763), France chose to get Martinique and Guadeloupe back instead of Canada. During the British occupation, Empress Joséphine, who would later marry Napoleon, was born on Les Trois-Îlets. In 1762, a yellow fever outbreak occurred. In 1763, France set up separate governments for Martinique and Guadeloupe.

Natural Disasters and Important Births

On August 2, 1766, Louis Delgrès was born. He was a free black man of mixed race. He later fought for France and led a resistance against the return of slavery in Guadeloupe. On August 13, 1766 or 1767, a hurricane and earthquake hit the island. Between 600 and 1600 people died. At that time, Martinique had about 450 sugar mills, and molasses was a major export. By 1774, when white indentured servitude ended, there were about 18 to 19 million coffee trees on the island.

In 1779, the future Empress Joséphine sailed to France to meet her husband. The next year, the Great Hurricane of 1780 struck Martinique. It was one of the worst hurricanes in history, killing 9,000 people. In 1782, a French admiral sailed from Martinique to attack Jamaica. However, the French suffered a major defeat in the battle of the Saintes against the British navy.

The French Revolution and Its Impact

The French Revolution (1789) also affected Martinique. Some planters and their slaves moved to Trinidad to grow sugar and cocoa. A French official from Martinique, Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry, opposed giving voting rights to free people of color. On April 4, 1792, the French government gave citizenship to all men of color. An official was sent to Martinique to apply this law. However, the local assembly refused to let him land with his troops. In 1793, there was a small slave rebellion in Saint Pierre, but it failed. Six leaders were executed. On February 4, 1793, a local leader signed an agreement with Britain. This put Martinique under British rule to prevent the French Revolution's ideas from spreading there. The agreement also guaranteed that French colonists could keep their slaves.

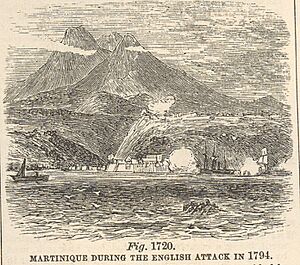

In 1794, the French government officially abolished slavery. But before this news reached Martinique, the British invaded and occupied the island. British forces captured Fort Royal and Fort Saint Louis on March 22. They took Fort Desaix two days later. On March 30, 1794, the British occupation brought back the old French system, including slavery. They also banned all gatherings of black people and slave meetings, as well as Carnival.

Napoleonic Era and Slavery (1800–1815)

In 1800, Jean Kina, a former slave, led a rebellion in support of free black people's rights. British troops quickly stopped it. Kina was sent to England. In 1802, the British returned Martinique to France under the Treaty of Amiens. Napoleon Bonaparte officially brought back slavery in the French colonies. However, in Martinique, slavery had never truly ended due to the British occupation. In 1796, Napoleon married Joséphine de Beauharnais, who was from Martinique. In 1804, she became Empress of France.

Conflicts and Abolition of Slave Trade

During the Napoleonic Wars, the British set up a fort at Diamond Rock in 1804. From there, they bothered ships entering the port for 17 months. The French eventually sent a large fleet and recaptured the island after heavy fighting. The British captured Martinique again in 1809 and held it until 1814. In 1813, a hurricane killed 3,000 people in Martinique. During Napoleon's brief return to power in 1815, he abolished the slave trade. The British also briefly re-occupied Martinique. The British, who had ended their own slave trade in 1807, pushed Napoleon's successor, Louis XVIII, to keep the ban. It became truly effective in 1831.

Towards Emancipation and Modernization (1815–1899)

In 1822, a slave uprising resulted in some deaths and injuries. Many slaves were severely punished. Martinique also suffered from earthquakes. In 1839, a strong earthquake killed 400 to 700 people. It badly damaged Saint Pierre and almost destroyed Fort Royal. Fort Royal was rebuilt using wood to reduce earthquake risk. But this increased the risk of fire. That same year, Martinique had 495 sugar producers, making about 25,900 tons of sugar.

Abolition of Slavery

In February 1848, François Perrinon became head of the Committee of Colonists of Martinique. He was part of the group working to abolish slavery. On April 27, Victor Schœlcher got a decree passed to abolish slavery in the French Empire. Perrinon arrived in Martinique on June 3. However, the governor, Claude Rostoland, had already abolished slavery two days earlier. A slave's imprisonment had led to a revolt on May 20. Under pressure, Rostoland ended slavery to stop the uprising. That same year, Fort Royal was renamed Fort-de-France. In 1981, May 22 was made a national holiday to celebrate emancipation.

New Laborers and City Changes

In 1851, a law allowed the creation of two colonial banks, including the Bank of Martinique. In 1853, indentured laborers from India began arriving in Martinique. Plantation owners hired them to replace the freed slaves, who had left the plantations. This led to the creation of a small but lasting Indian community. Later, about 1,000 Chinese laborers also came. In 1857-58, the city government cleaned up and filled a flood channel in Fort-de-France. This channel had become a health hazard. In 1863, the Crédit Foncier Colonial opened in Saint Pierre. It provided long-term loans for building or updating sugar factories. In 1868, port improvements were finished at Fort-de-France. This helped the city compete with Saint Pierre in trade.

Rebellion and Economic Shifts

In 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, racial tensions led to a short rebellion in southern Martinique. A Martiniquan Republic was declared in Fort-de-France. Many rebels were tried, and 12 leaders were shot. Others were sent to French Guiana or New Caledonia. By this time, sugar cane covered about 57% of Martinique's farmland. But falling sugar prices forced many small sugar businesses to combine. Producers started making rum to try and improve their finances. When France established the French Third Republic in 1871, Martinique gained representation in the National Assembly.

Art and Literature

In 1887, the artist Paul Gauguin spent several months in a cabin near Saint Pierre. He created several paintings featuring Martinique during this time. There is now a small Gauguin museum in Le Carbet. That same year, the author Lafcadio Hearn visited Martinique and stayed for about two years. He later published books about his life there and a slave's story. By 1888, Martinique's population had grown to 176,000 people.

More Disasters and Public Buildings

Natural disasters continued to affect the island. A fire devastated much of Fort-de-France in 1890. The next year, a hurricane killed about 400 people. In the 1880s, architect Pierre-Henri Picq built the Schœlcher Library. It was a metal and glass building shown at the 1889 Paris Exposition. After the Exposition, the building was shipped to Fort-de-France and rebuilt there by 1893. The library first held 10,000 books donated by Victor Schœlcher, who fought for slavery abolition. Today, it has over 250,000 books. In 1895, Picq also built the Saint-Louis Cathedral in Fort-de-France.

The 20th Century

The end of slavery did not stop all labor problems. In 1900, a strike at a sugar factory led to police shooting and killing 10 workers.

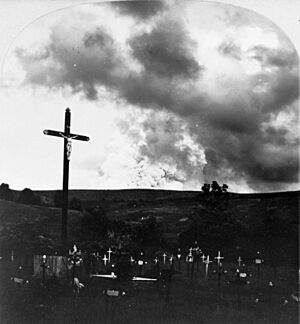

Mount Pelée Eruption (1902)

On May 8, 1902, the Mont Pelée volcano erupted. It destroyed the town of St. Pierre, killing almost all 29,000 people. Only two people survived: a shoemaker and a prisoner in a jail dungeon. Saint Pierre was the commercial capital, so four banks were destroyed. The town had to be completely rebuilt. Fort-de-France then became the new commercial capital. Many refugees from Martinique went to Dominica.

Recovery and World War I

A hurricane in 1903 killed 31 people and damaged sugar crops. A strong earthquake in 1906 caused more damage but no deaths. Over 5,000 Martiniquans left to work on the Panama Canal project. Saint Pierre was reestablished as a town in 1923. In 1908, the mayor of Fort-de-France was killed. Before World War I, France made military service compulsory in its colonies. Martinique sent 1,100 men each year for training. During World War I, 18,000 Martiniquans served, and 1,306 died. The French government used Martinique's rum production for the army. Production doubled as sugar mills became distilleries, helping the local economy recover.

Between the World Wars

After the world sugar market collapsed in 1921–22, farmers looked for a new crop. They introduced bananas in 1928. Mont Pelée became active again in 1929, causing Saint Pierre to be temporarily evacuated.

World War II (1939-1945)

Until mid-1943, Martinique officially supported the Vichy French government, which cooperated with Germany. The US and Britain tried to limit this. The US even planned to invade the island at one point. In June 1940, a French cruiser arrived in Martinique with 286 tons of gold from the Bank of France. This gold was stored safely at Fort Desaix. The island was blockaded by the British navy. The gold was used as a guarantee for supplies from the US. In mid-1943, the French admiral in charge returned to France. Supporters of the Free French (who fought against Germany) took control of the gold and the French fleet. In 1944, the American film To Have and Have Not was made. It was based on a novel by Ernest Hemingway. The movie is about an American boat captain who helps the Free French side in Vichy-controlled Fort-de-France.

Post-War Politics and Departmental Status

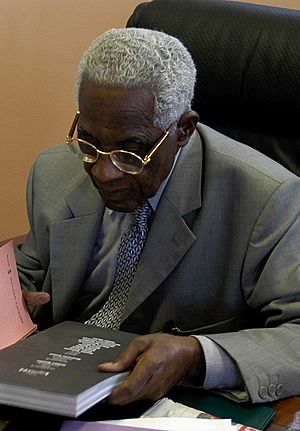

In 1945, Aimé Césaire was elected Mayor of Fort-de-France and a Deputy to the French National Assembly. He remained mayor for 56 years. Césaire later left the Communist Party after the Soviet Union suppressed the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. As a member of the Assembly, he helped create the 1946 law that changed former colonies into departments of France. In 1947, Admiral Robert, who had been in charge during the war, faced charges for his actions. He was sentenced but later pardoned.

Departmental Era (1946-Present)

In 1946, the French National Assembly voted to make Martinique a department of France. This meant it would be legally similar to any department in mainland France. However, some differences remained, especially in social security and unemployment benefits. Some believe that French funding has helped make up for the difficulties caused by slavery and relying only on sugar crops. Martinique has one of the highest living standards in the Caribbean. But it still depends on French aid. Everything in Martinique costs more than in France, while salaries are lower. This causes some inequalities and political issues.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Martinica para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Martinica para niños

Images for kids