History of Poland (1795–1918) facts for kids

From 1795 to 1918, Poland was not an independent country. It was divided and ruled by three powerful neighbors: Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy (later Austria-Hungary), and Russia. In 1795, the last of these divisions, called the partitions of Poland, ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Even without its own country, Poles never gave up hope for independence. Poland's location in Europe, between expanding empires like Prussia and Russia, meant its future was always tied to bigger European events.

Contents

The Napoleonic Period: A Spark of Hope

At the start of the 1800s, big changes were happening in Europe. Napoleon Bonaparte created a new French Empire in 1804. His wars with other European powers, especially those that had divided Poland, gave Poles a chance. Many Polish volunteers joined Napoleon's armies. They hoped that if Napoleon won, he would help Poland become independent again.

Napoleon didn't fully deliver on his promises. But in 1807, he created the Duchy of Warsaw from land that Prussia had taken from Poland. This duchy was mostly controlled by France, but it had some self-government. Many Poles believed that more of Napoleon's victories would lead to a fully restored Poland.

In 1809, under Jozef Poniatowski, the duchy took back some lands from Austria. However, the Russian Army occupied the duchy in 1813 while chasing Napoleon out of Russia. Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo in 1815 ended these Polish hopes. At the Congress of Vienna peace talks, the victorious powers removed the Duchy of Warsaw. They mostly confirmed the old divisions of Poland.

Even though it was short, the Napoleonic period was very important for Poland. It helped create a strong sense of Polish patriotism. It showed that Poland could rise again, even after being divided. A famous slogan from this time was "for your freedom and ours". This period proved that Poland's story wasn't over. Many people started to believe that Poland could become free again under the right conditions.

Nationalism and Romanticism: Fueling Polish Spirit

The early 1800s saw new ideas that boosted Polish calls for self-rule. Nationalism grew strong across Europe. It taught that each nation had its own value and culture. This idea helped Poles feel a stronger connection to their shared heritage.

Romanticism was an artistic movement that greatly influenced Polish national feelings. It celebrated folk cultures and often went against the old, conservative ways of thinking after Napoleon's defeat. Polish literature thrived during this time. Poets like Adam Mickiewicz wrote about patriotic themes and Poland's glorious past. Frédéric Chopin, a famous composer, also used his nation's tragic history as inspiration for his music.

These ideas first inspired educated Poles and some nobles. Over time, they spread to the common people. This helped create a broader idea of what it meant to be Polish, moving beyond just the noble class.

The Era of National Uprisings

For many years, the main goal of the Polish national movement was to regain independence right away. This led to a series of armed rebellions. Most of these happened in the Russian part of Poland. After the Congress of Vienna, Russia had created Congress Poland. It had a liberal constitution, its own army, and some self-rule. But in the 1820s, Russian rule became stricter. Secret groups formed to plan a revolt.

In November 1830, Polish troops in Warsaw rebelled. This started a new Polish-Russian war. The rebels asked France for help, but none came. They also didn't end serfdom, which meant they lost support from the peasants. By September 1831, Russia crushed the rebellion. Many fighters went into exile. Congress Poland lost its constitution and army, and Russia began harsh rule.

After this revolt, secret activities continued. Polish leaders in exile, especially in Paris, kept working for independence. Some, like Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, hoped for foreign support. Others wanted Poles to free themselves and linked independence with republicanism and freeing the serfs. But internal divisions and harsh surveillance made things hard.

A major setback came in 1846 with a revolt in Austrian Poland. This uprising failed badly when peasants turned against the noble leaders. This left Polish nationalists weak when revolutions swept across Europe in 1848.

The last big uprising happened in the Russian part in January 1863 (the January Uprising). After Russia's defeat in the Crimean War, Tsar Alexander II made some reforms, including freeing the serfs. But land reforms in Poland angered both nobles and young radical thinkers. Like in 1830, this revolt didn't get foreign help. Even though it had some progressive ideas, it couldn't get peasants to join. Russia crushed the rebellion by August 1864. Russia then completely removed Congress Poland's special status. The region became part of the Russian Empire and was ruled very strictly. When Russia freed the Polish serfs in early 1864, it removed a key reason for future Polish revolts.

"Organic Work": A New Approach

After the failed uprisings, Polish leaders realized that immediate independence was not possible. In the decades after the January Uprising, Poles changed their approach. They focused on strengthening the nation through education, economic growth, and modernization. This was called "Organic Work" (Praca organiczna). It meant building Polish society from the ground up.

This new method was well-suited to the times. International powers did not support Polish independence. Both Russia and Germany wanted to erase Polish national identity. The German Empire, formed in 1871, tried to make Poles in its eastern areas more German. Russia tried to make Poles more Russian. Both countries limited the use of the Polish language and culture. They also attacked the Roman Catholic Church. Germany had its "Cultural Struggle" (Kulturkampf), and Russia tried to spread its Orthodox Church.

Poles under Austrian rule (in Austria-Hungary after 1867) had an easier time. Austria was mostly Catholic, so Poles faced no religious persecution. Vienna also saw Polish nobles as allies. In return for loyalty, Austrian Poland, or Galicia, got a lot of self-rule in its administration and culture. Galicia became known as a place of tolerance compared to German and Russian Poland. Its local parliament had much power. The universities in Kraków and Lviv became centers of Polish thought and art. Many people from southern Poland still remember the Habsburg Empire fondly.

Social and Political Changes

Big social and economic changes happened in Poland in the late 1800s. Mining and manufacturing grew, especially in Russian and German Poland. This led to more cities and less importance for the old land-owning nobles. Many peasants left their farms. Millions of Poles moved to North America or to cities to find factory jobs. These changes created new social tensions. City workers faced hard conditions.

These changes also transformed politics. New parties and movements appeared. Workers' problems led to peasant and socialist parties. Józef Piłsudski led a moderate socialist group that strongly supported Polish independence. By 1905, his Polish Socialist Party was the largest socialist party in the Russian Empire. On the right, Roman Dmowski's National Democracy combined nationalism with hostility toward minorities. By the early 1900s, Polish political life became more active again. Piłsudski and Dmowski became key figures in Polish affairs. After 1900, only in the Prussian sector was political activity suppressed.

First World War: The Road to Freedom

When World War I began, Poland was caught between Germany and Russia. This meant terrible fighting and huge losses for Poles from 1914 to 1918. The war divided the three empires that ruled Poland. Russia fought against Germany and Austria-Hungary. This gave Poles a chance to gain power. Both sides offered promises of freedom if Poles would support them. Austria wanted to add Congress Poland to its territory. So, it allowed Polish nationalist groups to form. Russia recognized Poland's right to self-rule and allowed a Polish National Committee to support its side. In 1916, Germany and Austria declared a new Regency Kingdom of Poland (1916–1918) to gain Polish support and soldiers. This new kingdom was small, but it had its own government and army.

As the war continued, the idea of Polish self-rule became more urgent. Roman Dmowski worked in Western Europe, trying to convince the Allies to unite Polish lands under Russian rule first. Meanwhile, Józef Piłsudski correctly believed that the war would destroy all three ruling empires. He formed the Polish Legions to help the Central Powers defeat Russia. This was his first step toward full Polish independence.

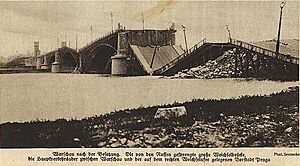

Much of the fighting on the Eastern Front happened in Poland. In 1914, Russian forces came close to Kraków. In 1915, the retreating Russian army looted and abandoned Polish areas. They also forced hundreds of thousands of people to leave. By the end of 1915, Germans occupied all of the Russian sector, including Warsaw. In 1916, another Russian attack in Galicia made life even harder for civilians. About 1 million Polish refugees fled eastward.

About 2 million Polish soldiers fought in the armies of the three ruling powers, and 450,000 died. Hundreds of thousands of Polish civilians were sent to labor camps in Germany. The war left many areas unlivable.

Poland Regains Independence

In 1917, two big events changed the war and led to Poland's rebirth. The United States joined the Allies. Also, a revolution in Russia weakened it and then removed Russia from the Eastern Front. The Bolsheviks took power and pulled Russia out of the war. At the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Bolsheviks gave up Russia's claims to Poland. After Germany's defeat in late 1918 and the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy, the path to an independent Poland was clear.

With Russia and Germany out of Poland, the calls for Polish freedom grew louder. Woodrow Wilson, the US President, made the rebirth of Poland one of his main goals for the war.

Józef Piłsudski became a hero after being jailed by Berlin for not obeying orders. The Allies broke the Central Powers' resistance by autumn 1918. The Habsburg monarchy fell apart, and the German government collapsed. In October 1918, Polish authorities took control of Galicia. In November 1918, Piłsudski was freed and returned to Warsaw. On November 11, 1918, the leaders of the Kingdom of Poland gave him all power. Piłsudski became the temporary Chief of State. Soon, all local governments pledged loyalty to Warsaw. Independent Poland, after 123 years, was reborn!

The new state first included former Congress Poland, western Galicia, and part of Cieszyn Silesia.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Polonia (1795-1918) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Polonia (1795-1918) para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |