History of Stockholm facts for kids

The history of Stockholm, the capital city of Sweden, has for many centuries been closely linked to the growth of what is now called Gamla stan, the Old Town. Stockholm's main purpose was always to be the Swedish capital and the biggest city in the country.

Contents

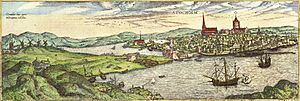

How Stockholm Began

The name 'Stockholm' can be split into two parts: "Stock" and "holm," which means "Log-islet." No one knows for sure how the name came about, so there are many old stories. One story from the 1600s says that people from the Viking village of Birka wanted to find a new home. They let a log tied with gold float in Lake Mälaren to decide the spot.

The log landed on what is now Riddarholmen. Today, the Tower of Birger Jarl stands there. People often mistakenly call it the oldest building in Stockholm. A more likely idea for the name comes from logs driven into the water north of the Old Town. Tests show these logs are from around the year 1000.

While there's no strong proof, it's believed that the Three Crown Castle, which was before the current Stockholm Palace, grew from these wooden structures. The medieval city likely expanded around it in the mid-1200s. Stockholm can be seen as the capital of the Lake Mälaren Region. Its roots go back to older cities like Birka (around 790–975) and Sigtuna (around 1000–1240). The capital simply moved several times.

Stockholm in the Middle Ages

The name Stockholm first appears in old writings in 1252. These letters were written by Birger Jarl and King Valdemar. However, they don't say much about what the city looked like or what happened there in the years after. Medieval Stockholm didn't have a neat, planned layout, which suggests it grew naturally. We do know that German merchants, invited by Birger Jarl, played a big part in founding the city.

By the end of the 1200s, Stockholm quickly became the largest city in Sweden. It also became the main political center and where the king lived. So, from its start, Stockholm has been Sweden's most important city. It was always connected to and depended on the Swedish government. However, even in the 1500s, during the reigns of Kings Eric XIV and John III, the city wasn't yet a national capital in the way we think of it today. The government often traveled with the kings.

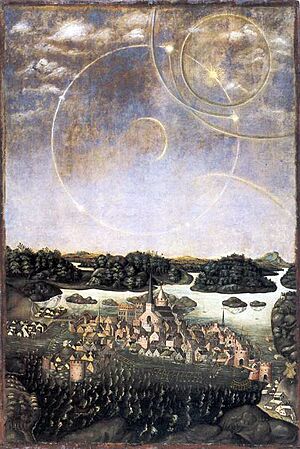

During the Kalmar Union (1397–1523), controlling Stockholm was key to ruling the kingdom. Because of this, different Swedish and Danish groups often attacked the city. In 1471, Sten Sture the Elder beat Christian I of Denmark at the Battle of Brunkeberg. But he lost the city to Hans of Denmark in 1497. Sten Sture took power again in 1501, leading to a Danish blockade from 1502–1509.

Hans' son Christian II of Denmark finally took Stockholm in 1520. He had many important nobles and citizens of Stockholm killed. This event is known as the Stockholm Bloodbath. When King Gustav Vasa finally took the city three years later, it marked the end of the Kalmar Union and the Swedish Middle Ages. He noticed that half the buildings in the city were empty.

By the end of the 1400s, Stockholm had about 5,000 to 7,000 people. This made it a small town compared to other European cities at the time. However, it was much larger than any other city in Sweden. Many people living there were Germans and Finns. The Germans were often the political and economic leaders in the city.

In the Middle Ages, German merchants handled most of the trade. They lived near the squares Kornhamnstorg ("Grain Harbour Square") and Järntorget ("Iron Square") in the city's southern part. Farmers from the countryside brought food and raw materials to the city. City craftsmen made goods. Most craftsmen lived near the main square Stortorget or on the oldest two streets, Köpmangatan ("Merchant Street") and Skomakargatan ("Shoemaker Street"). Other groups lived along the eastern or western main roads, Västerlånggatan and Österlånggatan.

Early Vasa Era

After Gustav Vasa took Stockholm, he gave back the city's special rights, which helped the citizens. The king kept control by overseeing the elections of city officials. By the mid-1500s, more officials were added to manage the city better and control state trade. Stockholm lost much of its freedom from the Middle Ages. It became tied to the state politically and financially. During the rule of Gustav Vasa's sons (1561–1611), the city council was always watched by a royal representative. Both magistrates and aldermen were chosen by the king.

Gustav Vasa invited Olaus Petri (1493–1552) to be Stockholm's city secretary. Together, they quickly brought in the new ideas of the Protestant Reformation. Church services began to be held in Swedish in 1525, and Latin was stopped in 1530. This led to a need for separate churches for the many German and Finnish-speaking people. In the 1530s, the German and Finnish parishes were created, and they still exist today. The king, however, did not like older chapels and churches. He ordered churches and monasteries on the hills around the city to be torn down, along with many charity places.

Stockholm had a city wall, so it didn't have to pay the same taxes as other Swedish cities. During Gustav Vasa's rule, the city's defenses were made stronger. In the Stockholm Archipelago, Vaxholm was built to guard the entrance from the Baltic Sea. The medieval layout of Stockholm stayed mostly the same in the 1500s. But the city's social and economic importance grew so much that no king could let it decide its own future. The most important export was bar iron, and most of it went to Lübeck.

During the rule of Vasa's sons, trade caused many Swedes to move to the city. But the trade and the money needed to control it were mostly in the hands of the king and German merchants from Lübeck and Danzig. During this time, Sweden didn't have the kind of government and offices that a modern capital needs. But Stockholm was the kingdom's strongest fort and the king's main home. King Eric XIV wanted to be like other European princes. He had the largest royal court his money could support. The royal castle was the biggest employer in the city.

Around 1560–80, most of the 8,000 citizens still lived on Stadsholmen. This central island was very crowded. The city began to spread onto the hills around it. Stockholm had no private palaces at this time. The only large buildings were the castle, the church, and the old Greyfriars monastery on Riddarholmen. The surrounding hills had no timber-framed buildings. They were mostly used for activities that needed a lot of space, smelled bad, or could cause fires. Even though some citizens had second homes outside the city, the people living on the hills were mostly poor. This included the royal staff living north of the city.

Great Power Era

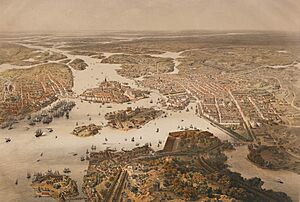

After the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), Sweden decided it would never again be embarrassed. After the death of Gustavus II Adolphus (1594–1632), Stockholm still looked like a medieval town. This made people hesitate to invite foreign leaders, fearing it would make Sweden look weak. So, Stockholm saw many big city plans during this time. The plans for the hills around the Old Town are still visible today.

Following the idea of mercantilism, trade and industry were focused in cities where they could be controlled more easily. Stockholm was very important for this. In 1636, Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna (1583–1654) wrote that making Stockholm a great capital was necessary for Sweden's power. He believed it would help all other cities grow. More government control over cities was not unique to Sweden, but it was probably stronger in Stockholm than anywhere else in Europe. To achieve this, the city's government was changed. Volunteer officials were slowly replaced by trained professionals.

City Growth and Plans

A big fire in 1625 helped start the reshaping of Stockholm. It destroyed the southwestern part of today's Old Town. Because of this, two new wide streets were built: Stora Nygatan and Lilla Nygatan. Along the eastern waterfront, the medieval wall was replaced by grand palaces, known as Skeppsbron.

For the hills surrounding the city – Norrmalm, Östermalm, Kungsholmen, and Södermalm – new city plans were made. These plans aimed to create wide, straight main streets. This project was carried out so thoroughly that in some parts of the city, no signs of the old medieval buildings remain. Many of the streets from this time still exist today. Some proposed streets were built later with small changes.

The population grew from less than 10,000 people in the early 1600s to over 50,000 by the mid-1670s. The city's income also increased a lot. In 1642, about 60% of that money was spent on construction projects.

Trade and Economy

Other Swedish cities lost their right to export goods due to the "Bothnian Trade Coercion." Most Swedish cities had a trade monopoly over a small area around them. But for Stockholm, most of the lands around the Gulf of Bothnia were part of its trade area. However, the state-given monopoly wasn't the only thing that helped Stockholm. It had one of the best natural harbors of that time. Throughout the 1600s, many foreign visitors were amazed to see large ships with "60 or 70 cannons" docked along the eastern quay next to the royal castle.

Unlike other Swedish cities, which could support themselves, Stockholm relied completely on goods passing through it. For example, it had about the same number of farm animals as Uppsala, which had only ten percent of Stockholm's population. All goods brought into Stockholm had to pass through one of six customs stations. About three-fourths of these goods were then exported from the city. Half of the remaining goods, mostly fish, came from the Baltic Sea. Corn came from the Lake Mälaren region. However, in the second half of the century, the fast-growing capital couldn't be supported by the Lake Mälaren region alone. So, it started to depend on imported corn from other areas.

Sweden had not been very active in international trade in the 1500s. German merchants and ships handled the export of Swedish goods like osmond iron, raw copper, and butter. This export was mainly seen as a way to get goods not available in Sweden, such as salt, wine, and luxury items for the royal court. With the idea of mercantilism around 1620, trade became a key source of government income. The Swedish economy then focused on exporting refined products, not just raw materials. Stockholm's share of the national economy stayed around two-thirds from 1590 to 1685. But in the first half of the 1600s, exports grew four times and imports five times. Most goods went to the Netherlands in the mid-1600s and to the UK in the early 1700s.

In the 1600s, the textile industry grew. The Paulinska manufakturerna (active 1673–1776) and the Barnängens manufaktur (active 1691–1826) textile factories were built. These became two of the biggest employers in Stockholm throughout the 1700s.

Age of Liberty (1718–1772)

| Population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Late 1600s | 55–66,000 | |

| Around 1720 | 45,000 | |

| Mid 1700s | 60,000 | |

| Mid 1800s | 90,000 | |

| Social Groups 1769–1850 (percent) |

||

| Group | 1769 | 1850 |

| Upper | 13 | 7 |

| Middle | 40 | 12 |

| Lower | 47 | 81 |

After the Greater Wrath and the Treaty of Nystad in 1722, Sweden was no longer a major European power. The next decades brought more problems. The Black death and the suffering from the Great Northern Wars made Stockholm the capital of a shrinking nation. This sadness grew even deeper when Sweden lost Finland in 1809. Even though Sweden partly recovered with the union with Norway in 1814, Stockholm was a struggling city from 1750 to 1850. It had fewer people and lots of unemployment. The city suffered from illness, poverty, and high death rates.

The Mälaren region became less important, while southwestern Sweden gained influence. As the population and wealth in the capital decreased, social classes became more equal. Wars led to more women than men during this time. In 1850, there were six widows for every widower. Stockholm had few children because many people were unmarried and infant deaths were high. The average lifespan was only 44 years. However, those who survived childhood often lived as long as people do today, unless they had very hard jobs.

People during this time could be divided into three social groups:

- Important people and officers.

- Craftsmen, small business owners, and officials.

- Workers, soldiers, servants, poor people, and prisoners.

Women's social standing was linked to their husband's. However, as craftsmen lost status with the start of industrialism, the working class grew. There was also a difference in wealth in the city. The current Old Town and lower Norrmalm were the richest areas. The suburbs (now part of central Stockholm) were poor.

In the 1700s, the Mercantile system from the previous century was further developed. This meant that local production was encouraged with loans and rewards. Imports were limited to raw materials not found in Sweden, through taxes. This era saw the rise of the "Skeppsbro Nobility." These were rich traders at Skeppsbron who made a lot of money by selling bar iron to other countries and by controlling chartered companies. The most successful was the Swedish East India Company (1731–1813). Its main office was in Gothenburg, but it was very important to Stockholm. This was because of the shipbuilding yards, trade houses, and the exotic goods the company brought in. Also, before these ships left Stockholm, about 100–150 men were hired for each ship, mostly from the city. A single trip to China could take 1–2 years, so the company had a huge impact on Stockholm.

During the 1700s, several big fires destroyed whole neighborhoods. This led to new building codes. These codes improved fire safety by banning wooden buildings. They also made the city more beautiful by following the 17th-century city plans. In the Old Town, the new royal palace was slowly finished. The outside of the Storkyrkan church was changed to match it. The skilled artists and craftsmen who worked for the royal court were very talented. They greatly improved the artistic quality in the capital.

Gustavian Era (1772–1809)

During the rule of Gustav III, Stockholm remained Sweden's political center and grew culturally. The king was very interested in the city's development. He created the Gustav Adolf square. The Royal Opera opened there in 1782. This matched the original plans by Tessin the Younger for a grand square north of the palace. The front of Arvfurstens palats on the opposite side looks just like the opera's old front.

The Norrbro bridge, designed by Erik Palmstedt (1741–1807), was a very ambitious project. It took ten years to finish. This bridge caused the city center to slowly move away from the medieval part.

The lively and often funny descriptions of Stockholm by singer and composer Carl Michael Bellman are still popular today.

This period ended when King Gustav IV Adolf was removed from power in 1809. Sweden lost Finland that same year. This meant Stockholm was no longer the geographical center of the Swedish kingdom.

Early Industrial Era (1809–1850)

For Stockholm, the early 1800s meant that only military projects were built on a large scale. These projects favored a more formal, classical style. In Sweden, this style was called Karl Johansstil after King Charles XIV John. The main architects of this time, Fredrik Blom and Carl Christoffer Gjörwell, both worked for the military. Because of the general slowdown, few other buildings were constructed. On average, only ten smaller homes were built each year. The city's ambitious plans from the 1600s could easily handle these small additions.

In the late 1700s, people's actual income dropped. It reached its lowest point in 1810, being about half of what it was in the 1730s. Public officials were the most affected. Norrköping became Sweden's biggest manufacturing city. Gothenburg grew into the main trading port because it was located on the North Sea.

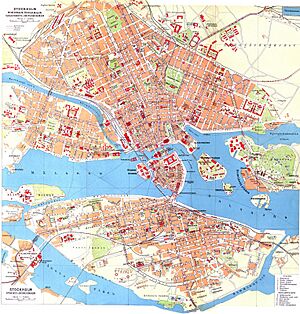

Most people still lived within the current Old Town, with some growth along the eastern shore. The population also grew on the surrounding hills. This was more noticeable in the wealthy Norrmalm district and less so in the poor Södermalm district. However, many of the hills around the city were slums. They were mostly rural, without water or sewage, and often hit by cholera.

Late Industrial Era (1850–1910)

In the second half of the 1800s, Stockholm became economically strong again. New industries appeared, and Stockholm turned into an important center for trade and services. It also became a key entry point within Sweden.

Steam engines were first used in Stockholm in 1806 at the Eldkvarn mill. But it wasn't until the mid-1800s that industrialization really took off. Two factories, Ludvigsberg and Bolinder, built in the 1840s, were followed by many others. The economic growth that came after led to about 800 new buildings being constructed between 1850–70. Many of these were in the Klara district. They were later torn down during the Redevelopment of Norrmalm from 1950–70.

During the 1850s and 1860s, gas works, sewage systems, and running water were introduced. Many streets were paved, including Skeppsbron and Strandvägen. The railway connected Stockholm closer to Europe. This also led to the creation of the first suburb, Liljeholmen, where railway workshops were located. As the railway extended north, Stockholm Central Station opened in 1871. The first horse-pulled trams started in 1877. Long before the railway, steam engines became common on boats. This led to many summer homes being built around Stockholm. But the booming city growth was also clear in central Stockholm. Several grand Neo-Renaissance buildings were built, including the Academy of Music and Södra Teatern.

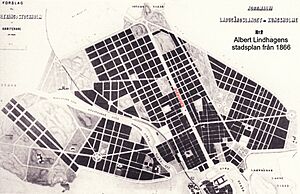

In 1866, a group led by Albert Lindhagen created a city plan for the hills (malmarna). This plan aimed to give citizens light, fresh air, and access to nature through parks and green areas. To do this, he suggested a system of wide streets, or esplanades. The most important was Sveavägen, a 2 km long and 70 m wide boulevard inspired by Champs Elysées. From 1877–80, new city plans for central Stockholm were finally approved. This prepared the city for the huge expansion that followed. In the 1880s, over 2,000 buildings were added on the hills. The population grew from 168,000 to 245,000. By the end of the century, less than 40% of residents were born in Stockholm.

Most of this housing demand was met by private builders who built just to make money. However, street width and building heights were strictly controlled by the new city plans. This made sure the city had a consistent look. A trend started by the Bünsow House at Strandvägen. The 1880s saw many grand brick buildings, including Gamla Riksarkivet and the Norstedt Building on Riddarholmen. Before the end of the decade, most new buildings had electricity, and telephones became more common. In the 1890s, the Neo-Renaissance plaster style was replaced by brick and natural stone buildings. These were largely inspired by French Renaissance architecture.

Outside the city's customs area, around the factories, shacks with terrible living conditions appeared. However, before the end of the century, these areas became official municipal societies. This made it easier to control health and construction. By the turn of the century, the city had grown far beyond its old limits. New villa suburbs were started by individuals, mixing purely speculative buildings with more quality designs. The new century brought Art Nouveau with the Central Post Office Building by Boberg (1898–1904). It also brought Neo-Baroque with the Riksdag (1894–1906). Throughout the 1910s, trams were electrified, and cars began to drive on Stockholm's streets.

During this time, Stockholm also grew as a center for culture and education. In the 1800s, several scientific institutes opened in Stockholm, such as the Karolinska Institutet. The General Art and Industrial Exposition, a big international exhibition, was held on the island of Djurgården in 1897.

20th Century Stockholm

In the late 1900s, Stockholm became a modern city with advanced technology and many different cultures. Throughout the century, many industries changed. They moved away from jobs that needed a lot of manual labor. Instead, they focused on high-technology and service jobs that required more knowledge.

The city continued to grow, and new areas were created. Some of these areas had many immigrants. At the same time, the inner city (Norrmalm) went through a period of modernization after the war. This project, called the Redevelopment of Norrmalm, was both criticized and admired. It made sure the city's center would remain the political and business hub for the future.

In 1923, the Stockholm city government moved into a new building, the Stockholm City Hall. The Stockholm International Exhibition was held in 1930. In 1967, the city of Stockholm became part of Stockholm County.

See also

- Timeline of Stockholm history

- Gamla stan

- History of Sweden

- History of Uppland

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |