History of education in the Southern United States facts for kids

The history of education in the Southern United States looks at schools, ideas, and leaders from the first colonies up to the year 2000. It covers all Southern states and includes different groups of people, like boys and girls, and various racial and ethnic groups.

Contents

Early Schools (Before 1800)

In the early days, around the Chesapeake Bay area, some basic schools started. In the late 1600s, Catholic groups ran schools for Catholic students in Maryland. Rich families often hired private teachers called tutors for their children. Some even sent their sons to schools in England or Scotland.

In 1620, a man named George Thorpe sailed to Virginia. He planned to set aside land for a university and a school for Native Americans. Sadly, these plans stopped when Thorpe was killed in 1622. In Virginia, local churches sometimes provided basic schooling for poor children. Most wealthy parents taught their children at home with tutors or sent them to small private schools.

In the Deep South, like Georgia and South Carolina, private teachers ran most schools. These were often called "old field schools." They were small, private schools built on old farm fields and usually ran for about three months a year. By 1770, Georgia had at least ten grammar schools, many taught by church ministers. The Bethesda Orphan House also educated children. Many private teachers advertised their services in newspapers. Studies show that many women in areas with schools could read and write. In South Carolina, many school projects were advertised starting in 1732. However, fewer people could read and write in the South compared to New England.

Education in the 1800s

After 1800, states like Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina started small public universities. At first, these schools were not very good, and many rich families still sent their sons to colleges in the North. In Georgia, public county academies for white students became more common. After 1811, South Carolina started a statewide system of "free schools." Here, white children could learn reading, writing, and math for free. Other Southern states copied this idea. Before the Civil War, these became the main way to organize basic "poor schools."

In the early 1800s, school conditions were still tough. Textbooks were rare, and homework or exams were not common. Teachers usually had only a year or two of schooling after 8th grade. Many schools used the "Lancasterian system." In this system, one paid teacher taught a few older students. These older students then taught the younger ones, often by having everyone recite lessons together.

Calvin H. Wiley (1819–1887) was a key figure in North Carolina. For 12 years, he worked to create a modern public education system in the region. He started the state education association and helped set up training for teachers. He also created standards and tests for teachers and made annual teacher certification a rule. Wiley organized county school systems with superintendents and boards. He believed that education for everyone would help the state's economy grow.

After the Civil War, during the Reconstruction era, new governments in the South rebuilt public school systems. They used taxes to pay for these schools. For the first time, both white and Black children could get an education paid for by the state. However, lawmakers agreed that schools would be separate for white and Black students. Only a few schools in New Orleans allowed both groups to learn together.

After white Democrats took back control of state governments, they often gave much less money to public schools for Black students. This continued until the 1940s. However, many private schools for Black students received money from wealthy people and groups in the North well into the 1900s. Groups like the American Missionary Association, the Peabody Education Fund, the Jeanes Fund, the Slater Fund, the Rosenwald Fund, the Southern Education Foundation, and the General Education Board (funded by the Rockefeller family) provided important support.

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court ruled that state laws creating separate public schools for Black and white students were against the law. This famous case was called Brown v. Board of Education.

In rural areas, public schooling usually stopped after elementary grades for both white and Black students. This was often called "eighth grade school."

Education in the 1900s

After 1900, some cities began to open high schools, mostly for white middle-class students. In the 1930s, about a quarter of Americans still lived and worked on farms. Few rural Southerners, both white and Black, went beyond 8th grade until after 1945.

Black Education

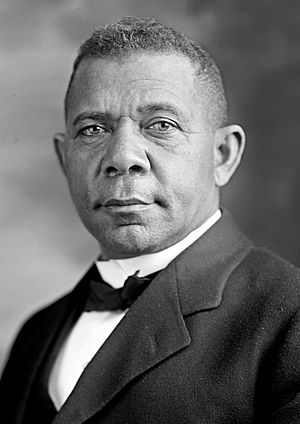

Booker T. Washington was a very important Black leader in education and politics from the 1890s until his death in 1915. Washington led his own college, Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. His advice and connections helped many other Black colleges and high schools, mostly in the South. This was where most Black people lived before the Great Migration. Washington was a trusted advisor to major charities like the Rockefeller and Rosenwald foundations, which gave money to leading Black schools. The Rosenwald Foundation helped build schools for rural Black students in the South.

Washington believed in practical education. He said, "We need not only the industrial school, but the college and professional school as well." He felt that Black teachers, ministers, lawyers, and doctors would do well if they had skilled workers around them. Washington strongly supported reforms that focused on science, industry, and farming. This type of education helped many Black teachers, professionals, and workers build successful careers. He tried to work within the system and did not openly protest against the segregated Jim Crow laws. However, Washington secretly used his network to fund many legal challenges by the NAACP against laws that stopped Black people from voting.

Changes in Atlanta Schools

In many American cities, reformers looked for ways to improve schools and stop waste. They wanted experts to run the schools. For example, in 1897, Atlanta reformed its schools. The school board became smaller, which reduced the power of local politicians. School board members were elected by the whole city, which lessened the influence of special groups. The superintendent's power increased. Buying supplies in bulk saved money. Standards for hiring teachers became the same for everyone. New ideas for what students learned were also introduced. These changes aimed to create a school system for white students that followed the best practices of the time.

The Great Depression's Impact

The Great Depression, a time of severe economic hardship, greatly affected education in the South. School attendance dropped because local school districts faced money problems. High unemployment and pay cuts meant less tax money for schools. Many business leaders pushed for lower taxes, which further hurt school budgets.

By early 1934, almost 20,000 schools across the country had closed. The problem was worse in the South. Schools either closed or had shorter school years because they could not pay teachers or cover costs. Black students faced racism, poverty, and neglect, and were hit especially hard. In 1932, 230 Southern counties had no high schools for Black students. The Depression changed teachers' working conditions and damaged school programs they had worked hard to build. However, many young people stayed in school because there were very few jobs available.

Different Groups in Education

For Black people, women, and poor white people, education was often "separate and unequal" until the late 1900s.

More young women started becoming teachers in the Northeast first. In Massachusetts, 78% of teachers were women by 1860. The South was slower to change. In Virginia, 34% of white teachers were women in 1870, and 69% by 1900. Only 24% of Black teachers were women in 1870, rising to 54% by 1900. For Black men who stayed in the rural South, teaching was one of the few respected jobs they could get.

Black Students and Schools

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) was an English church group that sent missionaries to the colonies. They educated white children and also tried to teach enslaved people. Their goal was to teach them to read the Bible and other useful books, learn church teachings, and use prayers. Writing was also taught so children could get useful jobs. Teachers also wanted students to behave well outside of school.

With the owners' permission, the SPG also opened schools for enslaved people in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Maryland. The church leaders said that becoming Christian would not make a slave free. Slave owners thought that better-behaved enslaved children would cause less trouble. Reports from South Carolina showed that hundreds of enslaved people, including adults, wanted to learn. The SPG started the Charleston Negro School in 1742. It used well-trained ten-year-old enslaved children to teach older people. The school aimed to create a lasting Christian community among enslaved people, where they could read and be religious. By 1743, 45 children were taught during the day and 15 adults in the evening. The school did well until 1764, when its leaders died and funding from London stopped. After that, there was no formal schooling for Black people in the South until the Civil War.

After the Civil War, during the early Reconstruction era, the new Freedmen's Bureau opened 1,000 schools across the South for Black children. This built on schools already started in camps for formerly enslaved people. Freedmen (formerly enslaved people) were very eager for schooling for both adults and children. Many signed up, and they were very enthusiastic. The Bureau spent $5 million to set up these schools. By the end of 1865, over 90,000 freedmen were students. The schools taught subjects similar to those in Northern schools.

Many teachers from the Freedmen's Bureau were well-educated women from the North. They were motivated by their religious beliefs and their opposition to slavery. About half the teachers were white Southerners, one-third were Black, and one-sixth were white Northerners. Most were women, but among African Americans, there were slightly more male teachers than female teachers. In the South, people were drawn to teaching because of the good salaries during a time when the economy was struggling. Northern teachers were often paid by Northern groups and wanted to help the freedmen. Only the Black teachers showed a strong commitment to racial equality, and they were also the most likely to continue teaching.

When Republicans gained power in the Southern states after 1867, they created the first public school systems funded by taxes. Black Southerners wanted public schools for their children, but they did not ask for schools where races were mixed. Almost all the new public schools were separate, except for a few in New Orleans. After Republicans lost power in the mid-1870s, conservative white leaders kept the public school systems but greatly cut their funding.

Almost all private colleges in the South kept Black and white students separate. Berea College in Kentucky was the main exception until a state law in 1904 forced it to separate students by race. The American Missionary Association helped start and develop several historically black colleges, such as Fisk University and Shaw University.

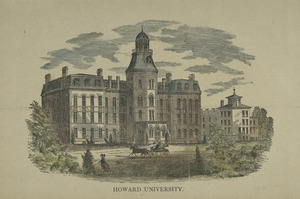

Northern churches and their missionary groups started private schools across the South to provide high school education. They also offered some college-level courses. Tuition was very low, so churches supported these colleges financially and helped pay teachers. In 1900, Protestant churches, mostly from the North, ran 247 schools for Black students across the South. They had a budget of about $1 million, employed 1,600 teachers, and taught 46,000 students. Important schools included Howard University (a federal school in Washington), Fisk University in Nashville, Atlanta University, and Hampton Institute in Virginia. Most new colleges in the 1800s were founded in Northern states.

In 1890, Congress expanded a program to include federal money for state-supported colleges across the South. To get this money, states had to have colleges for both Black and white students. This law, called the second Morrill Land-Grant Act, gave more higher education chances for African Americans. However, it also encouraged separate schools for different races.

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute was very important because it set the standards for "industrial education." Booker T. Washington, who graduated from Hampton, founded the important Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers in 1881. Washington promoted industrial education for African Americans because it was practical. In contrast, W.E.B. DuBois believed it was important for African Americans to prove they were equal to whites by succeeding in traditional college programs. In 1900, few Black students were in college because their schools lacked staff and money, and students often needed extra help. Graduates of schools like Hampton became high school teachers. However, some HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), like Howard University, Fisk University, and Atlanta University, had standard college programs.

While colleges and academies generally taught both boys and girls, historians did not pay much attention to the role of women as students and teachers until the late 1900s.

Higher Education

The South was slow to develop colleges and universities compared to the North and Europe. The College of William & Mary was founded by the Virginia government in 1693. It received a large amount of land and a tax on tobacco to help pay for it. It was closely connected to the Anglican Church. James Blair, a leading Anglican minister, was its president for 50 years. The college was strongly supported by Virginia's wealthy landowners, most of whom were Anglicans. After the state capital moved to Richmond, the town and the college quickly became less important.

William and Mary's founding document also included educating Native American children. So, it created an Indian School. Its main goal was to teach Native American students to read and write enough to become missionaries to their own people.

Professional Training

In the 1900s, training for jobs like law, medicine, religion, business, and teaching usually meant going to special schools after finishing college. This type of training grew slowly in the South. Virginia's College of William & Mary hired the first law professors. They trained many lawyers, politicians, and important landowners. George Wythe (1726?–1806), who signed the Declaration of Independence, taught a one-year law course at William and Mary starting in 1779. He gave lectures and set up mock courts. His students included famous figures like Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, James Monroe, and James Madison. He retired in 1790 and was replaced by St. George Tucker.

See also

- Education in Alabama

- Education in Arkansas

- Education in Florida

- Education in Georgia

- History of education in Kentucky

- Education in Louisiana

- Education in Mississippi

- History of education in Missouri

- Education in North Carolina

- Education in Oklahoma

- Education in South Carolina

- Education in Tennessee

- Education in Texas

- Education in Virginia

- Education in West Virginia

- Antebellum South

- History of the Southern United States

- History of education in the United States

- Southern Education Board

- Historically black colleges and universities

- School segregation in the United States

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |