W. E. B. Du Bois facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

W. E. B. Du Bois

|

|

|---|---|

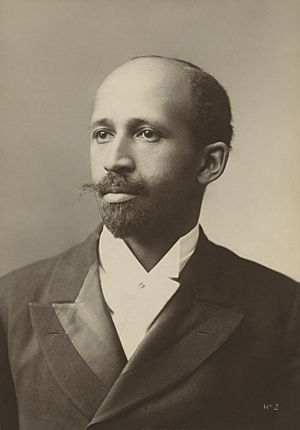

Carte de visite by James E. Purdy, 1907

|

|

| Born |

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois

February 23, 1868 |

| Died | August 27, 1963 (aged 95) Accra, Ghana

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 2, including Yolande |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal 1920 Lenin Peace Prize 1959 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | Atlanta University NAACP |

| Thesis | The Suppression of the African Slave-trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870 (1896) |

| Doctoral advisor | Albert Bushnell Hart |

| Influences | |

| Signature | |

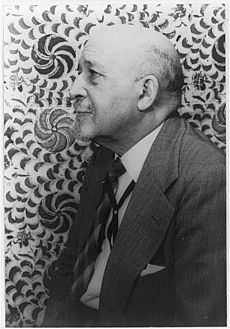

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (pronounced dew-BOYSS; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an important American leader. He was a sociologist (someone who studies society), a historian, and a Pan-Africanist. He worked hard for civil rights for all people. Du Bois fought against unfair treatment and for equality in the United States and around the world.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868. His hometown was Great Barrington, Massachusetts. This community was quite open-minded for its time. Most people there were white, but they treated Du Bois well.

He went to the local public school, which included students of all races. He played with his white classmates. His teachers saw how smart he was and encouraged him to study. This good experience made him believe that learning could help African Americans gain power and respect.

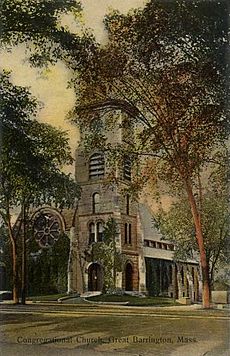

After graduating from Searles High School, Du Bois wanted to go to college. The people from his childhood church, the First Congregational Church of Great Barrington, helped him. They raised money to pay for his college tuition.

Du Bois went on to study at top universities. He graduated from the University of Berlin and Harvard University. He was the first African American to earn a doctorate degree from Harvard. Later, he became a professor at Atlanta University. He taught history, sociology, and economics.

Fighting for Rights

Du Bois was a strong voice against unfair practices. He spoke out against lynching (when a mob kills someone, often by hanging, without a trial). He also fought against Jim Crow laws, which were unfair laws that kept Black people separate and unequal. He protested against discrimination in schools and jobs.

In 1909, Du Bois helped start the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This group worked to end racial discrimination.

Before the NAACP, Du Bois was a leader of the Niagara Movement. This group of African-American activists wanted equal rights for Black people. Du Bois and his supporters did not agree with the Atlanta Compromise. This was an idea from Booker T. Washington. It suggested that Black people in the South should work and accept white political rule. In return, white people would offer basic education and job chances.

Du Bois believed in full civil rights and more political power for Black people. He thought that educated African Americans, whom he called the "the Talented Tenth", would lead this change. He felt that Black people needed good education to develop strong leaders.

His fight for justice included all people of color. He especially cared about Africans and Asians living in colonies ruled by European countries. He supported Pan-Africanism, a movement to unite people of African descent worldwide. He helped organize several Pan-African Congresses. These meetings aimed to help African colonies gain independence from European rule. Du Bois traveled to Europe, Africa, and Asia many times. After World War I, he studied how Black American soldiers were treated in France. He showed how much prejudice and racism existed in the U.S. military.

Important Writings

Du Bois wrote many books and essays. His book, The Souls of Black Folk, is a very important work in African-American literature. In 1935, he wrote Black Reconstruction in America. This book challenged the idea that Black people were to blame for the problems after the Civil War.

He often used the term "color line" to describe the unfairness of "separate but equal" laws. These laws were common in American society. He started The Souls of Black Folk by saying, "The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line." This was a main idea in his life's work.

His 1940 autobiography, Dusk of Dawn, is seen as one of the first scientific studies in American sociology. He wrote two other life stories, all with essays on society, politics, and history. He was also the editor of the NAACP's magazine, The Crisis. He published many important articles there.

Du Bois believed that capitalism (an economic system based on private ownership) caused racism. He often supported socialist ideas throughout his life. He was also a strong peace activist. He spoke out for nuclear disarmament, which means getting rid of nuclear weapons. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which brought many of the changes Du Bois fought for, became law a year after he died.

Later Years

In 1945, Du Bois was part of a group from the NAACP that went to a meeting in San Francisco. This meeting created the United Nations. The NAACP wanted the United Nations to support racial equality and end the colonial era. China, India, and the Soviet Union supported this idea. But other major countries mostly ignored it. The NAACP's ideas were not put into the final United Nations Charter.

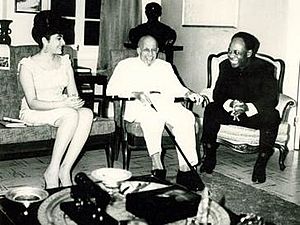

Later in 1945, Du Bois went to the last Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England. This meeting was very successful. There, Du Bois met Kwame Nkrumah, who would become the first president of Ghana. Nkrumah later invited Du Bois to live in Africa.

Du Bois also helped send requests to the UN about unfair treatment of African Americans.

He was always against war, but his efforts grew stronger after World War II. In 1949, he spoke at a peace conference in Paris. He also traveled to Moscow to speak at a peace conference there.

During the 1950s, the U.S. government started a campaign against communism called McCarthyism. Du Bois was targeted because he had socialist views. The government investigated him for possible "subversive activities."

In 1950, Du Bois became the head of the new Peace Information Center (PIC). This group worked to share the Stockholm Peace Appeal in the United States. The appeal asked governments to ban all nuclear weapons. The U.S. Justice Department said the PIC was acting for a foreign country. They wanted the PIC to register with the government. Du Bois and other PIC leaders refused. They were charged with not registering.

His trial was in 1951. The case was stopped before the jury decided. This happened when his lawyer said that Albert Einstein would speak for Du Bois. Even though he was not found guilty, the government took away Du Bois's passport. He did not get it back for eight years.

In 1958, Du Bois got his passport back. He traveled the world with his second wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois. They visited the Soviet Union and China and were welcomed warmly. Du Bois later wrote good things about these countries.

Death in Africa

Du Bois went back to Africa in late 1960. He attended the inauguration of Nnamdi Azikiwe, the first African governor of Nigeria.

While in Ghana in 1960, Du Bois talked with its president, Kwame Nkrumah. They discussed creating a new encyclopedia about the African diaspora (people of African origin living outside Africa). It would be called the Encyclopedia Africana. In October 1961, at 93 years old, Du Bois and his wife moved to Ghana to start work on the encyclopedia.

In early 1963, the United States would not renew his passport. So, Du Bois decided to become a citizen of Ghana. This was a symbolic act. While he intended to give up his U.S. citizenship, he never officially did.

Du Bois's health got worse during his two years in Ghana. He died on August 27, 1963, in Accra, Ghana's capital. He was 95 years old.

Ghana held a state funeral for Du Bois on August 29–30, 1963. This was at President Nkrumah's request. He was buried near Christiansborg Castle, which was the government's main building. In 1985, another ceremony honored Du Bois. His body was moved to his former home in Accra, along with the ashes of his second wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois. This home is now the W. E. B. Du Bois Memorial Centre for Pan African Culture.

Personal Life

Du Bois was a very organized and disciplined person. He woke up early, worked all day, and read in the evenings. He planned his schedules carefully. Many people found him to be serious and formal. He always wanted to be called "Dr. Du Bois."

He was not very outgoing, but he had close friends. These included Charles Young, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and Albert Einstein. His closest friend was Joel Elias Spingarn, a white man. But Du Bois never called him by his first name.

Du Bois dressed formally and carried a walking stick. He was about 5 feet 5.5 inches (166 cm) tall. He always had a neat mustache and goatee. He enjoyed singing and playing tennis.

Du Bois married Nina Gomer in 1896. They had two children. Their son, Burghardt, died as a baby. Their daughter, Yolande, became a high school teacher. Her father encouraged her to marry Countee Cullen, a famous poet. They divorced after two years. Yolande married again and had a daughter, who was Du Bois's only grandchild. This marriage also ended in divorce.

After Nina died in 1950, Du Bois married Shirley Graham in 1951. She was an author, playwright, and activist. She had a son named David Graham, who became close to Du Bois and took his last name. David also worked for African-American causes.

Beliefs

As a child, Du Bois went to a Congregational church. But he stopped being part of organized religion when he was in college. As an adult, Du Bois said he was agnostic (meaning he wasn't sure if God exists) or a freethinker. Some people thought he was an atheist (someone who does not believe in God).

Even though he wasn't personally religious, he used religious symbols in his writings. Many people at the time saw him as a wise leader or "prophet."

Honors and Legacy

Du Bois received many honors for his work:

- In 1920, the NAACP gave him the Spingarn Medal.

- In 1959, he received the International Lenin Peace Prize from the USSR.

- In 1969, the W. E. B. Du Bois Research Institute was started at Harvard University.

- The place where Du Bois grew up in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, became a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

- The United States Postal Service honored Du Bois with his picture on a postage stamp in 1992 and again in 1998.

- In 1994, the main library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst was named the W. E. B. Du Bois Library.

- Since 2000, Harvard's Hutchins Center for African and African American Research has given the W. E. B. Du Bois Medal. This is Harvard's highest honor in African and African American studies.

- Dormitories at the University of Pennsylvania and Hampton University are named after him.

- The Encyclopedia Africana was inspired by and dedicated to Du Bois.

- Humboldt University in Berlin has a lecture series named in his honor.

- In 2005, Du Bois was honored with a medallion in The Extra Mile in Washington D.C. This memorial honors important American volunteers.

- The highest award from the American Sociological Association was renamed the W.E.B. Du Bois Career of Distinguished Scholarship Award in 2006.

- In 2013, a bust (a sculpture of his head and shoulders) of Du Bois was placed at Clark Atlanta University.

- The Du Bois Orchestra at Harvard was founded in 2015.

- Du Bois was shown as a character in the 2020 Netflix show Self Made.

Selected Works

Du Bois wrote many important books and essays. Here are some of them:

- The Philadelphia Negro (1899)

- The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

- "The Talented Tenth" (1903)

- John Brown: A Biography (1909)

- The Negro (1915)

- Black Reconstruction in America (1935)

- Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil (1920)

- Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept (1940)

- The Autobiography of W. E. Burghardt Du Bois (1968)

- The Quest of the Silver Fleece (1911) (a novel)

- Dark Princess: A Romance (1928) (a novel)

He also edited The Crisis magazine from 1910 to 1933. Many of his strong arguments were published there.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: W. E. B. Du Bois para niños

In Spanish: W. E. B. Du Bois para niños