History of laws concerning immigration and naturalization in the United States facts for kids

The United States didn't always have strict rules about who could move here. For a long time, there were no formal immigration laws. However, there were clear rules about becoming a citizen, which is called naturalization. Only people who went through this process and became citizens could vote or hold public office. This system, where people could move to the U.S. freely but becoming a citizen was carefully controlled, lasted until the late 1800s. Around that time, new ideas about "racial purity" led the government to create immigration laws. These laws aimed to stop the open immigration policy that the country's founders had allowed.

Contents

Early Laws: The 18th Century

The Constitution of the United States was approved on September 17, 1787. It gave the United States Congress the power to create rules for naturalization.

In 1790, Congress passed the first naturalization law. This law allowed people to apply for citizenship if they had lived in the country for two years and in their current state for one year. But there was a big catch: only "free white persons" who were considered to have "good moral character" could become citizens. For over 100 years, almost any federal or state court could naturalize someone.

Later, the Naturalization Act of 1795 changed the rules. It required people to live in the U.S. for five years and give a three-year notice before applying. The Naturalization Act of 1798 made it even harder, requiring 14 years of residency and five years' notice.

Changes in the 19th Century

The Naturalization Law of 1802 replaced the strict 1798 law.

A very important change came in 1868 with the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment was created to give citizenship to former slaves. It says that "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States." This means that if you are born in the U.S., you are a citizen, with a few exceptions like children of diplomats. The Supreme Court confirmed this in the 1898 case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, which involved the child of Chinese citizens living legally in the U.S.

In 1870, the law was updated to allow African Americans to become naturalized citizens. However, Asian immigrants were still not allowed to become citizens, even though they could live in the U.S. In some states, like California, non-citizen Asians couldn't even own land.

The first federal law to limit immigration was the Page Act, passed in 1875. It aimed to stop "undesirable" immigrants. This included people from East Asia who were forced laborers, and anyone who was a convicted criminal in their home country. In reality, this law mostly prevented Chinese women from entering the U.S.

After many Chinese immigrants came to the Western United States in the 1850s-1870s, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Chinese people had come to work on railroads and during the Gold Rush in California. This act stopped Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S. for ten years. It was the first immigration law passed by Congress. The act was renewed several times and finally ended in 1943.

The 20th Century: New Rules and Quotas

By the early 1900s, it was clear that having many different courts handle naturalization led to confusion. So, the Naturalization Act of 1906 created a new federal agency to keep records and make sure naturalization procedures were the same across the country.

In 1907, the Empire of Japan and the U.S. made an agreement called the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907. Japan agreed to stop giving passports to its citizens who wanted to move to the U.S. However, many Japanese still came to Hawaii and then moved to the U.S. mainland. Many Japanese men came to work, and later, "postcard wives" (women who married men they only knew from pictures) came to join them.

Congress also started banning people for health reasons or lack of education. A law in 1882 banned people with mental illness or infectious diseases. After President William McKinley was assassinated by someone whose parents were immigrants, the Anarchist Exclusion Act of 1903 was passed to keep out known anarchists. A literacy test was added in the Immigration Act of 1917.

1920s: Quotas and Restrictions

In 1921, Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act. This law set limits on how many immigrants could come from each country. The limits were based on how many people from each country were already living in the U.S. in 1910.

A very important Supreme Court case in 1923, United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, officially decided that South Asian Indians were not "white." This meant that many Indians who had already become citizens had their citizenship taken away. Laws in California also prevented non-citizens from owning land, which affected many Indian Americans.

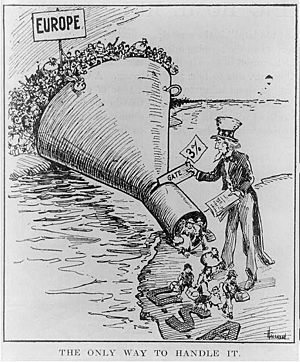

The Immigration Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act) created an even stricter quota system. It set limits for immigrants from the Eastern Hemisphere and basically stopped all immigration from Asia. It used the 1890 census, which greatly reduced the number of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe.

1930s–1950s: Depression and War

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, immigration to the U.S. dropped sharply. Many people, including between 500,000 and 2 million Mexican Americans (most of whom were citizens), were forced to return to Mexico.

The Chinese exclusion laws were finally ended in 1943. In 1946, the Luce–Celler Act of 1946 ended discrimination against Indian Americans and Filipinos, allowing them to become citizens and setting a small quota for their immigration.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (the McCarran-Walter Act) changed the quotas again, using the 1920 census. For the first time, racial differences were removed from the law. However, most of the immigration spots still went to people from Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Germany.

1960s: Ending National Quotas

The Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965 (the Hart-Celler Act) was a major change. It got rid of the old system that favored certain countries. For the first time, there were limits on immigration from the Western Hemisphere. The law also changed who got priority for immigration. It gave preference to immigrants with skills needed in the U.S., refugees, and family members of U.S. citizens. Bringing families together became a main goal of the law.

1980s: Refugees and Control

The Refugee Act of 1980 created new policies for refugees, following rules set by the United Nations. A goal was set for 50,000 refugees each year, and the total number of immigrants allowed worldwide was reduced.

In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) was passed. This law made it illegal for employers to knowingly hire undocumented immigrants and set penalties for doing so. IRCA also offered a chance for about 3 million undocumented immigrants already in the U.S. to become legal residents. It also increased the activities of the United States Border Patrol.

1990s: More Changes and Enforcement

From 1990 to 1997, the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform studied immigration policy. It suggested improvements for border control and recommended an automated system to check if workers were legal. It also said that immediate family members and skilled workers should get priority for immigration.

The Immigration Act of 1990 (IMMACT) expanded the 1965 act. It significantly increased the total number of immigrants allowed to 700,000 per year and increased visas by 40 percent. Family reunification remained the main reason for immigration, with more opportunities for employment-based immigration.

This act also changed who was in charge of naturalizing people. Before, courts did it, but the actual work was done by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. After October 1, 1991, the power to naturalize people was given to the United States Attorney General, who then gave it to the Immigration and Naturalization Service. However, naturalization ceremonies are still often held in federal courthouses.

In 1996, several laws were passed that made policies stricter for both legal and undocumented immigrants. The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA) and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) greatly increased the types of criminal activities that could lead to deportation, even for green card holders. These laws also made mandatory detention common for certain deportation cases. As a result, over 2 million people have been deported since 1996.

The 21st Century: Security and Reform Debates

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, greatly changed how Americans viewed immigration. The terrorists involved had entered the U.S. on tourist or student visas, and some had broken the rules of their visas. These attacks showed weaknesses in the U.S. immigration system, especially in visa processing and information sharing.

The REAL ID Act of 2005 changed some visa limits, made asylum applications stricter, and made it easier to keep out suspected terrorists. It also removed restrictions on building border fences.

In 2005, Senators John McCain and Ted Kennedy proposed the Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act. This bill aimed to address many immigration issues, including legalizing some undocumented immigrants, creating guest worker programs, and improving border security. This bill was not passed, but parts of it were included in later proposals.

In 2006, the House of Representatives and the Senate each passed their own different immigration bills. The House bill focused only on enforcement at the border and within the country. The Senate bill would have offered a path to citizenship for many undocumented immigrants and increased legal immigration. However, they could not agree on a final bill.

In 2007, another bill, the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, was discussed in the Senate. It also aimed to provide a path to citizenship for many undocumented immigrants, increase legal immigration, and improve enforcement. This bill also failed to pass.

Some parts of these larger reform plans have been introduced as separate bills. For example, the DREAM Act, first proposed in 2001, would give legal residency and a path to citizenship to undocumented immigrants who graduate from U.S. high schools and attend college or join the military.

Currently, Congress sets immigrant visa limits at 700,000 for categories like employment, family preference, and immediate family. There are also visas for diversity and a small number of special cases. In recent years, the number of immigrants in these categories has been close to the maximum allowed.

The number of people becoming naturalized citizens has varied from about 500,000 to over 1,000,000 per year since the early 1990s. This number is often higher than the number of visas issued in those years because many people who received amnesty in 1986 have since become citizens. Generally, immigrants can apply for citizenship after five years of living in the U.S.

These numbers are separate from illegal immigration. While the government doesn't publish data on pending applications, there are huge backlogs for certain visa categories, especially for adult children and siblings from countries like Mexico and the Philippines.

It's important not to confuse legal immigration visas with temporary work permits. Permits for seasonal workers or students usually do not allow people to become permanent residents. Even those with temporary work visas (like H1-B workers) must apply for permanent residence separately.

Arizona SB 1070 (2010)

In 2010, Arizona passed a law called SB 1070. This law made it a state crime for immigrants not to carry their immigration documents. It also allowed state police to check a person's immigration status if they were stopped or arrested for any reason. The law also made it illegal to shelter, hire, or transport an undocumented immigrant.

Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act (2013)

On April 17, 2013, a group of eight senators, known as the "Gang of Eight", introduced a new immigration reform bill called S.744. The Senate passed this bill on June 27, 2013. However, the House of Representatives did not vote on it, so it did not become law.

Presidential Actions

On November 21, 2014, President Barack Obama signed two executive actions. These actions aimed to delay deportation for millions of undocumented immigrants. They applied to parents of U.S. citizens (called Deferred Action for Parents of Americans) and young people who were brought to the country illegally as children (called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals).

For more recent actions, you can look at Immigration policy of Donald Trump.

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |