History of the Assyrians facts for kids

The history of the Assyrians is a story that stretches over five thousand years. It begins with the ancient civilization of Assyria in Mesopotamia and continues with the history of the Assyrian people after their empire fell. Assyria was one of the world's first great empires, known for its powerful armies, amazing art, and incredible cities.

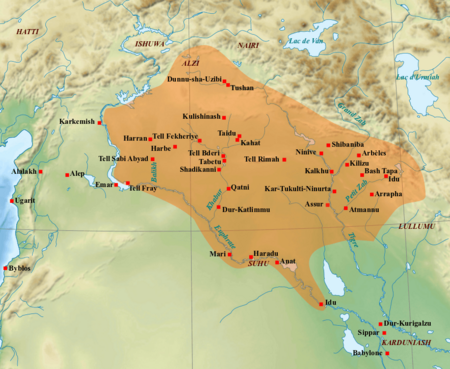

Assyria got its name from its first capital city, Assur, which was founded around 2600 BC. For a long time, Assur was ruled by other powerful cities. But around 2025 BC, it became an independent city-state. Over many centuries, Assyria grew from this single city into a mighty empire.

Historians divide ancient Assyrian history into several periods:

- Early Assyrian period (c. 2600–2025 BC)

- Old Assyrian period (c. 2025–1364 BC)

- Middle Assyrian period (c. 1363–912 BC)

- Neo-Assyrian period (911–609 BC)

- Post-imperial period (609 BC–c. AD 240)

Even after the empire ended in 609 BC, the Assyrian people and their culture continued. They adopted Christianity and played an important role in the history of the Middle East. Today, many Assyrians live all over the world, but they still work to keep their ancient language and traditions alive.

Contents

Ancient Assyria (2600 BC – AD 240)

Early and Old Assyrian Periods (2600–1364 BC)

The story of Assyria begins with the city of Assur. It was built on a hill next to the Tigris river, a great location for defense and trade. In its early days, Assur was a small but important religious center. It was ruled by bigger empires from southern Mesopotamia, like the Akkadian Empire.

Around 2025 BC, Assur became an independent city-state ruled by its own kings. These early rulers didn't call themselves "kings." Instead, they used the title "governor," believing that the city's true king was their main god, also named Ashur.

During the Old Assyrian period, the city of Assur became a major center for trade. Assyrian merchants created a large trading network. They set up colonies in other lands, like Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). Archaeologists have found thousands of clay tablets in these colonies. These tablets were business letters that tell us a lot about their trade.

Around 1808 BC, a powerful Amorite king named Shamshi-Adad I conquered Assur. He created a large kingdom in northern Mesopotamia. After his death, his kingdom fell apart, and for a while, Assyria was controlled by other powers, including Babylonia and the kingdom of Mitanni.

Middle Assyrian Period (1363–912 BC)

Around 1363 BC, Assyria broke free from Mitanni rule. Under King Ashur-uballit I, Assyria began to grow into a powerful kingdom. This was the start of the Middle Assyrian Empire. Ashur-uballit was the first Assyrian ruler to call himself "king" (šar). He wanted to be seen as an equal to the great kings of Egypt and the Hittites.

A series of strong warrior-kings, like Adad-nirari I, Shalmaneser I, and Tukulti-Ninurta I, expanded the empire. They conquered new lands and made Assyria one of the great powers of the ancient world. For a short time, Tukulti-Ninurta I even conquered Babylonia, Assyria's great rival to the south. He also built a new capital city named Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta.

After Tukulti-Ninurta I was killed, Assyria went through a period of decline. The empire shrank, and it faced attacks from groups like the Arameans. However, even during these tough times, the Assyrian army remained strong. By the end of this period, King Ashur-dan II began to win back lost lands, setting the stage for Assyria's greatest era.

Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC)

The Neo-Assyrian period was when Assyria reached the height of its power. For about 300 years, it was the largest and strongest empire the world had ever seen.

The Empire at its Peak

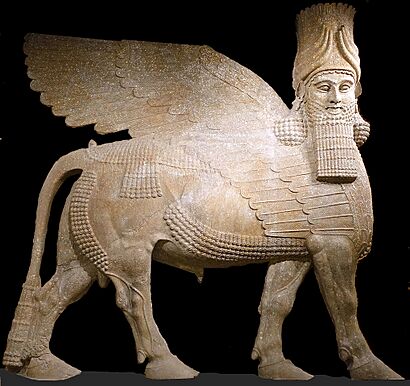

Kings like Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) led many military campaigns. They used new tactics and iron weapons to conquer vast territories. Ashurnasirpal II also built a magnificent new capital at Kalhu (also known as Nimrud).

His son, Shalmaneser III, continued to expand the empire. He fought against a coalition of western kings at the Battle of Qarqar and received tribute from many rulers, including King Jehu of Israel.

After a period of weaker rule, Tiglath-Pileser III (ruled 745–727 BC) came to the throne. He was a brilliant general and organizer. He reformed the army and the government, making the empire much more stable. He conquered many lands, including Babylonia, and is considered by many to be the true founder of the Assyrian Empire as a world power.

The Sargonid Dynasty

The last and most famous dynasty of Assyrian kings was the Sargonid dynasty.

- Sargon II (ruled 722–705 BC) was a great conqueror who founded another new capital, Dur-Sharrukin.

- Sennacherib (ruled 705–681 BC), his son, moved the capital to the ancient city of Nineveh. He turned Nineveh into a spectacular city with huge walls, beautiful palaces, and lush gardens.

- Esarhaddon (ruled 681–669 BC) expanded the empire to its greatest size. His armies marched all the way to Egypt and conquered it, a huge achievement.

- Ashurbanipal (ruled 669–631 BC) was the last great king of Assyria. He was a fierce warrior but is most famous for creating a huge library at Nineveh. It contained thousands of clay tablets on every subject, from science to literature.

The Fall of Assyria

After Ashurbanipal's death, the empire began to weaken. Years of constant warfare had drained its resources. The people they had conquered often rebelled. A civil war broke out between two of Ashurbanipal's sons, which weakened Assyria even more.

Seeing their chance, Assyria's enemies, the Babylonians and the Medes, joined forces. In 612 BC, they attacked and destroyed the capital city of Nineveh. By 609 BC, the last Assyrian resistance was defeated, and the great Assyrian Empire came to an end.

Post-Imperial Period (609 BC – AD 240)

Even though the empire was gone, the Assyrian people did not disappear. They continued to live in their homeland in northern Mesopotamia. Over the next several centuries, Assyria was ruled by other empires, including the Persians, Greeks (Seleucid Empire), and Parthians.

During the Parthian period, the region recovered. Cities like Assur were rebuilt and became important centers again. Several small, semi-independent kingdoms with Assyrian populations, such as Adiabene and Hatra, appeared. The people kept parts of their old culture alive, and some local rulers even made monuments that looked like those of the ancient Assyrian kings.

From Antiquity to the Middle Ages

The Rise of Christianity

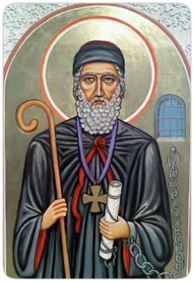

Starting in the 1st century AD, the Assyrians began to convert to Christianity. Over time, Christianity became the main religion of the Assyrian people, replacing the ancient Mesopotamian gods. They became one of the first nations to fully embrace the new faith.

The Assyrian church became known as the Assyrian Church of the East. It developed its own unique traditions and was separate from the churches in the Roman Empire. Assyrian Christians were great scholars and missionaries. They translated many important Greek works of science and philosophy into their language, Syriac. These translations later helped spark the Islamic Golden Age.

During the Sasanian Empire (240–637), the Assyrians continued to remember their ancient past. They told stories and wrote histories about famous kings like Sennacherib and Sargon II.

Life Under Muslim and Mongol Rule

In the 7th century, Arab armies conquered Mesopotamia. The Assyrians, as Christians, were allowed to practice their religion but had to pay a special tax. For many centuries, they lived peacefully and contributed greatly to the culture and science of the Islamic world.

This changed during the Mongol invasions. In the 13th century, the Mongol leader Hulagu Khan, whose wife was a Christian, was at first seen as a liberator. But later Mongol rulers converted to Islam and began to treat Christians harshly.

The worst period came in the late 14th century under the conqueror Timur. He led brutal campaigns against non-Muslims. These events were a disaster for the Assyrians. Their population was drastically reduced, and their church, which had once spread across Asia, was nearly destroyed. The survivors were forced to retreat into remote, mountainous areas of their homeland.

Modern History (1552–Present)

Ottoman Rule and Church Divisions

From the 16th century, the Assyrian homeland was part of the Ottoman Empire. During this time, a major split happened within the Church of the East. In 1552, a group of bishops who disagreed with the church leadership broke away and joined the Roman Catholic Church. This new church became known as the Chaldean Catholic Church. This division created different identities within the Assyrian people:

- Assyrians (followers of the Church of the East)

- Chaldeans (followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church)

- Syriacs (followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church)

Despite these divisions, the groups share a common heritage and language. For centuries, they lived in relative peace under the Ottoman system, which allowed religious communities to manage their own affairs.

Persecution and the Assyrian Genocide

The situation for Assyrians worsened in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the Ottoman Empire began to collapse. They faced terrible violence and hardship.

During World War I, the Ottoman government carried out a series of genocides against its Christian minorities. Alongside the Armenians and Greeks, the Assyrians suffered what they call the Sayfo (meaning "Sword"), or the Assyrian genocide. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of Assyrians were killed, and countless more were forced to flee their homes.

This tragic event led to the Assyrian diaspora, with survivors scattering across the world. It also fueled a desire for an independent and safe homeland. Assyrian leaders appealed to world powers after the war, but their dream of a state was not realized.

Contemporary Assyrians

Today, the majority of Assyrians live in diaspora communities in countries like the United States, Sweden, and Australia. They work hard to preserve their language, culture, and traditions.

In their homeland in Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran, Assyrians continue to face challenges. The rise of terrorist groups like ISIL in 2014 brought new suffering and led to the destruction of priceless ancient Assyrian heritage sites, including parts of Nineveh and Nimrud.

Despite these hardships, the Assyrian people remain resilient. They have formed their own political parties and defense forces to protect their communities. They celebrate their culture through festivals like Akitu (the Assyrian New Year) and continue to fight for their rights and the preservation of their unique, ancient heritage.

See also

- Assyrian cuisine

- Assyrian culture

- Assyrian homeland

- Assyrian music

- Assyrian struggle for independence

- History of Syriac Christianity

- List of Assyrians

- Name of Syria

- Names of Syriac Christians

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |