History of the anti-nuclear movement facts for kids

The use of nuclear technology, both for energy and as a weapon, has always been a topic of much discussion and disagreement.

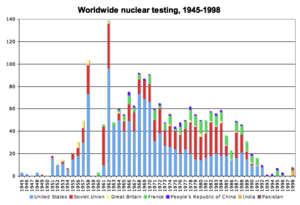

Scientists and leaders started talking about nuclear weapons even before the first atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. People became worried about nuclear weapons testing around 1954, especially after many tests in the Pacific Ocean. In 1961, during the Cold War, about 50,000 women from a group called Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities across the United States to protest nuclear weapons. In 1963, many countries signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty, which stopped nuclear tests in the atmosphere.

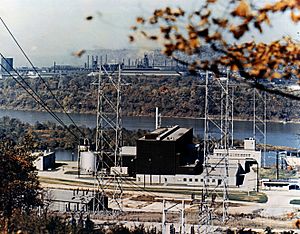

Some people also started to oppose nuclear power plants in the early 1960s. By the late 1960s, some scientists also shared their concerns. In the early 1970s, large protests happened in Wyhl, Germany, against a planned nuclear power plant. The project was stopped in 1975. This success in Wyhl encouraged more opposition to nuclear power in Europe and North America. Nuclear power became a major issue for public protests in the 1970s.

The Start of the Movement (1940s-1960s)

In 1945, American scientists carried out "Trinity" in the New Mexico desert. This was the very first nuclear weapons test, marking the beginning of the "atomic age." Even before this test, leaders discussed how nuclear weapons would affect their countries and the world. Scientists also joined this debate through groups like the Federation of Atomic Scientists.

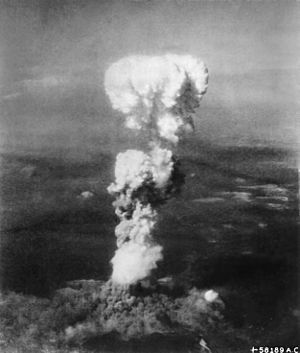

Towards the end of World War II, on August 6, 1945, the "Little Boy" atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. It exploded with the power of 12,500 tons of TNT. The blast destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings and killed about 75,000 people. Three days later, the "Fat Man" bomb exploded over Nagasaki, destroying 60% of the city and killing about 35,000 people. These two bombings are the only times nuclear weapons have been used in combat. After this, the world's supply of nuclear weapons grew.

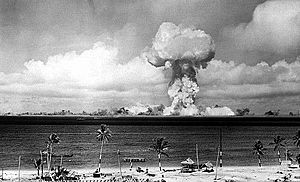

Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests by the United States in 1946. These tests happened at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. Their goal was to see how nuclear weapons would affect naval ships. Scientists and diplomats tried to stop Operation Crossroads. They argued that more nuclear testing was not needed and was dangerous for the environment. A study warned that the water near an explosion would be "a witch's brew" of radioactivity. To prepare for the tests, the people living on Bikini Atoll were forced to leave their homes. They were moved to smaller islands where it was hard for them to live.

People first became aware of radioactive fallout from nuclear tests in 1954. This happened when a Hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated a Japanese fishing boat called the Lucky Dragon. One of the fishermen died seven months later. This event caused great concern worldwide. It strongly encouraged the start of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries. For many, the atomic bomb showed the worst direction society could go.

Peace groups formed in Japan. In 1954, they joined together to create the "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs." Many Japanese people opposed the Pacific nuclear weapons tests. About 35 million signatures were collected on petitions asking for bans on nuclear weapons.

In Germany, publications in the 1950s and 1960s criticized some parts of nuclear power, including its safety. Getting rid of nuclear waste was seen as a big problem. Concerns were publicly shared as early as 1954.

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was released in London on July 9, 1955, during the Cold War. It warned about the dangers of nuclear weapons. It also asked world leaders to find peaceful ways to solve international problems. Eleven important thinkers and scientists signed it, including Albert Einstein, who signed it just days before he died. This led to the first Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs in July 1957.

In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March took place in 1958. It was organized by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Thousands of people marched for four days from London to the Atomic Weapons Establishment to protest nuclear weapons. These marches continued into the late 1960s, with tens of thousands of people joining.

In 1959, a letter in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists started a successful effort. It stopped the Atomic Energy Commission from dumping radioactive waste into the sea near Boston.

On November 1, 1961, during the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women marched in 60 cities in the United States. They were brought together by Women Strike for Peace to protest nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women's peace protest of the 20th century.

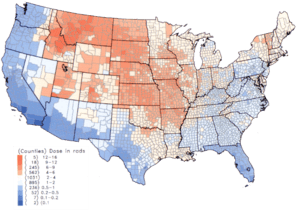

In 1958, Linus Pauling and his wife gave the United Nations a petition. More than 11,000 scientists had signed it, asking for an end to nuclear-weapon testing. The "Baby Tooth Survey" in 1961 showed that above-ground nuclear testing was a big health risk. It spread radioactive fallout mainly through milk from cows that ate contaminated grass. Public pressure and this research led to a pause in above-ground nuclear weapons testing. This was followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. On the day the treaty began, Linus Pauling received the Nobel Peace Prize. He was honored for his tireless work against nuclear weapons and all warfare.

After the Test Ban Treaty (1960s-1980s)

In the United States, the first commercial nuclear power plant was planned for Bodega Bay, California. But the idea was very controversial. Local citizens started protesting in 1958. The proposed site was near the San Andreas Fault and important fishing and dairy areas. The Sierra Club group also got involved. The protests ended in 1964, and the plans for the power plant were stopped. Many see this as the beginning of the anti-nuclear movement. Similar protests also stopped plans for a nuclear plant in Malibu.

In 1966, Larry Bogart started the Citizens Energy Council. This group published newsletters that argued nuclear power plants were too complex, expensive, and unsafe. They believed these plants would cause financial problems and health dangers.

The anti-nuclear power movement grew as people became more aware of environmental issues in the 1960s. Some nuclear experts started to disagree with nuclear power in 1969. This was important for wider public concern to grow. Scientists like Ernest Sternglass, Henry Way Kendall, George Wald, and Rosalie Bertell spoke out. They helped ordinary citizens understand the issues. Nuclear power then became a major public protest issue in the 1970s.

In 1971, 15,000 people protested against plans for a nuclear power plant in Bugey, France. This was the first of many large protests at almost every planned nuclear site in France.

Also in 1971, the town of Wyhl, Germany, was chosen for a nuclear power station. Over the next few years, public opposition grew, and there were large protests. TV showed police dragging away farmers, which made nuclear power a big issue. In 1975, a court stopped the construction license for the plant. The Wyhl protests encouraged other citizen groups to form near planned nuclear sites. Many other anti-nuclear groups formed to support these local fights. The success in Wyhl also inspired nuclear opposition in the rest of Europe and North America.

In 1972, the anti-nuclear weapons movement stayed active in the Pacific. This was mainly because of French nuclear testing there. Activists, including David McTaggart from Greenpeace, sailed small boats into the test zone to stop the testing program. In Australia, thousands joined protest marches in several cities. Scientists demanded an end to the tests. Unions refused to handle French ships or mail, and people stopped buying French products. In Fiji, activists formed a group called "Against Testing on Mururoa."

In Spain, a strong anti-nuclear movement started in 1973. This was in response to many new nuclear power plant proposals in the 1960s. This movement eventually stopped most of those projects.

In 1974, farmer Sam Lovejoy used a crowbar to damage a weather tower at the Montague Nuclear Power Plant site. Lovejoy then went to the police station and took responsibility. His action brought local public opinion against the plant. The Montague project was canceled in 1980, after $29 million had been spent on it.

By the mid-1970s, anti-nuclear activism had grown beyond local protests. It gained wider support and influence. Even though it didn't have one main group guiding it, the movement got a lot of attention. Jim Falk suggested that public opposition to nuclear power quickly grew into a strong anti-nuclear power movement in the 1970s. In some countries, the nuclear power conflict became more intense than any other technology debate in history.

In France, between 1975 and 1977, about 175,000 people protested against nuclear power in ten different demonstrations.

In West Germany, between February 1975 and April 1979, about 280,000 people took part in seven demonstrations at nuclear sites. Some groups also tried to occupy sites. After the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, about 120,000 people protested nuclear power in Bonn.

In May 1979, an estimated 70,000 people, including the governor of California, marched and rallied against nuclear power in Washington, D.C.

On June 12, 1982, one million people protested in New York City's Central Park. They were against nuclear weapons and wanted an end to the cold war arms race. This was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest peace demonstration in American history. International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests happened on June 20, 1983, at 50 locations across the United States. In 1986, hundreds of people walked from Los Angeles to Washington DC in the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament. Many protests and peace camps also took place at the Nevada Test Site during the 1980s and 1990s.

On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear and anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York. This was 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. in decades. In Britain, many protested the government's plan to replace the old Trident weapons system. The biggest protest had 100,000 people, and polls showed 59 percent of the public were against the plan.

The International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament happened in Oslo in February 2008. It was organized to help nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states agree on the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty. The goal was to work towards a world free of nuclear weapons.

In May 2010, about 25,000 people, including peace groups and survivors of the 1945 atomic bombings, marched in New York. They walked to the United Nations headquarters, calling for the removal of all nuclear weapons.

See also

- The Bomb (film)

- Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Nuclear power debate

- Nuclear weapons debate

- Uranium mining debate

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |