History of the lumber industry in the United States facts for kids

The history of the lumber industry in the United States tells the story of how people have used trees in America, from early times to today. Long ago, England ran out of most of its own trees. So, they looked to the "New World" (America) where there were huge, old forests. These forests were an amazing resource for early settlers. They used wood for building and also sold it to other countries.

The lumber business grew very fast as Americans moved across the country. Sadly, this expansion often meant that indigenous peoples lost their lands and traditional ways of life. By the 1790s, places like New England were sending out huge amounts of pine boards and ship masts every year. By 1830, Bangor, Maine became the biggest port for shipping lumber in the world. It moved billions of feet of timber over the next 60 years.

Contents

Colonial Times and Early Forests

By the 1200s, most of England's forests were gone. More trees were cut down in the 1540s to fuel England's growing iron industry. To save their remaining trees, a law was passed in 1543. It limited how close trees could be cut to private land. But by the 1600s, even the king's own forests were used up. This made the price of firewood double, and many poor people suffered.

In 1584, Richard Hakluyt, a famous geographer, wrote about colonizing North America. He believed it would provide jobs and natural resources for England. Trees were one of the main resources he mentioned. Hakluyt thought America's endless supply of wood would solve England's timber problems. He felt that a strong lumber industry would make settling America worthwhile.

Hakluyt and seven other men started the Virginia Company. On April 10, 1606, King James I gave them a special paper called the First Charter of Virginia. This paper allowed them to start a colony in America. The company split into two groups: the London Company and the Plymouth Company.

On December 20, 1606, 100 men and four boys sailed from England. They arrived in Chesapeake Bay on April 10, 1607. On April 26, 1607, the London Company settled in Virginia. They named their new home Jamestown after the King.

Early Wood Exports and Rules

The London Company quickly started sending trees back to England. One letter from 1608 mentioned "sweet woode" being sent. However, large-scale exports were delayed. In the winter of 1609, many colonists died during a tough time called the Starving Time. It took another 11 years for serious timber production to begin in New England.

In 1621, the Plymouth Company sent a ship called the Fortune back to England. It was "laden with good clapboard," which is a type of wood siding. Soon, the pilgrims realized their wood was too valuable to export. They made a rule that no one could sell or transport wood that would "destroy timber" without the governor's permission. By the 1680s, over two dozen sawmills were working in southern Maine.

Building Early Homes

Settlers needed homes to create permanent communities. In Jamestown, the London Company quickly built a fort for protection. By mid-June 1607, the fort was finished. It was shaped like a triangle and held a church, a storehouse, and living quarters. By 1614, Jamestown had "two faire rowes of howses," made of timber, two stories high.

Before Europeans arrived, Patuxet Indians had been shaping the forests for thousands of years. They would burn and clear parts of the forest to grow corn and build their homes. Many early colonial towns, like Plymouth and Boston, were built on these cleared areas. But by the mid-1630s, these areas became too crowded. New settlers had to move into the woods to claim land.

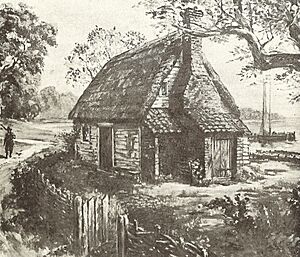

One colonist described building a simple shelter. They would dig a pit, line it with wood and bark, and then build a roof of spars covered with bark and grass. As more tools and supplies arrived, home building improved. People built sturdy wood-frame houses with clapboard exteriors. By 1612, they were even making bricks for chimneys and homes for wealthier people.

Typical homes in the 1600s were one-story buildings. They often had a loft reached by a ladder. There were usually chimneys at both ends where meals were cooked over an open fire. These houses were about 30 to 40 feet long and 18 to 20 feet wide.

Trading Wood Products

In the 1600s, there was almost no trade of wood between England and New England. It took nearly 50 years for England to send ships to get masts and ask colonists to produce timber. However, wood was used for many everyday items. Hickory, ash, and hornbeam were used for bowls and tools. Cedar and black walnut were used for decorative boxes and furniture. Maple sap was even used as a sweetener.

England's Navigation Acts usually stopped New England from trading with other European countries. But timber was an exception. This allowed the colonies to sell large amounts of wood to Spain, Portugal, and other places. They traded oak staves for wine barrels, building timber, pine boards, and cedar shingles. Trade between the colonies was also allowed. This led to a big trade relationship with Barbados.

Barbados and other Caribbean islands had cut down all their own trees to grow sugar. They became very dependent on timber from New England. By 1652, New England had strong overseas markets. They shipped lumber, ships, and fishing goods.

Building Ships for Trade

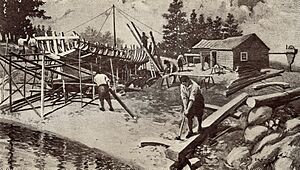

On April 27, 1607, the London Company colonists built a small boat. In the 1600s, most trade happened by water. The "shallop" was a popular boat in Virginia. It was small (16-20 feet long) and perfect for exploring rivers, trading, and moving tobacco.

At first, shipbuilding in Virginia was simple. Plantation owners built boats near streams with deep water. They needed access to good timber. But boatbuilding didn't grow much at first. Many early boat builders died in the Indian massacre of 1622.

By 1629, the companies funding the colonies were worried about not making money. So, the New England Company and the Massachusetts Company sent their own shipbuilders. Suddenly, shipbuilding boomed in Boston and Charlestown in the early 1630s. The area was perfect for it.

White oak was excellent for ship timber and planks. Cedar, chestnut, and black oak were great for the underwater parts of ships. These woods were strong, durable, and didn't let water in. Within ten years, many boats and ships were being built.

In 1662, the General Assembly of Virginia offered rewards to encourage shipbuilding. For example, if someone built a ship over 100 tons, they would get 200 pounds of tobacco per ton. Builders also got tax breaks on exports and imports. This helped shipbuilding grow even more.

Ships in Virginia became larger and better made. By 1666, people in England were amazed at how quickly New England's shipbuilding had improved. They thought Americans would soon build ships as good as England's. By 1690, ships of 300 tons were being built in Virginia.

The King's Broad Arrow

Even with more timber production, wood wasn't as profitable as Hakluyt had hoped. This was partly because workers in America were paid more than in Europe. Also, shipping costs across the ocean were high. Shipping from Boston cost much more than from Baltic ports.

Things changed when England faced a timber crisis. The Navigation Acts of 1651 limited imports to England. Denmark started attacking British ships carrying timber from the Baltic Sea. Just before the first Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654), England's navy, the Admiralty, decided to get timber and masts from North America. They needed a reliable source for repairing battle-damaged masts.

North American white pine became the Admiralty's second choice for masts. It was lighter and much larger than European fir. White pines could reach 250 feet tall and weigh 15 to 20 tons. So, in 1652, the Admiralty sent ships to New England to get masts. This started England's steady import of New England masts.

New England's shipbuilding industry grew quickly. It became common for the British to buy ships from New England because they were 30% cheaper to build. This made shipbuilding the most profitable export during the colonial period.

The Admiralty's need for mast logs also helped create a workforce. This led to a booming local lumber industry. Most New England pines were not suitable for masts. These "rejected" trees were then used to make boards, joists, and other building lumber. The Crown worried that this new resource would quickly run out.

In response, King William III created a new rule in October 1691 for the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It said that all trees 24 inches or wider belonged to the King, unless they were already owned by someone. This rule became known as the King's Broad Arrow. Trees marked with three ax strikes (like an upside-down arrow) were reserved for the King.

This policy became even more important during the Great Northern War (1700–1721). This war almost stopped timber exports from the Baltic to England. So, the British Parliament passed laws to encourage imports from New England.

For example, the Act of 1704 offered money for importing naval supplies from New England. The Act of 1705 made it illegal to cut small pine trees. The Act of 1711 gave the Survey General of the King's Forests power over all colonies from New Jersey to Maine. The Act of 1721 extended this power to any trees not in a town. It also officially recognized the American word 'lumber'.

However, these laws were very hard to enforce. A survey in 1700 found over 15,000 logs that broke the 24-inch rule. Colonists often ignored the Broad Arrow mark. It was almost impossible for one surveyor and a few helpers to police all of New England's forests. The policy's effect on the American economy is still debated. It did ensure England had a steady supply of mast timber. But colonists saw it as a violation of their property rights, which helped fuel the desire for rebellion. New England timber continued to be shipped until the American Revolutionary War. The last supply of masts reached England on July 31, 1775. By then, over 4,500 white pines had been sent under the Broad Arrow policy.

Lumber's Role in the New United States

The Industrial Revolution in America greatly increased the need for timber. Before the American Civil War, over 90% of the nation's energy came from wood. Wood powered trains and steamboats. As Americans settled the treeless Great Plains, they needed lumber from other parts of the country to build their towns. The growing railroad industry used a quarter of all lumber. It needed wood for rail cars, stations, ties, and to fuel trains. Even when coal started replacing wood as an energy source, the coal mining industry still needed lumber for mine supports and rail beds.

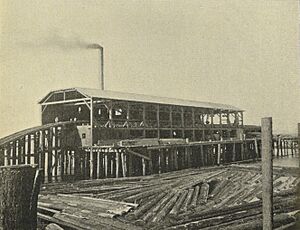

New technology helped the industry meet this huge demand. Steam engines made it possible to log further inland, away from rivers. New machines like the circular saw and band saw cut trees much faster. This increased timber production quickly used up New England's forests. American loggers then moved south and west to find new forests.

The 1800s: Moving West

| United States Lumber Production |

|

|---|---|

| Year | Annual Production (millions of board feet) |

| 1850 | 5,000 |

| 1860 | 8,000 |

| 1870 | 13,000 |

| 1880 | 18,000 |

| 1890 | 23,500 |

| 1900 | 35,000 |

By the 1790s, New England was exporting 36 million feet of pine boards and 300 ship masts each year. Most of this came from Massachusetts (which included Maine) and New Hampshire. By 1830, Bangor, Maine became the world's largest port for shipping lumber. It moved over 8.7 billion board feet of timber in 60 years.

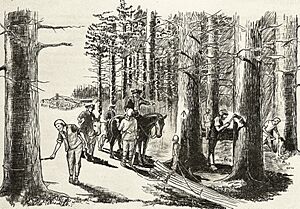

Throughout the 1800s, Americans moved west looking for new land and resources. The timber supply in the Midwest was shrinking. This forced loggers to find new sources of "green gold." In the early 1800s, the Great Lakes region had huge forests of old-growth timber. This wood became a main resource for building materials, industry, and fuel across the country.

By 1840, upstate New York and Pennsylvania were the center of the lumber industry. By 1880, the Great Lakes region, especially Michigan, produced more lumber than any other state.

Forests Disappearing: 1780s to 1860s

By 1860, about 153 million acres of forest had been cleared for farms. Another 11 million acres were cut down for logging, mining, railroads, and cities. A quarter of the original forests in the eastern states were gone. At the same time, Americans started to see forests differently. They realized forests were key to industry, farming, and progress.

Lumber was the biggest industry in the nation in 1850. It was second only to textiles in 1860. Forests were important for "cheap bread, cheap houses, cheap fuel, and cheap transportation." Wood was the main fuel for homes, businesses, steamboats, and railroads. Experts began to study how forests related to soil, climate, farming, and the economy. They wondered about the overall balance of nature. Was the nation's energy at risk as people moved west into the prairies where wood was scarce?

Some people, like George Perkins Marsh and Increase Lapham, worried about the widespread destruction. They saw forests as symbols of America. Their disappearance was concerning. Writers like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson helped people appreciate forests for their beauty and recreation, not just their economic value. These concerns were the start of the early conservation movement.

The 1900s: Moving West Again

By 1900, timber in the upper Midwest was running low. American loggers looked further west to the Pacific Northwest. The shift was very sudden. In 1899, Idaho produced 65 million board feet of lumber. By 1910, it produced 745 million. By 1920, the Pacific Northwest produced 30% of the nation's lumber.

Before, individuals or families ran single sawmills. They sold lumber to wholesalers. But by the late 1800s, large industrialists started to take over. They owned many mills and bought their own timberlands. No one was bigger than Frederick Weyerhauser and his company. He started in 1860 in Rock Island, Illinois. His company expanded to Washington and Oregon. By the time he died in 1914, his company owned over 2 million acres of pine forest.

The Great Depression's Impact

When the Great Depression started, many companies had to close. Total lumber production fell sharply. It went from 35 billion board feet in 1920 to only 10 billion board feet in 1932. Also, incomes dropped, profits fell, and people started using more cement and steel instead of wood. This made the decline in lumber production even worse.

| United States Gross Income, Net Profits, Production, and price index in the Lumber Industry 1920 -1934 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Gross Income (In Millions Dollar) |

Net Profit (In Millions Dollar) |

Production (In Board feet) (In Millions) |

Wholesale Price Index (1926=100) |

| 1920 | 3,312 | N/A | 35,000 | N/A |

| 1922 | 2,402 | 167 | 35,250 | N/A |

| 1924 | 2,835 | 132 | 39,500 | 99.3 |

| 1926 | 3,069 | 117 | 39,750 | 100.0 |

| 1928 | 2,342 | 82 | 36,750 | 90.5 |

| 1930 | 1,988 | 110 | 26,100 | 85.8 |

| 1932 | 854 | 202 | 10,100 | 58.5 |

| 1934 | N/A | N/A | 12,827 | 84.5 |

In 1933, after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was passed. President Roosevelt believed that too much competition was a cause of the Great Depression. National lumber codes were created to control things like wages, hours, and prices in the industry.

The industry was struggling with low prices, low wages, and forests that were used up from too much cutting in the late 1920s. As the table shows, prices went up in 1934. This was due to the lumber codes, but also other factors like changes in money value, more public spending, and a better banking system.

As old-growth forests quickly disappeared, America's timber resources no longer seemed endless. A Canadian lumberman named James Little said in 1876 that the rate of logging in the Great Lakes was like "burning the candle at both ends."

To deal with less available timber, the Division of Forestry was created in 1885. In 1891, the Forest Reserve Act passed. It set aside large areas of forest as federal land. Loggers had to make already cut lands productive again. Reforesting timberlands became a key part of the industry. Some loggers moved further northwest to Alaskan forests. But by the 1960s, most of the remaining uncut forests became available for logging.

New tools like the portable chain saw made logging more efficient. But in the 1900s, other building materials became popular. This meant the demand for lumber didn't keep rising as fast as before. In 1950, the U.S. produced 38 billion board feet of lumber. This number stayed about the same for decades. In 1960, it was 32.9 billion, and in 1970, it was 34.7 billion.

The 2000s: Modern Lumber Industry

Today, the United States has a strong lumber economy. It directly employs about 500,000 people in three main areas: Logging, Sawmills, and Panel production. The U.S. produces over 30 billion board feet of lumber each year. This makes it the largest producer and consumer of lumber in the world. Even with new technology and safety efforts, the lumber industry is still one of the most dangerous jobs.

The United States is the second largest exporter of wood in the world. Its main customers are Japan, Mexico, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Because labor costs are higher in the U.S., raw wood is often sent to other countries. There, it's made into finished products and then sent back to the United States. So, the U.S. exports more raw wood (like logs and wood chips) than it imports. But it imports more finished wood products (like lumber, plywood, and veneer) than it exports.

Recently, there has been a comeback for logging towns in the U.S. This is largely because of the recovery in the housing market. During the COVID-19 pandemic's building boom, lumber prices reached all-time highs.

See also

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |