History of the oil shale industry in the United States facts for kids

The history of the oil shale industry in the United States is quite old, even older than the regular oil industry! The U.S. has the world's largest known supply of oil shale, but it hasn't produced much oil from it since 1861. There have been three main times when people tried to start a big oil shale industry in America: in the 1850s, around World War I, and in the 1970s and early 1980s. Each time, the oil shale industry struggled because regular petroleum (crude oil) was cheaper.

As of 2014, some companies are still researching oil shale in Colorado and Utah. However, no oil is being produced from shale on a large scale in the United States right now.

Contents

America's Huge Oil Shale Supplies

The United States hasn't had a successful oil shale industry for over 150 years. Yet, it holds the biggest oil shale resource in the entire world!

Oil Shale in the East

East of the Mississippi River, there are two kinds of oil shale. The first is called cannel coal. This was widely used in states like Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia to make oil between 1854 and 1861. Most of this cannel coal has now been mined out.

The second type of eastern oil shale is called Paleozoic black shales. These don't produce as much oil but are found in much larger amounts. People have paid the most attention to shales from the Devonian and Mississippian periods. These are known by names like Ohio Shale or Chattanooga Shale.

Oil Shale in the West

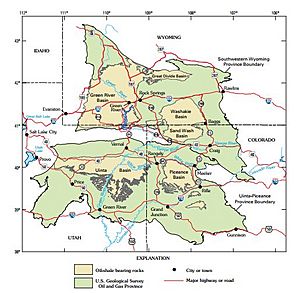

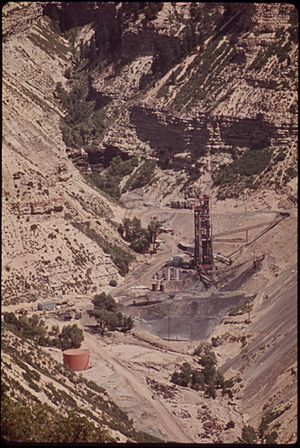

Similar black shales are found across the western United States. However, the biggest oil shale resource in the world is located in the Eocene Green River Formation. This is in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. Most efforts to create an American oil shale industry have focused on these Green River oil shales.

The Green River oil “shale” is actually a type of rock called marl. Some parts of it can produce up to 70 gallons of oil from just one short ton of rock! Experts believe there's enough oil in the ground to make 4.2 trillion barrels of oil. The Piceance Basin in western Colorado has the richest shale. It could hold about 352 billion barrels of oil.

Other oil shale deposits exist, like the Elko Formation in Nevada. This formation also formed in a lake. Another is the Phosphoria Formation in Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana. Some parts of it can yield over 25 gallons of oil per ton.

The 1850s: The Coal Oil Era Begins

In the mid-1800s, America had a problem: a shortage of whale oil. Even with more and more whaling ships, the demand for lamp oil was too high. The price of whale oil went way up, and the country had to import more of it.

Whale oil was important for lamps because it burned brightly without much smoke. Other oils from coal or turpentine burned with smoky flames, which wasn't good for indoor lighting. A mixture of turpentine and alcohol called "burning oil" was bright but could explode. Because of this, fire insurance cost more for buildings using it.

The high demand for whale oil led to a big drop in whale populations. Scientists tried to create a cheap, artificial oil that would burn well and be safer. Two people succeeded: Scottish chemist James Young and Canadian geologist Abraham Gesner. They both made lamp oil by heating coal or similar materials. Young found that a type of coal called cannel coal produced the most oil.

By 1853, Abraham Gesner learned to make good lamp oil from a rock called "albertite" in Canada. He moved to New York City and started a company. In 1854, Gesner received a patent for his process to make a lamp oil he named Kerosene. Kerosene quickly became his company's main product.

The Coal Oil "Mania" Takes Off

The success of Young and Gesner inspired many others. The Scientific American magazine noted that the number of American companies making coal oil jumped from three in 1857 to over 42 by 1859. The magazine called this rush a "mania."

A whale-oil dealer named Samuel Downer Jr. bought a struggling company in Massachusetts. After a chemist visited Scotland, the company focused on making lamp oil from imported albertite. By late 1858, Downer Company was a leader in the coal oil business.

The first American company to use local coal was the Breckinridge Cannel Coal Company in Kentucky. In 1856, their new equipment started producing 600 to 700 gallons of lamp oil daily. They had the advantage of being near large cannel coal deposits and the Ohio River for cheap shipping. Other companies began extracting oil from Devonian oil shale along the Ohio River in 1857.

Oil shale companies set up their factories in two ways: either close to their customers or close to the oil shale.

- Some built factories near big cities on the East Coast. They would ship coal or shale long distances, often from Canada or Scotland. New York had at least fourteen such companies, and Boston had seven.

- Others built factories close to the oil shale itself. Then, they would ship only the finished oil long distances. This was common in the Ohio River Valley. At least 25 companies set up factories along the Ohio River. Major centers included Pittsburg, Cincinnati, and Kanawha (now in West Virginia).

By early 1860, there were between 60 and 75 oil shale companies in the U.S. They produced seven to nine million gallons of lamp and lubricating oil each year. Lamp oil from shale had improved greatly. It was praised for giving "more and cheaper light than any other substance." It was replacing turpentine-based lamp oils and expensive whale oil.

Cheap Petroleum Ends the Coal Oil Industry

Today, oil shale is seen as "unconventional," and drilling for crude oil is normal. But in the late 1850s, it was the other way around. The oil shale industry was strong when Edwin Drake drilled for oil in Pennsylvania in 1859. Drilling for crude oil was the new, unproven idea.

Small-scale petroleum refining had been happening since 1851. Samuel Kier, a salt maker in Pittsburgh, started distilling petroleum that was getting into his salt wells. He sold this as lamp oil to miners.

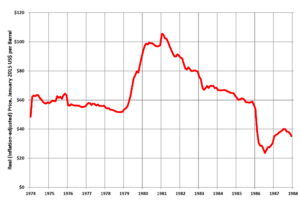

On August 28, 1859, Edwin Drake found oil in a 70-foot deep well in Pennsylvania. This discovery started a huge rush to drill for oil. This boom spread across the Ohio Valley, the same area where many oil shale factories were located. In 1861, so much petroleum flooded the market that its price dropped to just 52 cents per barrel. Lamp oil makers quickly switched to petroleum because it was much cheaper. Also, refining petroleum wasn't patented, so companies didn't have to pay fees. The existing oil shale refineries had to change to use petroleum instead. The American oil shale industry, which was booming just a year before, suddenly stopped. Cheap petroleum had put oil shale out of business.

World War I and the Need for Gasoline

World War I put a lot of pressure on oil supplies. Even after the war, people bought more and more cars, so the demand for gasoline kept rising fast. Even though the U.S. was producing more oil, it couldn't keep up. The country had to import more oil, which made prices go up. Many experts worried that the world would soon run out of petroleum.

Some experts believed that the U.S. would reach its highest oil production by 1921 and then decline. Others thought that the world's oil supply from wells would be mostly gone within a middle-aged person's lifetime.

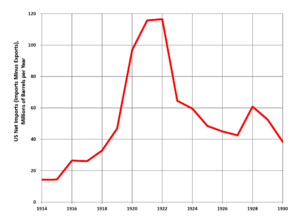

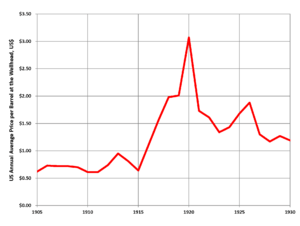

The average price of crude oil in the U.S. more than tripled, from $0.64 per barrel in 1915 to $2.01 in 1920. U.S. oil production grew, but it couldn't match the demand. Net imports of crude oil to the U.S. jumped from 18 million barrels in 1915 to 106 million barrels in 1920.

The largest oil shale resource, the Green River Formation, was found by accident in 1874. People knew that these rocks could produce oil when heated. But a 1914 government report made everyone aware of just how huge this resource was.

In 1912, President Taft created the first Naval Oil Reserves. These were large federal lands with oil deposits, meant to be used only if the Navy couldn't buy oil elsewhere. Because oil shale was expected to be so important, President Woodrow Wilson created two Naval Oil Shale Reserves in 1916. These were large areas of prime oil shale land kept from private ownership.

The First Western Oil Shale Boom

Rising oil prices and the idea of a permanent oil shortage attracted many people to the oil shale areas of Colorado and Utah. About 100 new companies formed to mine and process oil shale. Many of them also sold company shares.

Many of these new companies were real, but they had to compete with dishonest promoters. These promoters made exaggerated promises. For example, some claimed they could get gasoline directly from heating the shale. One even promised to extract gold from oil shale! The U.S. Bureau of Mines had to tell the public that no gold could be found in oil shale.

In 1915, people could claim mineral rights to oil shale land under an old mining law. But in 1920, Congress passed a new law. It said that rights to oil and oil shale had to be leased from the federal government instead.

By September 1920, none of the many oil shale companies were producing oil on a large scale. Only a few were close. One plant in Denver claimed it could recover gold and platinum from shale, along with oil.

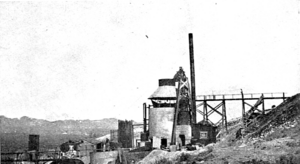

Mining engineer Robert Catlin made the first attempt to produce oil from western deposits. In 1890, he bought land near Elko, Nevada, that had oil shale. When oil prices rose in 1915, he built equipment and started producing oil. He refined it into gasoline and lubricating oil, but the quality was said to be low. His company produced about 12,000 barrels of oil from shale before closing in 1924. Of the many companies that formed during this boom, Catlin's was one of the few that actually produced and sold oil on a commercial scale.

Other companies like Cities Service, Standard Oil of California, and Texaco also started oil shale operations between 1918 and 1920. About 200 companies were created to work with oil shale, and at least 25 different ways of heating the shale were tested.

While most attention was on the Green River Formation in the west, some companies also tried to develop the eastern shales. Even though eastern shales produced less oil, they had better roads and water supplies, and were closer to markets.

Cheap Petroleum Ends the Shale Oil Business Again

The high price of petroleum encouraged more oil exploration. This led to the discovery of large new oil fields in the U.S. and elsewhere. American oil production surged in the early 1920s, especially in Texas and California. This caused both oil imports and oil prices to drop. The price of a barrel of oil in the Midcontinent region fell by almost two-thirds in 1921.

The drop in oil prices and the new oil discoveries calmed fears about the U.S. running out of oil. Oil shale simply couldn't compete when petroleum was cheap, especially since the best shale areas were far from major markets. Cheap petroleum prices once again put the oil shale industry out of business.

Between the Booms: Research Continues

Even after the busts, some companies kept working on better ways to process oil shale. One important invention before World War II was the N-T-U retort. The U.S. Bureau of Mines also tested this technology.

During World War II, concerns about oil supplies led Congress to create the Synthetic Liquid Fuels Program in 1944. This program aimed to create liquid fuel from domestic oil shale. The Bureau of Mines built a test facility in Colorado to try out different ways of mining and heating the Green River oil shales.

In 1951, the United States Department of Defense became interested in oil shale for making jet fuel. The Bureau of Mines continued its research until 1956. They even opened a small demonstration mine.

In the 1960s, a plan called Project Bronco suggested using a nuclear explosive to break up rock underground for oil extraction. This plan was later dropped. Other companies also worked on in-situ (meaning "in place" or underground) processing methods.

By the 1940s, big oil companies like Chevron and Texaco owned large oil shale areas. Unlike the 1920s boom, which had many small, new companies, the research after World War II was a serious, long-term effort by established oil companies.

Union Oil Company of California built and tested its own process in Colorado in 1957 and 1958. This production stopped in 1961 because it was too expensive. In the early 1960s, TOSCO (The Oil Shale Corporation) opened an underground mine and built a test plant. It closed in 1972 because the cost of producing oil from shale was higher than the cost of imported crude oil.

The 1970s: The Energy Crisis

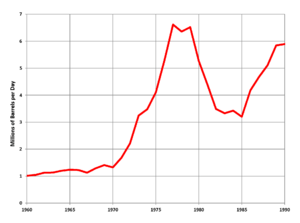

America faced another oil shortage. Several things combined to create the 1970s energy crisis. U.S. crude oil production started to decline after 1970, so the country had to import more oil. Natural gas production also dropped. A strong world economy meant that oil sellers had more power than buyers. OPEC, a group of oil-producing countries, used this to demand higher prices. In 1973, some Arab countries stopped shipping oil to nations supporting Israel, including the United States. These sudden changes in oil price and supply caused problems. Gasoline stations ran out of fuel, and drivers waited in long lines to fill their tanks.

Many experts again said that America was quickly running out of oil. Geologist King Hubbert had correctly predicted the peak of U.S. oil production. A famous 1972 report called Limits to Growth also predicted that the world would soon face shortages of natural resources.

The U.S. government responded with many plans. One was to encourage oil shale production by leasing large areas of federal land in Colorado and Utah.

The New Oil Shale Boom

The U.S. Navy started looking into oil shale for military fuels like jet fuel. Shale-oil based jet fuel was produced until the early 1990s. In 1974, the United States Department of the Interior announced a program to lease federal land for oil shale. The Synthetic Fuels Corporation was also created in 1980 to help.

In 1972, Occidental Petroleum did the first in-situ oil shale experiment in the U.S. This meant they tried to get the oil out while the shale was still underground. Other companies like Rio Blanco Oil Shale Company and White River Shale Corporation also worked on similar projects.

In 1977, Superior Oil Company canceled its oil shale plant project. Later, Ashland, Cleveland Cliffs Company, and Sohio left the Colony Shale Oil Project near Parachute, Colorado. Shell also left the Colony project but continued its in-situ tests.

In 1970, the Bureau of Mines estimated that shale oil would cost $2.71 per barrel to produce, not including profit or taxes.

TOSCO (The Oil Shale Corporation) developed its own method for heating shale. In 1963, it formed the Colony Development Co. to build a test plant. This company was a group of TOSCO, Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Co., and Standard Oil of Ohio (SOHIO). Construction on the Colony plant began in 1965.

Another group of 17 energy companies, including Chevron and Texaco, formed the Paraho Development Corporation in 1973. They used their own special technology to get over 90 percent of the oil out of the shale. The company produced over 100,000 barrels of shale oil in the late 1970s.

Sunoco and Phillips Petroleum teamed up to win a lease on federal land in Utah for $76 million. They formed the White River Shale Oil Corporation. They planned to produce 100,000 barrels of shale oil per day. However, their leases were put on hold for several years due to environmental and land issues.

Gulf Oil and Chevron Corporation formed the Rio Blanco Oil Shale Company in 1974. They won a lease on federal land for $210.3 million. Rio Blanco planned to mine oil shale from an open pit. Later, they switched to in-situ mining. They recovered about 25,000 barrels of oil before groundwater stopped their underground operations in 1984.

In 1976, a group including TOSCO, Shell Oil, and Atlantic Richfield Company leased federal land in Colorado. They planned to mine the oil shale underground. ARCO and TOSCO later left the project. Occidental Petroleum Corporation had been successfully producing shale oil using in-situ methods at its test site. They decided to use this method for the larger project. They planned to break the oil shale underground with explosives and then produce oil by controlled burning. This oil would then be pumped to the surface.

Chevron and Conoco started the Clear Creek Project in 1981. They planned to mine oil shale underground and process it on the surface.

Large oil companies saw their potential oil reserves grow hugely by getting into oil shale. Union Oil's shale property, for example, promised to increase its oil production by 50% for 40 years. But as projects grew, companies found they were betting billions of dollars on oil shale. Some looked for partners to share the risk, and some sold out completely.

The Colony Oil Shale Project changed owners many times. Eventually, only TOSCO (with 40%) and Exxon owned it. They planned a $5 billion project to mine and process oil shale.

Black Sunday: The End of the American Shale Oil Industry (1982-1991)

Once again, oil shale was defeated by lower petroleum prices. Oil prices started to fall in 1981. Starting in late 1981, one by one, the oil shale companies gave up their billion-dollar projects. They took their losses and stopped trying to produce oil commercially.

In December 1981, Occidental Petroleum and Tenneco announced they were stopping work on the Cathedral Bluffs project. They laid off hundreds of employees. They blamed rising construction costs and falling oil prices. Even with government help, the project struggled. Pumping and maintenance stopped in 1991, and the main building was torn down in 2002. The project never produced any oil.

The date often called the end of the oil shale boom is Sunday, May 2, 1982. This day is known as "Black Sunday." Exxon announced it was closing its Colony Oil Shale Project and laying off over 2,200 workers. The project had cost its owners over $1 billion by the time they quit. No commercial shale oil was ever produced.

All the nearby towns suffered economically. The community of Battlement Mesa, built to house the Colony project employees, became a ghost town overnight. But the town was saved when its properties were sold as retirement homes. Enough retirees bought homes at bargain prices to turn the town around in just a few years.

Of all the attempts to start large-scale oil shale operations, only the Union Oil project continued. Union Oil spent $1.2 billion and shipped its first barrel of oil in 1986. The plant produced 5,000 to 7,000 barrels per day at its peak, with some government help. In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed a law that ended the U.S. Synthetic Liquid Fuels Program. Union finally gave in to continued low oil prices and closed the project in 1991.

Over several decades, some of the world's largest oil companies spent billions of dollars trying to start an oil shale industry in the Green River Formation. This is the world's largest oil shale resource. But in the end, cheap petroleum prices drove oil shale out of business.

Oil Shale in the 21st Century

Even after the oil shale bust, some companies kept going. Shell Oil continued testing in-situ methods. In 1997, it started a field test of its Shell in situ conversion process. In 2016, Shell successfully tested its process in Jordan and later created a new company called Salamander Solutions for this technology.

A new oil shale development program started in 2003. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 told the Department of Energy and the Department of the Interior to start leasing federal land for oil shale production. The government planned a step-by-step approach. Companies would first do research and development on a small area. Then, they could expand to a larger area for commercial production.

In 2005, the government asked for companies to apply to lease federal land for oil shale research. In 2006 and 2007, six leases were given out: five in Colorado and one in Utah. All the Colorado leases were for testing in-situ methods. The Utah lease was for underground mining with surface processing. Shell Oil won three leases. Chevron and EGL Resources each won a lease in Colorado. The Utah lease was won by Enefit American Oil.

In 2010, the government considered three more applications for research leases. However, no leases were given out. They are waiting for the results of a new environmental study ordered by the Obama administration.

In 2011, the Obama administration stopped further oil shale leasing until the study was finished. This was to make sure the lease terms were fair to the government. As of January 2015, the new study has not been released.

Chevron closed its Chevron CRUSH project in 2012. Shell closed its Mahogany Research Project in 2013.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |