History of women in the United Kingdom facts for kids

The history of women in the United Kingdom explores the important roles women have played in British society. It covers how their lives changed over many centuries, including their social, cultural, and political contributions.

Contents

Medieval Times

During the Middle Ages, society in England was mostly run by men. However, women's lives were different depending on their social class, if they were married or not, and where they lived. Women often had a lot of unofficial power in their homes and communities.

Even though men were officially in charge, women played strong roles in culture and spiritual life. They had fewer choices for jobs, trade, and legal rights compared to men. After the Norman invasion, women's rights and roles became clearer. Some women benefited from new laws, while others lost out. Widows, for example, gained the right to own property.

Most women worked in farming. Their jobs became more specific: men usually did the ploughing and field work, while women often managed dairy production. In medieval times, women were also responsible for making and selling ale (a type of beer). However, by the 1600s, men had largely taken over this role. Women then mostly worked serving drinks, which was a lower-status job.

Early Modern Period

Tudor Era

The Tudor era gives us a lot of information about noble women, especially queens. However, we don't have as much information about the daily lives of average women. Still, we know a lot about women's roles in having children from population records.

Compared to other parts of Europe, women in England had more freedom. Visitors from Spain and Italy often commented on this. England also had more well-educated upper-class women than other European countries.

Queen Elizabeth I's decision not to marry was a big political topic. She often said she was "married" to her kingdom and subjects, acting like a mother to her people. This idea of her as a "mother" helped her rule as a female leader.

Healthcare

Even though male doctors didn't always approve, women healers were very important in looking after people in London during the Elizabethan era. They worked for churches, hospitals, and private families. They provided nursing care, medicines, and even some surgical services. Women's roles in healthcare grew even more in the 1600s, especially in caring for the poor. They ran homes for the sick and homeless, and looked after orphaned children and pregnant women. After 1700, new workhouses changed these roles, and parish nurses mostly looked after children.

Marriage

Most English women (and adults in general) got married during this time. On average, brides were about 25–26 years old, and grooms were 27–28. Among rich families, brides married younger, around 19-21. Many women in cities married in their thirties or forties. It was also common for young women who had lost their parents to delay marriage to support younger brothers and sisters. About a quarter of all English brides were pregnant when they got married.

Witchcraft Laws

Laws about witchcraft started in England in 1542. These laws set punishments for practicing witchcraft. In Wales, fears about witchcraft grew around 1500. There was concern about women's magic being used against the government and church. Accusations of witchcraft were also sometimes used against enemies of King Henry VII.

When James I became king in 1603, he brought stricter ideas about witchcraft from Europe. He introduced the Witchcraft Act of 1604, which made witchcraft a serious crime. He believed that women were weaker and more easily influenced by the devil, and that gatherings of women threatened his power.

After 1700, people started to mock beliefs in witches. The Witchcraft Act of 1735 completely changed things. Instead of punishing people for actually practicing witchcraft (which many now thought was impossible), it punished those who pretended to have magical powers. Someone claiming to call spirits or tell the future would be treated as a con artist and could be fined or jailed.

Historians Keith Thomas and Alan Macfarlane studied witchcraft by looking at history and anthropology. They suggested that witchcraft accusations often happened when communities faced problems. Older women were often targeted because they were sometimes on the edges of society and had fewer people to defend them.

Reformation and Religion

The Reformation closed convents and monasteries, and encouraged former monks and nuns to marry. Women also took part in the religious changes. In Scotland, the ideas of Calvinism, which emphasized equality and emotion, appealed to both men and women. Godly men valued the prayers and conversations of their female friends in faith, which led to loving marriages and close friendships. Women also formed stronger connections with ministers and became more involved in prayer groups. For the first time, ordinary women gained many new religious roles.

Industrial Revolution

Historians have different ideas about how the Industrial Revolution and capitalism affected women. Some, like Alice Clark, believe that capitalism had a negative impact. She argued that in the 16th century, women were very involved in farming and industry. Homes were central to production, and women played a key role in running farms and businesses. For example, they brewed beer, made dairy products, raised animals, grew food, spun thread, sewed, and nursed the sick. These useful economic roles gave them a kind of equality with their husbands.

However, Clark argued that as capitalism grew, jobs became more divided. Husbands took paid jobs outside the home, and wives were left with unpaid housework. Middle-class women became confined to their homes, supervising servants. Lower-class women were forced into low-paying jobs.

Others, like Ivy Pinchbeck, believe that capitalism actually helped women gain more freedom. Louise Tilly and Joan Wallach Scott suggested three stages for women's roles in Europe:

- Pre-industrial era: Women produced most of what the family needed at home.

- Early industrialisation: The whole family, including wives and older children, worked to earn money.

- Modern stage: The family became a place for consuming goods, and many women worked in retail and office jobs to support a higher standard of living.

19th Century

Family Life

In the Victorian era, the number of births increased until 1901. This happened for a few reasons. One is that as living standards improved, more women were able to have children. Another reason is that more people got married, and they married at a younger age. This meant more births happened within marriage.

By the early 1900s, birth rates started to level out.

Middle-Class Homes

The Industrial Revolution created a fast-growing middle class. These families usually had one or more servants to cook, clean, and look after children. The middle-class home became a very private place. Before, homes and workplaces were often in the same area. But in the Victorian era, family life became separate from work. The home was seen as a private space for the immediate family.

Working-Class Families

For working-class families, the housewife had to do all the chores that servants did in richer homes. She was responsible for keeping her family clean, warm, and dry, often in very poor housing. In London slums, many families lived in just one room. Rents were high, and some working-class families spent half their income on rent.

Housework for women without servants was very hard. Coal dust from stoves and factories covered everything. Washing clothes meant scrubbing them by hand in a large tub. Curtains were washed every two weeks because they got so black from smoke. Scrubbing the front doorstep every morning was important to show respectability.

Leisure Time

Opportunities for fun activities grew a lot as wages increased and work hours decreased. In cities, a nine-hour workday became common. The Bank Holiday Act 1871 created fixed holidays, and annual holidays became normal, first for the middle class and then for the working class.

About 200 seaside resorts appeared thanks to cheap hotels, affordable train fares, and new holidays. Middle-class Victorians used trains to visit places like Worthing, Brighton, and Scarborough, turning them into big tourist spots. People like Thomas Cook saw tourism as a good business.

By the late Victorian era, the entertainment industry grew in all cities, and many women attended. It offered planned shows at convenient places for low prices, including sports, music halls, and theatre. Women were also allowed to play some sports, like archery, tennis, badminton, and gymnastics.

Women's Rights and Changes

The 19th century brought new chances for people to improve society, and this led to the start of the feminist movement. The first organized group for women's right to vote in Britain was the Langham Place Circle in the 1850s. Led by Barbara Bodichon and Bessie Rayner Parkes, they also fought for better rights for women in law, jobs, education, and marriage.

Women who owned property and widows used to be able to vote in some local elections, but this ended in 1835. The Chartist Movement asked for voting rights, but only for men. Rich women could sometimes influence politics behind the scenes in high society.

Child Custody

Before 1839, if rich women got divorced, they usually lost their children. The children would stay with the father, who was the head of the household. Caroline Norton experienced this when she was denied access to her three sons after her divorce. This personal tragedy led her to campaign intensely. Her efforts helped pass the Custody of Infants Act 1839. This law gave women, for the first time, some rights to their children and allowed judges to make decisions in child custody cases. It also created the "tender years doctrine," which suggested that young children (under seven) should stay with their mothers, while fathers remained responsible for financial support. In 1873, Parliament extended this to children up to sixteen years old. This idea spread to many parts of the world because of the British Empire.

Divorce Laws

Before 1857, divorce in Britain was almost impossible for most people. It required a very expensive special act of Parliament, which only the richest could afford. It was also very hard to get a divorce based on unfaithfulness, abandonment, or cruelty.

A big change came with the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. This law made divorce a civil matter handled by courts, not the Church. A new civil court in London dealt with all cases. It was still quite expensive, but now middle-class people could afford it. A woman who got a legal separation gained full control of her own rights. More changes came in 1878, allowing local judges to handle separations. The Church of England blocked further reforms until the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 finally brought more changes.

Property Rights

A series of four laws called the Married Women's Property Act were passed between 1870 and 1882. These laws removed rules that stopped wealthy married women from controlling their own property. They now had almost equal status with their husbands, and more rights than women in other parts of Europe. Working-class women were also protected by laws that assumed they needed government help, similar to children.

Job Opportunities

The rapid growth of factories created job opportunities for women in light industries like textiles, clothing, and food production. There was a lot of interest in the new status of women workers. In Scotland, St Andrews University was a pioneer in allowing women to attend universities, creating a special degree for women. From 1892, Scottish universities could admit and graduate women, and the number of women attending steadily increased.

Middle-Class Jobs

Ambitious middle-class women faced big challenges in finding suitable careers, such as nursing, teaching, law, and medicine. Doctors made it very hard for women to enter medicine. There were few places for women as lawyers, and none as religious leaders.

In the 1870s, a new job opened up for women in libraries. It was said that these tasks were "Eminently Suited to Girls and Women." By 1920, women and men were equally represented in the library profession. By 1930, women were ahead, and by 1960, they made up 80% of librarians. This change happened due to factors like losses from World War I, new laws, library-building efforts, and groups advocating for women's employment.

Teaching

Teaching was also a growing field for women. The lower salaries were less of a problem for single women than for married men. By the late 1860s, many schools were training women to be governesses or teachers. In 1851, about 70,000 women in England and Wales were teachers. By 1901, this number grew to 170,000, making up three-fourths of all teachers. Most came from lower middle-class backgrounds. The National Union of Women Teachers (NUWT) was formed in the early 1900s within the male-controlled National Union of Teachers (NUT). It demanded equal pay for women teachers and eventually became a separate group. While Oxford and Cambridge universities limited women's roles, new universities in other major cities were more open to women.

Nursing and Medicine

Florence Nightingale showed how important professional nursing was during wartime. She set up a training system that guided women into nursing in the second half of the 19th century. By 1900, nursing was a very appealing career for middle-class women.

Medicine was a much harder field for women to enter because men controlled it tightly. One way for women to become doctors was to go to the United States, where there were schools for women as early as 1850. Britain was one of the last major countries to train women doctors. Edinburgh University admitted a few women in 1869 but then changed its mind in 1873, causing strong negative reactions among British medical educators. The first separate school for women doctors opened in London in 1874 with only a few students. In 1877, a college in Ireland became the first to admit women for medical licenses. Full coeducation in medicine didn't happen until World War I.

Poverty for Working-Class Women

The 1834 Poor Law decided who could receive financial help. This law showed and continued the existing gender roles. In Edwardian society, men were seen as the main earners. The law limited help for unemployed, able-bodied men, believing they would find work without money. However, women were treated differently. After the Poor Law, women and children received most of the aid. The law did not recognize single independent women and grouped women and children together. If a man was disabled, his wife was also treated as disabled under the law. Unmarried mothers were often sent to workhouses and faced unfair social treatment. In marriage disputes, women often lost rights to their children, even if their husbands were abusive.

At the time, single mothers were the poorest group in society for several reasons. First, women lived longer, often becoming widows with children. Second, women had few job opportunities, and when they found work, their wages were lower than men's. Third, women were less likely to remarry after being widowed, leaving them as the sole providers for their families. Finally, poor women often had poor diets because their husbands and children received more food. Many women were malnourished and had limited access to healthcare.

20th Century

Women in the Edwardian Era

The Edwardian era, from the 1890s to World War I, saw middle-class women breaking free from Victorian limits. Women had more job opportunities and were more active. Many worked worldwide in the British Empire or for religious groups.

Housewives

For housewives, sewing machines made it easier to buy ready-made clothes or sew their own. This helped women adapt to changes in their lives. More women in the middle class could read, giving them access to more information and ideas. Many new magazines appeared that appealed to women and helped define what being feminine meant.

Office Jobs

New inventions like the typewriter, telephone, and new filing systems created more job opportunities for middle-class women. The rapid growth of schools and the new profession of nursing also provided jobs. Better education and status led to demands for women's roles in the growing world of sports.

Women's Right to Vote

As middle-class women gained status, they increasingly supported demands for a political voice.

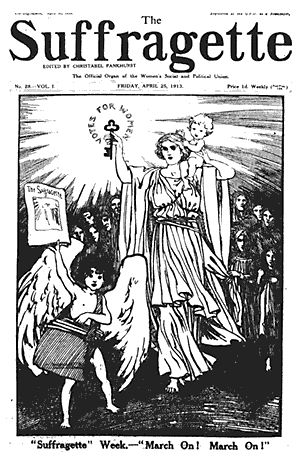

In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst founded the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), a group that fought for women's right to vote. The WSPU was the most famous group, but there were many others, like the Women's Freedom League and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett. In Wales, women fighting for the vote were sometimes treated badly and even violently when they protested.

The protests became more extreme, including heckling, breaking shop windows, burning mailboxes, and setting fire to empty buildings. Emily Davison, a WSPU member, died after running onto the track during the 1913 Epsom Derby. These actions created mixed reactions: some people sympathized, while others were turned off. Many protesters were jailed and went on hunger strike, which caused problems for the government. Through these actions, the suffragists successfully brought attention to the unfair treatment of women.

Historians generally agree that the militant suffragette movement in 1906 had a big impact on the suffrage movement. Women were excited by the protests. However, to stay in the news, the protests had to keep getting more extreme. The hunger strikes and force-feeding did this. But the Pankhursts refused advice and escalated their tactics, including disrupting Liberal Party meetings and damaging public buildings. This went too far for many moderate suffragists, who felt the extreme actions were hurting the cause.

When World War I started, the Pankhursts stopped their militant actions and strongly supported the war effort. Their leadership role ended. Women finally gained the right to vote in Britain on the same terms as men in 1928. In Wales, women's involvement in politics grew steadily from 1907. By 2003, half the members elected to the National Assembly were women.

Female Servants

Edwardian Britain had many male and female domestic servants in both cities and rural areas. Servants were given food, clothing, housing, and a small wage. They lived in a self-contained social system within the wealthy homes. The number of domestic servants decreased in the Edwardian period because fewer young people wanted these jobs.

Fashion

The upper classes enjoyed leisure sports, which led to quick changes in fashion. More flexible clothing styles were needed. During the Edwardian era, women wore very tight corsets and long skirts. This was the last time corsets were worn daily. After World War I, women's clothing changed dramatically, with skirts becoming much shorter.

New styles in clothing design emerged. The heavy fabrics and bustles of the previous century disappeared. New, tight-fitting skirts and dresses made of lightweight fabrics were introduced for a more active lifestyle.

- Two-piece dresses became popular. Skirts were tight at the hips and flared out at the bottom, like a trumpet or lily.

- In 1901, skirts had decorated hems with ruffles and lace.

- Some dresses and skirts had trains.

- Tailored jackets, first seen in 1880, became more popular, and by 1900, tailored suits were common.

- By 1904, skirts became fuller and less clingy.

- In 1905, skirts fell in soft folds that curved in and then flared out near the hem.

- From 1905 to 1907, waistlines rose.

- In 1901, the hobble skirt was introduced; it was a tight skirt that made it hard for women to take long steps.

- Lingerie dresses, or tea gowns made of soft fabrics with ruffles and lace, were worn indoors.

First World War

World War I helped the cause of women's rights, as women's hard work and paid jobs were greatly valued. Prime Minister David Lloyd George clearly stated how important women were:

It would have been utterly impossible for us to have waged a successful war had it not been for the skill and ardour, enthusiasm and industry which the women of this country have thrown into the war.

The militant suffragette movement stopped during the war and never restarted. British society believed that the new patriotic roles women played earned them the right to vote in 1918. However, historians now suggest that giving soldiers the vote first, and women second, was decided by politicians in 1916. Women in Britain finally achieved the right to vote on the same terms as men in 1928.

After the war, clothing rules became more relaxed. By 1920, there was talk about young women called "flappers" who were seen as showing off their looks.

Social Changes

Getting the vote did not immediately change social conditions. With the economic recession, women were the most vulnerable group in the workforce. Some women who had jobs before the war had to give them up to returning soldiers.

After gaining the vote, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) became the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC). This new group still fought for equal voting rights but also worked for equality in social and economic areas. They wanted to change unfair laws, like family law, and address the differences between "equality" and "equity" (meaning what women needed to overcome barriers). Eleanor Rathbone, who became a Member of Parliament in 1929, led NUSEC in 1919. She emphasized that women needed to fulfill their own potential.

Important laws during this time included the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 (which opened professions to women) and the Matrimonial Causes Act 1923. In 1932, NUSEC split its work into advocacy and education, continuing as the National Council for Equal Citizenship and the Townswomen's Guild.

Second World War

Britain's full effort during World War II helped win the war by keeping strong public support. The war was seen as a "people's war" that increased hopes for a welfare state after the war.

Historians praise Britain for successfully organizing its home front for the war. This included getting the most workers possible, maximizing production, putting the right skills to the right tasks, and keeping up people's spirits. Much of this success was due to the planned use of women as workers, soldiers, and housewives, which became mandatory after December 1941. Women supported the war effort and made the rationing of goods successful. The government's success in providing new services, like hospitals and school lunches, along with the idea of a "People's War," led to widespread support for a larger welfare state.

Parents had less time to supervise their children, and there was concern about young people getting into trouble, especially as older teenagers took jobs. The government responded by requiring all youth over 16 to register and by increasing the number of clubs and organizations for them.

Rationing

Items like food, clothing, petrol, and leather were rationed. However, things like sweets and fruits were not rationed because they would spoil. Access to luxury items was very limited, though there was a black market. Families also grew "victory gardens" (small home vegetable gardens) to grow their own food. Many things were saved to be turned into weapons later, like fat for making explosives. People in the countryside were less affected by rationing because they had more access to local, unrationed products than people in cities.

The rationing system improved by switching to a points system, which allowed housewives to choose what they needed most. Food rationing also helped improve the quality of available food, and housewives approved, except for the lack of white bread and the government's unpopular "national loaf" (a type of wheat bread). People were especially happy that rationing brought equality and guaranteed a decent meal at an affordable price.

1950s

The 1950s in Britain were a quiet time for active feminism. After World War II, there was a new focus on marriage and the nuclear family as the basis of the new welfare state.

In 1951, 75% of adult women were married or had been married. A popular book for women in 1953 stated that "A happy marriage... [is] the best course, the simplest, and the easiest way of life for us all."

After the war, childcare facilities closed, and help for working women became limited. However, the new welfare state introduced family allowances to help families, supporting women in their roles as wives and mothers. Some historians argue that the vision for a "New Britain" in 1945 had a traditional view of women.

Women's commitment to marriage was also shown in popular media like films, radio, and women's magazines. In the 1950s, women's magazines had a big influence on opinions, including views on women's employment.

Despite this, the 1950s saw some progress for women, such as equal pay for teachers (1952) and for men and women in the civil service (1954). This was thanks to activists like Edith Summerskill, who fought for women's causes.

Feminist writers of that time, like Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, started to consider that women should be able to combine home life with outside jobs. Feminism in 1950s England was strongly linked to social responsibility and the well-being of society as a whole. This often meant that the personal freedom of self-declared feminists was less emphasized. Even women who called themselves feminists strongly supported the idea that children's needs came first.

Political Roles

Women's political roles grew in the 20th century after the first woman entered Parliament in 1919. The 1945 election tripled their number to twenty-four, but then it stayed at that level for a while. The next big jump came in 1997, when 120 women were elected as Members of Parliament (MPs). Since then, women have made up about 20 percent of the House of Commons. The 2015 election saw a peak of 191 women elected.

The BBC radio program "Woman's Hour" started in 1946. It covered fashion, glamour, housekeeping, family health, and child-rearing. It also tried to encourage a sense of citizenship among its middle-class audience. Working with groups like the National Council of Women (NCW) and the National Federation of Women's Institutes (NFWI), the program featured current events, public debates, and national politics. It also brought women MPs to speak on air.

21st Century

From 2007 to 2015, Harriet Harman was Deputy Leader of the Labour Party. Traditionally, this role meant being Deputy Prime Minister. However, Gordon Brown decided not to have a Deputy Prime Minister. Harman did hold the cabinet post of Leader of the House of Commons, and Brown allowed her to lead Prime Minister's Questions when he was away. Harman also served as Minister for Women and Equality.

In April 2012, English journalist Laura Bates started the Everyday Sexism Project. This website collects examples of sexism that people experience daily from around the world. The site quickly became popular, and a book based on its submissions was published in 2014. In 2013, the first collection of spoken stories about the United Kingdom women's liberation movement (called Sisterhood and After) was launched by the British Library.

See also

Topics

- Economic history of the United Kingdom, after 1700

- Feminism in the United Kingdom

- Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp

- Historiography of the British Empire

- Historiography of the United Kingdom

- List of female members of the House of Lords

- Social history of England

- Social history of the United Kingdom (1945–present)

- Suffrage in the United Kingdom

- The Women's Peace Crusade

- Timeline of Female MPs in the House of Commons

- Women in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

- Women in the House of Lords

- Women in the Victorian era

- Women in World War I (Great Britain)

- Home front during World War I (Britain)

- Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom

Scotland

- Historiography of Scotland

- Women in early modern Scotland

- Women in Medieval Scotland

Wales

- Women's suffrage in Wales

Categories

- British suffragists

- British women

- English women

- Scottish women

- Welsh women

- Women from Northern Ireland

- Women in Scotland

Organisations

- British Federation of University Women (BFUW), founded in 1907.

- NASUWT, The National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers, formed 1976

- National Council of Women of Great Britain

- National Union of Women Teachers, formed 1904

- Adelaide Anne Procter (1825–1864) writer on behalf of unemployed women

- Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps, unit in First World War

- Society for Promoting the Employment of Women (SPEW), formed 1859; in 1926 renamed the Society for Promoting the Training of Women (SPTW)

- Townswomen's Guild, formed 1929

- Women's Freedom League

- Women's Institutes

- Scottish Women's Institutes, formed in 1917

- Women's Social and Political Union, suffragists of early 20th century

Individuals

- Margaret Bondfield (1873–1953) women's rights activist

- Edith Balfour Lyttelton (1865–1948) novelist, activist and spiritualist.

- Mary Macarthur (1880–1921) trade unionist and women's rights campaigner.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |