Husein Gradaščević facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Husein Gradaščević

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Dragon of Bosnia |

| Born | 31 August 1802 Gradačac, Bosnia Eyalet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 17 August 1834 (aged 31) Golden Horn, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Buried |

Eyüp Cemetery, Istanbul

|

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Kosovo (1831) Herzegovina campaign |

| Children | Muhamed-beg Gradaščević Šefika Gradaščević |

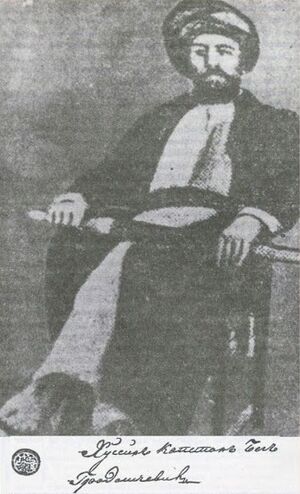

Husein Gradaščević (Husein-kapetan) was an important military leader in Ottoman Bosnia. He lived from 1802 to 1834. He is famous for leading an uprising against the Ottoman Empire's attempts to change things. These changes, called the Tanzimat reforms, aimed to make the empire more modern.

Husein was born into a noble family in Bosnia. In the early 1820s, he became the captain of Gradačac, taking over from his family members. He grew up during a time of big changes and problems in the western parts of the Ottoman Empire. His importance grew during the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29). The Bosnian governor asked him to gather an army.

By 1830, Gradaščević became the main voice for all Ottoman captains in Bosnia. He helped organize defenses against a possible invasion from Serbia. The Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II introduced reforms that upset many. These reforms got rid of the Janissaries (special soldiers) and reduced the power of the noble families. Also, the Sultan gave more freedom and land to Serbia. Because of this, many Bosnian nobles joined together and revolted.

Gradaščević was chosen as their leader and even claimed the title of Vizier (a high-ranking official). This uprising aimed for Bosnia to have more self-rule. It lasted three years and involved fighting against those loyal to the Ottoman Empire, especially in Herzegovina. One of Gradaščević's big achievements was leading his forces to victory against the Ottoman army in Kosovo. However, the uprising eventually failed. All the captaincies were ended by 1835. Gradaščević was sent away to Austria for a short time. He then made a deal with the Sultan to return to the Ottoman Empire, but he was not allowed back in Bosnia. He died in 1834 under mysterious circumstances and was buried in Eyüp Cemetery in Istanbul.

Husein Gradaščević is known as "the Dragon of Bosnia" (Zmaj od Bosne). He is seen as a Bosniak national hero.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Husein Gradaščević's family came from Buda (in modern-day Hungary) to Bosnia in the late 1600s.

Husein was born in 1802 in Gradačac, a town in northern Bosnia. His parents were Osman and Touley-hanuma. We don't know much about his childhood, but he likely spent time around his family's fort. He grew up during a time of trouble. His father was a military man, and his brother Osman fought in a war against Serbia in 1813. These stories probably shaped young Husein.

Husein's father, Osman, died in 1812 when Husein was only ten years old. Husein became the head of the Gradačac military captaincy after his older brother Murat was poisoned in 1821. This happened because rival nobles wanted to gain favor with the Grand Vizier (a top Ottoman official).

Husein married Hanifa, the sister of Captain Mahmud of Derventa. They had a son, Muhamed-beg Gradaščević, who was likely born around 1822. They also had a daughter, Šefika, born in 1833. Neither of his children are known to have had their own children.

Becoming a Leader in Gradačac

When Husein became the captain of Gradačac, he focused on managing the area. He built many things in and around Gradačac. Under his leadership, Gradačac became one of the richest captaincies in Bosnia.

One important project was the Gradačac Castle. The fort had been there for a long time and was often repaired. Husein likely did a major renovation of the castle's tower.

Husein also built a new castle called Čardak. It had an artificial island surrounded by a wide, deep moat. The castle was seventeen meters long and eight meters wide. The area also included a mosque, wells, and hunting grounds.

Inside Gradačac city, Husein's most famous building was the clock tower (Bosnian: sahat-kula), built in 1824. It was the last clock tower of its kind built in Bosnia.

Just outside the city walls, Husein built the Husejnija mosque in 1826. It has an eight-sided dome roof and a tall minaret (25 meters high). The mosque has beautiful Islamic designs.

Husein was known for being fair to the Christian people in his area, both Catholic and Orthodox. Even though the Sultan's approval was usually needed for non-Islamic religious buildings, Husein allowed several to be built without it. A Catholic school was built in Tolisa in 1823. A large church for 1,500 people followed. Two more Catholic churches were built in Dubrave and Garevac, and an Orthodox church in Obudovac. Christians in Gradačac were very happy during Husein's time as captain.

Husein became more involved in Bosnian politics in 1827. This was because of the coming Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) and his role in preparing Bosnia's defenses. He gathered people from Gradačac and made his defenses stronger. He was put in charge of an army to be gathered between the Drina and Vrbas rivers. He did a good job. In 1828, he even helped the Bosnian vizier (governor) escape to safety after a soldier revolt.

By 1830, Husein had become so important that he could speak for most of Bosnia's captains. He organized Bosnia's defense against a possible invasion by Serbia. He also warned Austrian authorities not to cross the Sava river. His strong leadership in Gradačac showed the big role he would play later.

The Bosnian Uprising Begins

In the late 1820s, Sultan Mahmud II started new reforms. These reforms aimed to expand the central army, collect new taxes, and create more Ottoman government offices. These changes reduced the special status and benefits of the Bosnian Muslim nobles. Many Bosnian leaders were also unhappy because the Ottomans didn't help Muslim refugees from Serbia. Husein Gradaščević was not strongly against these reforms at first.

In 1826, Sultan Mahmud II got rid of the Janissaries by force. He also banned the Bektashi Order and sent his commanders to fight against important Balkan Muslim leaders. This caused a lot of problems. Gradaščević's first reaction to the Janissaries being removed was similar to other Bosnian nobles. He threatened to use military force against anyone who opposed the Sarajevo Janissaries. However, when the Janissaries killed a religious leader, Gradaščević changed his mind and moved away from their cause. He realized that money problems were the main reason for the Janissaries' unhappiness. After this, Gradaščević generally got along well with the Ottoman authorities in Bosnia.

The big change for Gradaščević came with the end of the Russo-Ottoman War and the Treaty of Adrianople (1829) in 1829. This treaty forced the Ottoman Empire to give more freedom to Serbia and give it six districts. This made the Bosnian nobles very angry, and they protested a lot.

Between December 20 and 31, 1830, Gradaščević hosted a meeting of Bosnian nobles in Gradačac. A month later, another meeting was held in Tuzla to plan a revolt. From there, a call went out to the Bosnian Muslim people, asking them to defend Bosnia. Gradaščević was then unofficially chosen to lead the rebellion. Their demands from Constantinople were:

- Take back the special rights given to Serbia and return the six districts to Bosnia.

- Stop the new military reforms.

- End the rule of the Ottoman governor in Bosnia. Instead, they wanted an independent Bosnian government led by a local leader. In return, Bosnia would pay a yearly tax.

Another decision at the Tuzla meeting was to hold a bigger meeting in Travnik. Since Travnik was where the Ottoman governor lived, this meeting was a direct challenge to Ottoman rule. Gradaščević asked everyone to help gather an army. On March 29, 1831, Gradaščević marched towards Travnik with about 4,000 men.

When the Ottoman governor, Namık Pasha, heard about the army, he went to the Travnik fort. The rebel army fired warning shots at the castle. Gradaščević sent some of his forces to meet the governor's reinforcements. They fought near Travnik on April 7. Gradaščević's forces won, forcing the governor's allies to retreat. On May 21, Namık Pasha fled to Stolac after a short siege. Soon after, Husein Gradaščević was proudly named the "commander of Bosnia, chosen by the will of the people." On May 31, he asked all Bosnian nobles to join his army. Thousands joined him, including many Christians, who made up about a third of his forces. Gradaščević split his army. He left one part in Zvornik to defend against a possible Serbian attack. With the main army, he went to Kosovo to meet the Grand Vizier, who had been sent with a large army to stop the rebellion. On the way, he took the city of Peć with 25,000 soldiers and then went to Priština, where he set up his main camp.

The battle with Grand Vizier Reşid Mehmed Pasha happened on July 18 near Štimlje. Both armies were about the same size, but the Grand Vizier's troops had better weapons. Gradaščević sent part of his army forward. After a small fight, they pretended to retreat. Thinking they had won, the Grand Vizier sent his cavalry and artillery into a forest. Gradaščević quickly used this mistake to his advantage. He launched a strong counterattack, almost destroying the Ottoman forces. Reşid Pasha himself was hurt and barely escaped.

The Grand Vizier claimed that the Sultan would agree to all Bosnian demands if the rebel army went home. So, Gradaščević and his army turned back. On August 10, the rebel leaders met in Priština and decided that Gradaščević should be declared Vizier of Bosnia. Gradaščević refused at first but finally accepted. This was made official at a meeting in Sarajevo on September 12. In front of the Tsar's Mosque, everyone swore to be loyal to Gradaščević. They said there would be no turning back, even if they failed or died.

At this point, Gradaščević was not only the top military commander but also Bosnia's main civilian leader. He set up a government around him. After staying in Sarajevo, he moved the center of Bosnian politics to Travnik, making it the capital of the rebel state. In Travnik, he created a divan (a Bosnian congress) which, with him, formed the Bosnian government. Gradaščević also collected taxes and dealt with local people who opposed the self-rule movement. He became known as a hero and a strong, brave, and determined ruler.

During a break in fighting with the Ottomans, attention turned to the strong opposition in Herzegovina. A small campaign was launched against that region from three directions. However, the attack on Gacko failed. One success was in October when Husein Gradaščević sent an army that tried to capture Trebinje.

A Bosnian group went to the Grand Vizier's camp in Skopje in November. They were promised that the Grand Vizier would ask the Sultan to accept Bosnian demands and make Gradaščević the official Vizier of an independent Bosnia. However, the Grand Vizier's true plans became clear in early December when he attacked Bosnian rebel units near Novi Pazar. The rebel army defeated the imperial forces again. But because of a very cold winter, the Bosnian troops had to go home.

Meanwhile, in Bosnia, Gradaščević decided to continue his campaign against the captains in Herzegovina who were loyal to the Sultan, even though the weather was bad. The captain of Livno was ordered to launch a final attack to end all local opposition. This captain attacked Ljubuški and won, securing most of Herzegovina except Stolac. However, the rebel groups that surrounded the Stolac Fortress faced cannon fire and ambushes. Husein Gradaščević sent another army towards Stolac from Sarajevo, but it was called back on March 16. This was because news arrived that the Grand Vizier was planning a major attack on Bosnia.

The Ottoman attack began in early February. The Grand Vizier sent two armies towards Sarajevo. Gradaščević sent an army of about 10,000 men to meet them. When the Vizier's troops crossed the Drina river, Gradaščević ordered 6,000 men to meet them in Rogatica. Other units went to Pale near Sarajevo. The two sides finally met on the Glasinac plains east of Sarajevo in late May. Husein Gradaščević led the Bosnian army himself. In this first fight, Gradaščević had to retreat to Pale. The fighting continued in Pale, and Gradaščević had to retreat again, this time to Sarajevo. There, the captains decided to keep fighting.

By 1832, after many smaller fights, a big battle happened outside Sarajevo. Husein Gradaščević was winning at first. But then, Serbian rebels arrived and joined the forces of Mahmud II. This turned the tide.

The final battle took place on June 4 at Stup, near Sarajevo. After a long, intense fight, it looked like Gradaščević had won again. But near the very end, troops from Herzegovina, who were loyal to the Sultan, broke through Gradaščević's defenses. They joined the fight from behind. The rebel army was caught off guard and had to retreat into Sarajevo. They decided that fighting more would be useless. Gradaščević fled to Gradačac. The imperial army entered Sarajevo on June 5 and prepared to march on Travnik. Realizing the problems his family would face if he stayed, Gradaščević decided to leave Gradačac and go to Austrian lands.

Life in Exile and Death

The Sultan was very angry and declared Gradaščević a "traitor" and "rebel." This likely convinced Gradaščević to leave Bosnia. After some delays, Gradaščević finally reached the Sava River border on June 16 with many followers. He crossed into Habsburg lands that same day with about 100 followers, servants, and family. He expected to be treated like a Bosnian vizier. Instead, he was held in quarantine in Slavonski Brod for almost a month. His weapons and many belongings were taken away.

Gradaščević and other rebels managed to escape across the Sava to Vinkovci and then to Osijek, in Austrian territory. About 66 men, 12 women, 135 servants, and 252 horses were with him.

Austrian officials were pressured by the Ottoman government to move Gradaščević far away from the border. On July 4, he was moved to Osijek, where he was basically held captive. His communication with his family and friends was very limited. He complained about his treatment several times. His conditions eventually got better. Before he left Osijek, he told local officials that he had enjoyed his stay there. Even though he missed home very much and wasn't fully in control of his life, Gradaščević kept his pride. He was said to have lived a fancy life, even having jousting competitions with his friends.

In late 1832, he agreed to return to Ottoman territory to receive a pardon from the Sultan. The terms, read to him in Zemun, were very strict. They said Gradaščević could never return to Bosnia. He also could never set foot on the European lands of the Ottoman Empire. Disappointed, Gradaščević had to obey. He rode to Belgrade. He entered the city on October 14 like a true vizier, riding a horse decorated with silver and gold, with a large group of people. Muslims in Belgrade greeted him as a hero. The local governor treated him as an equal. Gradaščević stayed in Belgrade for two months, and his health got worse. He left the city for Constantinople in December. His wife, whose daughter was still very young, stayed in Belgrade and joined him the next spring.

In Constantinople, Gradaščević lived in old army barracks. His family lived in a separate house nearby. He lived a relatively quiet life for the next two years. The only notable event was when the Sultan offered him a high-ranking position in the army. Gradaščević refused this offer.

He died in Constantinople in 1834 at the age of 32.

His Lasting Impact

After his death, Husein Gradaščević became a symbol of Bosnian pride. People used to say that for years after he died, no one could hear his name without shedding a tear. This positive feeling was not just among Muslims. Christians from Posavina also felt similarly for decades.

Even though most Bosniaks in Herzegovina supported Husein Gradaščević, some local leaders, like Ali-paša Rizvanbegović, supported Sultan Mahmud II for their own benefit. In the years after, these Herzegovinian leaders suffered during the Herzegovina Uprising (1875–1878). This was mainly because there was no strong central leader in Bosnia Eyalet.

The first historical writings about Gradaščević appeared in 1900. Later, in 1901, he was mentioned in works about the first Serbian Uprising. These writings showed Gradaščević as a tragic hero.

For many decades, historians generally believed that Gradaščević's movement was just the Bosnian upper class reacting to the Sultan's reforms. During World War II, there was a brief interest in bringing his remains back to Sarajevo.

During the time of Communist Yugoslavia, Gradaščević and his movement were rarely talked about. The idea of the upper class resisting modern reforms didn't fit with communist ideas. It wasn't until 1988 that Gradaščević was mentioned again in a significant way.

Since the Yugoslav Wars and the Bosniak National Awakening, Gradaščević and his movement have become very popular again among historians and the public. New historical works have shown Gradaščević in a more positive light. Today, Gradaščević is widely seen as the greatest Bosniak national hero. He is a symbol of national pride and spirit. The main streets in Gradačac and Sarajevo, as well as many other places in Bosnia and Herzegovina, are named after him.

Annotations

See also

In Spanish: Husein Gradaščević para niños

In Spanish: Husein Gradaščević para niños