Inaugural games of the Colosseum facts for kids

The very first games at the Colosseum were a huge celebration! They were ordered by the Roman Emperor Titus to mark the completion of the Colosseum in AD 80. Back then, it was called the Flavian Amphitheatre (Latin: Amphitheatrum Flavium).

Titus's father, Vespasian, started building this amazing amphitheatre around AD 70. Titus finished it after his father passed away in AD 79. Titus's rule began with some tough times, including the famous Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, a big fire in Rome, and a plague. To make people feel better and perhaps please the gods, Titus opened the Colosseum with incredible games that lasted over one hundred days!

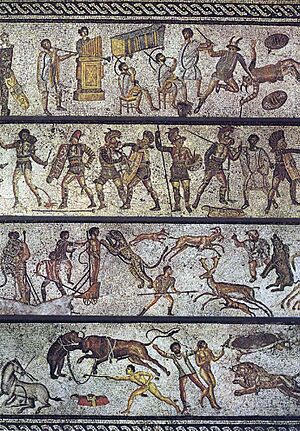

We don't have many detailed records of the gladiatorial training and fights (called ludi). But they likely followed the usual plan for Roman games:

- Morning: Animal shows.

- Midday: Executions of criminals.

- Afternoon: Gladiator fights and re-enactments of famous battles.

The animal shows featured creatures from all over the Roman Empire. There were exciting hunts and fights between different animal species. Animals were also part of some executions, which were staged like scenes from myths or history. Even naval battles were part of the shows! Historians still debate if these took place inside the Colosseum or on a special lake built by Augustus.

Only a few accounts from that time or soon after survive. The writings of Suetonius and Cassius Dio focus on the main events. Martial gives us some small details about individual shows. He also provides the only known detailed record of a gladiator fight: the battle between Verus and Priscus.

Contents

Background of the Games

Building the Colosseum

The Colosseum was built in a low valley surrounded by the Caelian, Esquiline, and Palatine hills. This area became available after the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64. Emperor Nero had used it for his own pleasure, building a huge artificial lake and a giant statue of himself.

Vespasian began building the Colosseum around AD 70-72. He might have paid for it with treasures taken after the Roman victory in the First Jewish-Roman War in AD 70. The lake was filled in, and the site was chosen for the Flavian Amphitheatre. Turning Nero's private land into a public Colosseum made Vespasian very popular. Gladiator schools (ludi) and other support buildings were later constructed in the area where Nero's palace once stood.

Vespasian died when the Colosseum had reached its third story. Within a year, Titus finished building the amphitheatre and the nearby public baths, which were named the Baths of Titus.

Titus's Time as Emperor

By the time the Colosseum was finished, Titus had already faced many challenges. Two months after he became emperor, Mount Vesuvius erupted, destroying cities like Pompeii and Herculaneum. A fire also burned in Rome for three days, causing great damage. There was also a terrible outbreak of plague. To dedicate the Colosseum and the baths, and to calm the Roman people and the gods, Titus held grand games that lasted over a hundred days.

What We Know from Old Writings

Not many detailed records of the games still exist. Writings from that time mostly mention the main events, especially those on the opening days. The poet Martial gives the most complete account in his work De Spectaculis ("On the Spectacles"). This book is a series of poems praising Titus and describing the individual events. Martial's work helps us learn about events not covered by other writers. It also gives us the only known full record of a gladiatorial combat in the arena.

The historian Suetonius was born around AD 70. He started writing about AD 100. He was a child during the games and might have seen them himself. His book Lives of the Caesars, finished around AD 117-127, includes some details about the opening days. Suetonius is generally seen as a careful scholar.

Another important source is Cassius Dio, who lived later, in the second and third centuries. His History of Rome covers 80 books, though many are only fragments. He is known for his attention to small details, but for big events, his writing can be more about his own thoughts than exact facts. His account of Titus's games does not say where he got his information.

Animal Shows

Animal shows were a big part of the games and usually happened in the morning. Dio says that over 9,000 tame and wild animals were killed during the opening games. Some were even killed by women. However, another historian, Eutropius, wrote later that 5,000 animals were killed.

Dio and Martial mention some of the animals shown. Dio notes a hunt with cranes and another with four elephants. Martial talks about elephants, lions, leopards, a tiger, hares, pigs, bulls, bears, wild boar, a rhinoceros, buffalo, and bison. Other exotic animals like ostriches, camels, and crocodiles were often used in games, but are not specifically mentioned for Titus's games. Giraffes were very rare in Rome at that time.

Martial describes a fight between an elephant and a bull. The elephant won and then knelt before Titus. Martial said this showed the elephant recognized the Emperor's power, but it might have been part of its training.

Sometimes, animals didn't act as expected. Martial wrote that Caesar's lions ignored their prey, and a hare played safely near their huge jaws. The rhinoceros was also hard to control. It was first paraded around the arena, then became angry and attacked a bull, which the crowd loved. Later, when it was supposed to fight, it had calmed down. Trainers had to encourage it to fight other animals.

...at length the fury we once knew returned. For with his double horn he tossed a heavy bear as a bull tosses dummies from his head to the stars. [With how sure a stroke does the strong hand of Carpophorus, still a youth, aim the Norcian spears!] He lifted two steers with his mobile neck, to him yielded the fierce buffalo and the bison. A panther fleeing before him ran headlong upon the spears.

Carpophorus was a skilled bestiarius, a fighter who specialized in battling animals. Martial compares him to Hercules and praises his skill in killing a bear, a leopard, and a very large lion. A carving from the Temple of Vespasian and Titus shows scenes like those Martial described: a rhinoceros fighting a bull, and a bestarius (possibly Carpophorus) with a spear facing a lion and a leopard. Other beast slayers were also famous, including a woman who was said to equal Hercules's feat of killing the Nemean Lion.

Some animal trainers faced danger. One trainer was attacked by his lion. But others were successful. One trainer was known for his tigress, which was tame enough to lick his hand but had torn a lion to pieces. The crowd also enjoyed seeing a bull lifted high in the arena, though Martial doesn't explain how this was done.

Executions

Executions were a regular part of Roman games. They usually happened around midday, between the morning animal shows and the afternoon gladiator fights. These executions showed Rome's power. However, people from the higher classes often left the arena during this time to eat lunch.

Fights, Hunts, and Races

Dio, Suetonius, and Martial all mention naumachiae, which were re-enactments of famous sea battles. Dio says that both a special lake built by Augustus and the Colosseum itself were flooded for two different shows. Suetonius only says the event took place on the old artificial lake. Martial doesn't say exactly where the naumachiae happened, but he makes it clear that the location could be flooded and drained easily:

If you are here from a distant land, a late spectator for whom this was the first day of the sacred show, let not the naval warfare deceive you with its ships, and the water like to a sea: here but lately was land. Don't you believe it? Watch while the waters weary Mars. But a short while hence you will be saying "But here lately was sea."

It would have been hard to flood the Colosseum, but since we have few records of how it worked, we can't be sure where the naval battles took place. Suetonius writes that Titus's brother, Domitian, staged sea-fights in the amphitheatre. But Domitian had made changes to the building, likely adding the hypogeum—a complex of underground passages that might have allowed the arena to be quickly flooded and emptied.

While Suetonius only says Titus held naval battle re-enactments, Dio gives some details:

For Titus suddenly filled this same theatre with water and brought in horses and bulls and some other domesticated animals that had been taught to behave in the liquid element just as on land. He also brought in people on ships, who engaged in a sea-fight there, impersonating the Corcyreans and Corinthians; and others gave a similar exhibition outside the city in the grove of Gaius and Lucius, a place which Augustus had once excavated for this very purpose.

Both Dio and Suetonius agree that gladiator contests and wild-beast hunts, called venatio, also happened at the lake area. But they disagree on the details. Dio says this happened on the first day, with the lake covered with planks and wooden stands. Suetonius says the events happened in the basin after the water was drained. Suetonius writes that 5,000 animals were killed there in one day. While we don't have a list of animals hunted there, larger exotic animals like elephants, big cats, and bears were popular. Smaller animals like birds, rabbits, and goats were also used.

Suetonius writes that when Domitian held his games, there were other shows besides the "usual two-horse chariot races." This suggests these races were probably part of Titus's games. Dio tells us there was a horse race on the second day, but he gives no details.

Only Dio's record describes the third day specifically. He says:

…there was a naval battle between three thousand men, followed by an infantry battle. The "Athenians" conquered the "Syracusans" (these were the names the combatants used), made a landing on the islet and assaulted and captured a wall that had been constructed around the monument.

This might again suggest the Colosseum was flooded. The "monument" could be an altar in the center of the arena. However, Pliny the Elder mentions a bridge connected to Augustus's lake, suggesting there might have been an island there too.

The Famous Fight of Verus and Priscus

Most gladiator fights were not recorded in detail. Suetonius says they were grand, and Dio mentions both single fights and group battles. One fight, between the gladiators Verus and Priscus, was recorded by Martial:

While Priscus continued to draw out the contest, and Verus likewise, and for a long time the struggle was evenly balanced on both sides, discharge was demanded for the stout fighters with loud and frequent shouting; but Caesar obeyed his own law (the law was that once the palm had been set up the fight had to proceed until a finger was raised): he did as he was allowed, making frequent awards of plate. Still, a resolution was found for the contest, equal they fought, equal they yielded. To both Caesar awarded the wooden sword and the palm: thus courage and skill received their reward. This has happened under no emperor but you, Caesar: two men fought and two men won.

Martial's poem praises Titus, but it gives us more details than any other account of the games. It seems to suggest that a draw was unusual in gladiator fights at this level. But Titus listened to the crowd, declared the match a tie, and granted both men their freedom. This was shown by giving them a wooden sword. The usual way for a gladiator to surrender was to raise a finger (ad digitum). It's possible both men raised their fingers. Martial emphasizes Titus's fairness and generosity in letting both popular fighters live. His comment that this only happened under Titus probably refers to both being declared winners. It was expensive to train and keep gladiators, so they were not killed easily.

There is some evidence that gladiators named Priscus and Verus existed. A graveyard from the first century in Smyrna has the grave of a gladiator named Priscus. Verus's name is carved on a marble slab from Ferentinum, recording a gladiator contest. While these might not be the exact Priscus and Verus from Martial's poem, they show these names were used by gladiators.

Martial also mentions gifts being given, which Dio confirms. Dio says Titus would throw wooden balls into the crowd from his seat. These balls had descriptions of gifts, like food, clothing, slaves, animals, or gold and silver items. Anyone who caught a ball could exchange it for the gift. This was not new; Suetonius mentions that Nero did similar things, giving out many birds and other extravagant gifts.

Later Events During the Games

Suetonius also mentions other events during Titus's reign that likely happened during the opening games. Suetonius says that for one day, Titus promised to let the crowd decide the fate of the gladiators, even if it went against his own favorites. He admired the Thracian gladiators. Even though he argued passionately with the crowd about them, he stuck to his promise. He also had some informers and their managers whipped and paraded in the arena. Some were sold as slaves, and others were sent away to distant islands.

Suetonius also records that Titus invited some senators, whom he had pardoned for plotting against him, to sit with him during the games. He even let them inspect the gladiators' swords. Dio supports this, noting that Titus did not have any senators put to death during his rule.

On the last day of the games, Titus openly wept in front of the public in the Colosseum. According to Dio, Titus died the next day, after officially dedicating the amphitheatre and the baths. Suetonius says Titus left for the Sabine territories after the games but collapsed and died at the first stop.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |