Inishkea Islands facts for kids

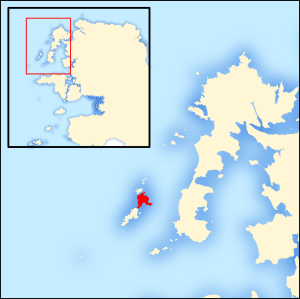

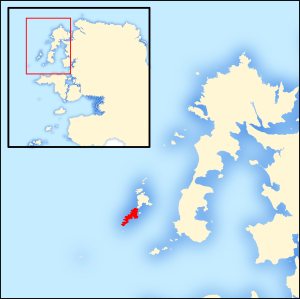

The Inishkea Islands (in Irish: Inis Cé) are a group of islands located off the coast of the Mullet peninsula in Ireland. People believe the islands are named after a saint called Saint Kea who lived there. There are two main islands: Inishkea North and Inishkea South.

In the 1800s, the islands were known for their unusual religious practices, which were different from common Christian beliefs. One special tradition involved a small clay statue of a saint, called the Godstone or Naomhog in Irish. People worshipped this statue like an idol. Because the islands were so far away from the mainland, it's thought that some very old, pre-Christian Celtic religious customs might have survived there.

In the early 1900s, more than 350 people lived on the islands. Most of them probably spoke only Irish. However, the islanders left in the 1930s after a terrible storm at sea killed many of their young men. Today, only two people live on the islands year-round, but this number grows to about fifteen during the summer months from May to September.

Contents

Island History

People have lived on the Inishkea Islands for at least 5,000 years. This means they were settled a very long time ago! The islands have many old sites from the Neolithic period, also known as the New Stone Age. These sites show us how early people lived.

There are also several ancient Christian sites on the islands. These include old churches and places where monks lived, dating from the 500s to the 900s. Similar early Christian sites can be found on other islands in the Erris area, like Duvillaun and Inishglora.

The Godstone and Old Beliefs

In 1851, an Irish Protestant named Robert Jocelyn wrote about the unusual religious practices on the islands. He noted that the islanders rarely heard about Christianity because most of them didn't speak English.

He described their worship as meeting at their chief's house and visiting a holy well called Derivla. He also mentioned a stone idol on the South Island, kept by a man named Monigan. This idol was called 'Neevougi' in Irish, which means "little saint." It looked like a thick roll of homemade cloth. People would offer new clothes to it whenever they asked for its help. An old woman, who was like its priestess, would sew these clothes onto the stone.

In 1940, English author T. H. White visited the islands. He heard stories about the "Neevougi," or Naomhóg. The islanders believed this stone could calm bad weather, help potatoes grow faster, and put out fires. However, they said a priest named Fr. O'Reilly threw it into the sea in the 1890s.

White wrote about his discoveries in his book The Godstone and the Blackymor. He learned about islanders stealing the stone from North Inishkea to South Inishkea because they were jealous of its potato-growing powers. He also described a ceremony where the stone was re-clothed in new fabric.

A famous archaeologist, Françoise Henry, visited the islands in the 1930s and 1950s. On Inishkea North, she found the ruins of St. Colmcille's Church. She also found small circular areas called Bailey Mór, Bailey Beag, and Bailey Dóite. These areas once held beehive huts used by monks in the early Christian period.

On the South Island, she found a tall cross-shaped stone and the foundations of a small church. These findings suggest that Inishkea was an important Christian center a long time ago. However, it seems that at some point, the islanders returned to older, pagan beliefs.

The 1927 Storm and Leaving the Islands

In 1927, a sudden and violent storm hit the islands at night. Many men from the islands were out fishing in their small boats called currachs. Some boats managed to get back to shore, but several did not. Ten young fishermen were lost at sea.

The island community was heartbroken by this tragedy. A few years later, most of the remaining islanders were moved to new homes, mainly on the Mullet Peninsula on the mainland. The few people who miraculously survived the storm often told the story of that terrible night. The last survivor, Pat Reilly, passed away in 2008 at the age of 101.

The Inishkea Islands have had several owners throughout history. These included the Barretts, a Norman family, and the McCormacks, who received the island from King James I. Finally, the O'Donnells of Newport took control in the 1700s. Many historians believe the islands were abandoned during the Middle Ages before people started living there again in the 1600s.

Whaling and Shellfish Industries

In 1908, a Norwegian whaling station was built on Rusheen. This is a small island very close to Inishkea South, connected to it at low tide. Whaling stations in Norway had to close due to strict environmental rules. So, many moved to other countries like Ireland, where rules were not as strict.

The whaling industry on Inishkea lasted only ten years. However, it provided jobs for many local people during tough times. The whaling station caused some arguments between the North and South islanders. It's said that all the jobs went to the South islanders, while the North islanders were left with just the bad smell from the station.

Whaling on the Inishkeas wasn't just a 20th-century thing. Sperm whales were often seen off the coast during the Middle Ages. Back then, the most important product from sperm whales was Ambergris, which is their vomit. Ambergris is very valuable because it has a sweet smell. It was sold as perfume and medicine. In the 1600s, it was traded from the coast of Connacht, through Galway, to Spain, and then to the spice markets of Cairo and Baghdad. It was said to be worth a "small fortune."

In 1946, French archaeologist Françoise Henry found evidence of a dye workshop from the 600s on Inishkea North. Monks in an early Christian monastery made purple dye from the shells of the dog whelk. This dye was very expensive and in high demand.

It would take 500 shells to get enough purple color to decorate just one letter in the famous Book of Kells. Purple was very important in early Irish laws, called Brehon Laws. Only royalty were allowed to wear purple. This tradition came from the Romans, who got it from the Greeks, who learned it from the Phoenicians.

Famine and Piracy

The people on the Inishkea Islands were also affected by the Irish Famine (1845-1847). Like most places in western Ireland, you can see the patterns of "lazy beds" on the island. These are raised rows of soil used to plant potatoes, even near the cliff edges where conditions were harsh.

However, the famine did not hit the Inishkeas as hard as the mainland. While the population on the mainland dropped a lot, it actually increased on the Inishkea islands. This is because the potato blight, a disease that destroyed potato crops, mostly stayed on the mainland. The strong winds probably helped keep the blight away from the islands. Also, the islanders had a tradition of fishing, which provided them with another source of food.

It is believed that the islanders were very active in piracy. They would attack and rob boats passing west of them. This was a highly organized operation across the whole island. They would steal cargo and share it among themselves. Wrecking, which means causing ships to crash to steal their goods, was common along the west coast.

The authorities had to send Royal Naval ships to stop this. Some islanders were even shot and killed while attacking passing vessels. Wrecking was an alternative way to make money because there were no rules or laws in these remote areas. However, when coastguards were sent to coastal sites in the late 1800s, they were disliked. They stopped wrecking and smuggling, which was bad for the islands' economy.

Geography and Current State

The Inishkea Islands are located between Inishglora to the north and Duvillaun to the south. They lie off the west coast of the Mullet peninsula. The islands help protect the mainland coast from the strong waves of the eastern Atlantic Ocean.

The islands are made of the same type of rock as the Mullet peninsula, called gneiss and schist. The Inishkeas are quite low-lying and are covered in a special type of grassy land called machair. Fine white sand is everywhere, often blown into large piles by the strong winds. This is especially true along the beach near the harbor, where sand has filled the houses of the abandoned village. The sea around the islands is incredibly clear.

The islands are not very well known outside of the local area. However, they are popular with fishermen who use the island harbor often. Regular boat trips go from Falmore on the mainland to the islands when the weather is good. The trip takes about half an hour. The boat docks at a pier right next to a pure white sandy beach, lined with small ruined cottages. Some of these cottages still have roofs and are in good condition, used by people doing work on the islands. Sand has covered the floors of most buildings, sometimes several feet deep, blown in from the beach. The island is home to donkeys and many sheep. You can now visit the island using a ferry service called the Inishkea Island Ferry, also known as Belmullet Boat Charters.

Flora and Fauna

The Inishkea Islands are home to many Atlantic grey seals. The small bays and beaches across the islands are the largest breeding grounds for grey seals in Ireland.

Seal Reproduction and Life Cycle

More than 300 seal pups are born on the islands each year. This is a big increase from the 150-180 pups born in the mid-1990s. When pups are born, they cannot go into the sea for their first ten days. There is a high death rate for young seals, with only about 50 percent of pups expected to survive their first year.

Even though seals are a protected species, some fishermen have killed them in the past. This happened because seals would bite at fish caught in nets. In the early 1980s, over 120 seals and pups were killed on the island beaches. However, their numbers have slowly recovered over the last few years.

Bird Species and Island Environment

The islands are also home to many different bird species. The geese mentioned in the island's name are barnacle geese. Other birds found on the islands include wheatears, rock pipits, and fulmars. Lapwings breed on the island, and peregrine falcons hunt for food. There is also evidence that rabbits live on the island.

The Inishkea Islands have no trees. They are made up almost entirely of machair land, with some areas of exposed rock. The islands are covered with many stone walls. These walls provide some shelter for nesting birds.