Jacqueline Cochran facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

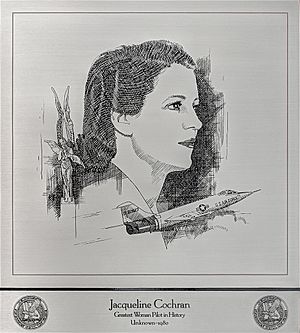

Jacqueline Cochran

|

|

|---|---|

Jacqueline Cochran c. 1943

|

|

| Born | May 11, 1906 Pensacola, Florida, U.S.

|

| Died | August 9, 1980 (aged 74) Indio, California, U.S.

|

| Occupation | aviator, test pilot, spokesperson, and businessperson |

| Spouse(s) | Jack Cochran Floyd Bostwick Odlum |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

Women Airforce Service Pilots Air Force Reserve Command |

| Years of service | 1942–1970 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal Distinguished Flying Cross |

Jacqueline Cochran (May 11, 1906 – August 9, 1980) was an amazing American pilot and a smart business leader. She was a true pioneer in women's aviation, becoming one of the most famous racing pilots of her time. Jacqueline set many flying records. She was even the first woman to break the sound barrier on May 18, 1953! During World War II, she led the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). This group had about 1,000 American women. They flew planes from factories to ports, helping the war effort without fighting.

Contents

Early Life and First Flights

Jacqueline Cochran was born Bessie Lee Pittman in Pensacola, Florida. She was the youngest of five children. Her family was not rich, but they always had food. Jacqueline worked hard from a young age.

Around 1920, when she was about 13 or 14, she married Robert Cochran. They had a son named Robert, who sadly died at age 5 in 1925. After her marriage ended, she kept the name Cochran. She also started using Jacqueline or Jackie as her first name.

Jacqueline became a hairdresser and worked in Pensacola. Later, she moved to New York City. There, she got a job at a fancy salon at Saks Fifth Avenue. Jacqueline wanted to keep her early life a secret from the public. She told people she was adopted, even though she wasn't. She also helped her family financially over the years.

Later, Jacqueline met Floyd Bostwick Odlum. He was a very rich and powerful businessman. He owned a company called Atlas Corp. and was the CEO of RKO Pictures in Hollywood. Floyd was impressed by Jacqueline. He offered to help her start her own cosmetics business.

Jacqueline started taking flying lessons in the early 1930s. She learned to fly an airplane in just three weeks! Within two years, she earned her commercial pilot's license. In 1936, she married Floyd Odlum. Floyd was very good at business and knew how to get attention. He helped Jacqueline promote her cosmetics line, which she called Wings to Beauty. She even flew her own plane around the country to sell her products!

Amazing Aviation Achievements

Jacqueline Cochran was known as "Jackie" to her friends. She was one of only three women to compete in the MacRobertson Air Race in 1934. In 1937, she was the only woman in the Bendix race. She worked with famous pilot Amelia Earhart to make sure women could join the race. That same year, Jacqueline set a new world speed record for women.

By 1938, many people thought she was the best female pilot in the United States. She had won the Bendix race. She also set new records for flying across the country and for flying at high altitudes. Jacqueline was the first woman to fly a bomber plane across the Atlantic Ocean. She won five Harmon Trophies, which are very important awards in aviation. People sometimes called her the "Speed Queen." When she passed away, no other pilot, male or female, had set more speed, distance, or altitude records than Jacqueline Cochran.

Helping Women Pilots: The Ninety-Nines

Jacqueline Cochran was a good friend of Amelia Earhart. Jacqueline became a very important member of the Ninety-Nines. This was a group for women pilots. She was their president from 1941 to 1943. She worked hard to make sure women pilots could join the Civil Air Patrol and the WASP. In her monthly messages, she encouraged members to join these groups and help with the war effort.

Flying for Britain: Air Transport Auxiliary

Before the United States joined World War II, Jacqueline helped "Wings for Britain." This group sent American-built planes to Britain. She became the first woman to fly a bomber plane, a Lockheed Hudson, across the Atlantic. In Britain, she volunteered to work for the Royal Air Force. For several months, she helped the British Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). She found skilled women pilots in the United States and brought them to England to join the ATA. Jacqueline reached the rank of Flight Captain in the ATA. This was like being a Major in the U.S. Air Force.

Leading the WASP: Women Airforce Service Pilots

In 1939, Jacqueline wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady. She suggested starting a women's flying group in the Army Air Forces. She believed that skilled women pilots could do all the non-fighting flying jobs. This would free up male pilots for combat.

In 1941, General Henry H. Arnold, the head of the Army Air Forces, asked Jacqueline to find out how many women pilots were in the U.S. He wanted to know their flying experience and if they were interested in helping the country.

General Arnold knew that women were successfully flying for the ATA in England. He asked Jacqueline to go to Britain to study how they did it. He promised that no decisions about women flying for the U.S. Army Air Forces would be made until she returned. Jacqueline asked 76 skilled female pilots to go with her to Britain to fly for the ATA. These women had a lot of flying experience, often over 1,000 hours.

While Jacqueline was in England, another women's flying group was formed in the U.S. in September 1942. It was called the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), led by Nancy Harkness Love. When Jacqueline heard about it, she quickly returned from England.

Jacqueline's time in Britain showed her that women pilots could do much more than just ferry planes. She convinced General Arnold to let women pilots have more flying opportunities. He approved the creation of the Women's Flying Training Detachment (WFTD), with Jacqueline as its leader. In August 1943, the WAFS and WFTD combined to create the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Jacqueline Cochran became the director of the WASP.

As the director, Jacqueline oversaw the training of hundreds of women pilots. This training happened at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, from August 1943 to December 1944.

Special Recognition for Service

For her important work during the war, Jacqueline received the Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) in 1945. This was a very high award for non-combat service.

Life After the War

After the war ended, Jacqueline worked for a magazine. She reported on events happening around the world. She saw the surrender of Japanese General Tomoyuki Yamashita in the Philippines. She was also the first non-Japanese woman to enter Japan after the war. She even attended the Nuremberg Trials in Germany.

On September 9, 1948, Jacqueline joined the U.S. Air Force Reserve as a lieutenant colonel. She was promoted to colonel in 1969 and retired in 1970. She was likely the first woman pilot in the U.S. Air Force. During her time in the Air Force Reserve, she earned three Distinguished Flying Cross awards for her achievements.

Setting More Flying Records

After the war, Jacqueline started flying new jet aircraft. She set many more records. She became the first woman pilot to fly faster than the speed of sound, or "go supersonic."

In 1952, Jacqueline, at 47 years old, wanted to break the world speed record for women. She borrowed a special jet plane, a Sabre 3, from the Royal Canadian Air Force. On May 18, 1953, she set a new speed record of 1,050.15 km/h (652.5 mph). With encouragement from her friend, Major Chuck Yeager, Jacqueline flew the Sabre 3 at an average speed of 652.337 mph. During this flight, the plane went supersonic. This made Jacqueline the first woman to break the sound barrier!

Jacqueline continued to set records. From August to October 1961, she set many speed, distance, and altitude records. She flew a Northrop T-38 Talon supersonic trainer. She reached amazing altitudes of over 55,000 feet (16,841 meters).

She was also the first woman to land and take off from an aircraft carrier. She was the first woman to pilot a bomber across the North Atlantic in 1941. Later, she was the first woman to fly a jet aircraft across the Atlantic. She was the first woman to make a blind (instrument) landing. Jacqueline was the only woman ever to be president of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (from 1958–1961). She was also the first pilot to fly above 20,000 feet (6,096 meters) with an oxygen mask. She was the first woman to enter the Bendix Transcontinental Race. Jacqueline Cochran still holds more distance and speed records than any other pilot, living or dead.

The Mercury 13 Program

In the 1960s, Jacqueline Cochran supported the Mercury 13 program. This was an early effort to see if women could become astronauts. Thirteen women pilots passed the same tests as the male astronauts in the Mercury program. However, the program was later canceled.

Jacqueline initially supported the program. However, some believe she later caused delays in the testing. She wrote letters to Navy and NASA officials. She expressed concerns about how the program was being run. This may have helped lead to the program's cancellation. Some think she worried she would no longer be the most famous female aviator.

In 1962, there were public hearings to decide if not including women in the astronaut program was unfair. Jacqueline Cochran herself spoke against bringing women into the space program. She said that time was important, and the U.S. needed to move forward quickly to beat the Soviets in the Space Race. At that time, NASA required astronauts to be military jet test pilots with engineering degrees. No women could meet these requirements because women were not allowed to be military jet test pilots. This ended the Mercury 13 program.

Political Life and Legacy

Jacqueline Cochran was a lifelong Republican. She became close friends with General Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1952, she and her husband helped organize a big rally to support Eisenhower running for president. Her efforts helped convince Eisenhower to run. She played a big part in his successful campaign. Eisenhower often visited Jacqueline and her husband at their ranch in California. After he left office, he even wrote parts of his memoirs there.

Jacqueline was interested in politics. In 1956, she ran for Congress in California. She won the Republican nomination, beating five male opponents. But in the main election, she lost to Dalip Singh Saund. This loss bothered her for the rest of her life.

Jacqueline Cochran passed away on August 9, 1980, at her home in Indio, California. She is buried in the Coachella Valley Public Cemetery. The local airport, which she used often, was renamed Jacqueline Cochran Regional Airport in her honor.

Jacqueline's amazing flying achievements did not always get as much attention as those of Amelia Earhart. Also, her husband's wealth meant her story wasn't seen as a "rags-to-riches" tale. Still, she is a very important figure among famous women aviators. She often used her influence to help other women in aviation.

Even without much formal education, Jacqueline was very smart. She was great at business. Her cosmetics company was very successful. In 1951, she was named one of the 25 outstanding businesswomen in America. In 1953 and 1954, the Associated Press named her "Woman of the Year in Business."

Jacqueline Cochran was also very generous. She gave a lot of her time and money to help others through charity work.

Military Awards

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Other Awards and Honors

Jacqueline Cochran received many awards from countries around the world. In 1949, France honored her for her contributions to the war and aviation. In 1951, she received the French Air Medal. She is the only woman to ever receive the Gold Medal from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. She was also elected to their board of directors.

Other honors include:

- 1964: Received the Golden Plate Award from the American Academy of Achievement.

- 1965: Inducted into the International Aerospace Hall of Fame.

- 1971: Inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

- 1985: A large crater on the planet Venus was named Cochran in her honor.

- 1992: Inducted into the Florida Women's Hall of Fame.

- 1993: Inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America.

- 1993: Inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.

- 1996: The United States Postal Service honored her with a 50¢ postage stamp. It showed her in front of a Bendix Trophy pylon with her plane.

- 2002: Inducted into the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame.

- 2006: Inducted into the Lancaster, California Aerospace Walk of Honor as its first woman.

An annual air show, the Jacqueline Cochran Air Show, is named after her. It takes place at the Jacqueline Cochran Regional Airport. Jacqueline Cochran was also the first woman to have a permanent display of her achievements at the United States Air Force Academy.

See also

In Spanish: Jacqueline Cochran para niños

In Spanish: Jacqueline Cochran para niños