Jakob Böhme facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jakob Böhme

|

|

|---|---|

Jakob Böhme (anonymous portrait)

|

|

| Born | 24 April 1575 |

| Died | 17 November 1624 Görlitz, Upper Lusatia, Lands of the Bohemian Crown, Holy Roman Empire (now split between Görlitz, Germany and Zgorzelec, Poland)

|

| Other names | Jacob Boehme, Jacob Behmen (English spellings) |

| Era | Early modern philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Christian mysticism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Boehmian theosophy The mystical being of the deity as the Ungrund ("unground", the ground without a ground) |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Jakob Böhme (born April 24, 1575 – died November 17, 1624) was a German thinker. He was a Christian mystic and a Lutheran Protestant theologian. Many people during his time thought he was a very original thinker. His first book, known as Aurora, caused a big stir. In English, his name is often spelled Jacob Boehme.

Böhme had a strong impact on later ideas like German idealism and German Romanticism. The famous philosopher Hegel even called Böhme "the first German philosopher."

Contents

Jakob Böhme's Life Story

Jakob Böhme was born on April 24, 1575, in a village called Alt Seidenberg. This village is now in Poland, near Görlitz. His father, George Wissen, was a farmer and a Lutheran. The family was quite well-off. Jakob was the fourth of five children.

His first job was looking after herds of animals. But he wasn't strong enough for farm work. So, when he was 14, he became an apprentice shoemaker in Seidenberg. His apprenticeship was tough. He lived with a family who were not Christians, which showed him the different ideas of the time.

Even without much school, Böhme prayed and read a lot. He studied the Bible and books by thinkers like Paracelsus and Weigel. After three years, he traveled as a journeyman, which means he worked in different places to improve his skills. He at least went to Görlitz.

In 1599, Böhme became a master shoemaker and opened his own shop in Görlitz. That same year, he married Katharina. They had four sons and two daughters.

Mystical Experiences

Böhme had several special spiritual experiences when he was young. The most important one happened in 1600. He was looking at a beam of sunlight reflecting in a pewter dish. He felt this vision showed him how the spiritual world worked. It also revealed the connection between God and people, and between good and evil. At first, he kept this experience to himself. He continued his work and raised his family.

In 1610, Böhme had another vision. In this one, he understood more about how everything in the universe was connected. He felt that God had given him a special purpose.

Böhme sold his shoemaking shop in Görlitz in 1613. This allowed him to buy a house in 1610, which he finished paying for in 1618. After stopping shoemaking, he sold wool gloves for a while. This meant he often visited Prague to sell his goods.

His Books and Writings

Twelve years after his vision in 1600, Böhme started writing his first book. It was called Die Morgenroete im Aufgang, which means "The Rising of Dawn." A friend later gave it the shorter name Aurora. Böhme wrote it mostly for himself and never finished it.

A handwritten copy of his unfinished book was shared with a nobleman named Karl von Ender. This nobleman made more copies and shared them around. One copy ended up with Gregorius Richter, the main pastor in Görlitz. Richter thought the book was against the church's teachings. He told Böhme he would be sent away if he kept writing.

Because of this, Böhme stopped writing for several years. But his friends, who had read Aurora, encouraged him to start again. So, in 1618, he began writing once more.

In 1619, Böhme wrote "De Tribus Principiis" (On the Three Principles of Divine Being). It took him two years to finish this second book. After that, he wrote many other essays. All his writings were copied by hand and shared only among his friends.

In 1624, Böhme's first book was officially published. It was called Weg zu Christo (The Way to Christ).

A Big Problem

The publication of The Way to Christ caused another problem. Church leaders complained, and Böhme was called to the Town Council on March 26, 1624. The Council told him:

"Jacob Boehme, the shoemaker and wild enthusiast, says he wrote his book To Eternal Life, but he didn't have it printed. A nobleman, Sigismund von Schweinitz, did that. The Council warned him to leave town; otherwise, the Prince Elector would be told. He then promised he would leave soon."

Böhme left Görlitz around May 8 or 9, 1624. He went to Dresden and stayed with a doctor for two months. In Dresden, important people and church leaders accepted him. Professors in Dresden also recognized his intelligence. They encouraged him to go back home to his family in Görlitz. While Böhme was away, his family had a hard time during the Thirty Years' War.

Once home, Böhme accepted an invitation to stay with Herr von Schweinitz. While there, Böhme started his last book, 177 Theosophic Questions. But he became very sick with a stomach problem. He had to travel home on November 7. Gregorius Richter, Böhme's main opponent from Görlitz, had died in August 1624. The new church leaders were still careful about Böhme. They made him answer many questions before he could receive a religious ceremony. He died on November 17, 1624.

In a short time, Böhme wrote many important works. These include De Signatura Rerum (The Signature of All Things) and Mysterium Magnum. He also gained followers across Europe. These followers were known as Behmenists.

Böhme's Ideas About God

Böhme's main focus in his writings was about the nature of sin, evil, and how people can be saved. Like other Lutherans, Böhme taught that humans had fallen from God's grace. This led to sin and suffering. He believed that evil forces included angels who had turned against God. God's goal, he thought, was to bring the world back to a state of grace.

However, Böhme had some ideas that were different from common Lutheran beliefs. For example, he didn't fully agree with the idea of "sola fide" (saved by faith alone). He wrote:

If someone says, I want to do good, but my human body stops me, so I can't. Still, I will be saved by God's kindness because of what Christ did. I trust in his actions and suffering; he will accept me purely by grace, without anything I do, and forgive my sins. I say such a person is like someone who knows what food is healthy but won't eat it. Instead, they eat poison, which will surely lead to sickness and death.

Another idea where Böhme might have differed was his view of the Fall (when Adam and Eve sinned). He sometimes described it as a necessary step in the universe's development. Böhme's ideas were sometimes hard to understand because he wrote in a very unique way.

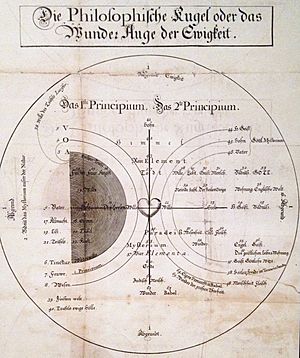

According to one expert, F. von Ingen, Böhme believed that to reach God, a person must first go through a kind of "hell." He thought God exists outside of time and space and renews himself through eternity. Böhme also talked about the trinity (God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit) but with his own special meaning. He saw God the Father as fire, who gives birth to his son, whom Böhme called light. The Holy Spirit was the living energy or divine life.

It's important to know that Böhme never said God wanted evil to happen. He believed evil was a twisting of God's original perfect order.

How the Universe Works

Böhme had a unique way of looking at the universe. He believed that for humanity to return to God, everything that was once united had to go through changes, desires, and conflicts. This included the rebellion of Satan and the separation of Eve from Adam. He thought that gaining knowledge of good and evil was part of this process.

He believed these steps were needed for creation to grow into a new, better state of harmony. This new state would be even more perfect than the first innocent state. It would allow God to understand himself in a new way by interacting with a creation that was both part of him and separate from him. For Böhme, free will was God's most important gift to humans. It allows us to choose to seek God's grace while still being unique individuals.

Views on Mary

Böhme believed that the Son of God became human through the Virgin Mary. He thought that if Mary hadn't been human, Christ would be like a stranger, not our brother. Böhme felt that Christ must grow inside us, just as he grew in Mary. Mary became blessed by accepting Christ. In a Christian who has been "reborn," like in Mary, everything temporary disappears, and only the heavenly part remains forever. Even with his special language about fire, light, and spirit, Böhme's basic ideas about Mary were similar to common Lutheran beliefs.

Who Influenced Böhme and Who He Influenced

Böhme's writings show that he was influenced by thinkers who studied Neoplatonist ideas and alchemy. Yet, his ideas stayed firmly within Christian traditions. In turn, he greatly influenced many groups that were against strict religious rules and focused on spiritual experiences. These included groups like the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and Rosicrucianism.

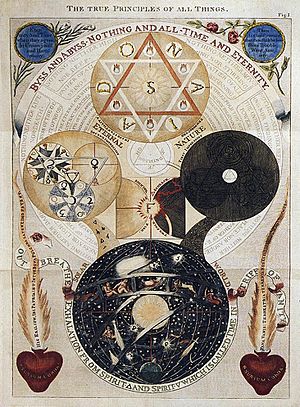

Böhme's ideas were also very important for German Romantic philosophy, especially for Schelling. The English poet and artist William Blake was also greatly influenced by Böhme's writings. Blake once said that some illustrations in Böhme's books were so good that even Michelangelo couldn't have done better.

What is Behmenism?

I do not write in the pagan manner, but in the theosophical.

Behmenism is a name for a Christian movement in Europe during the 1600s. It was based on the teachings of Jakob Böhme. People who followed Böhme's ideas usually didn't call themselves "Behmenists." This term was often used by those who disagreed with Böhme's ideas. The name "Behmen" came from a slightly changed spelling of Böhme's last name when his writings came to England in the 1640s. A follower of Böhme's ideas is called a "Behmenist."

Behmenism wasn't a single, official religious group. Instead, it described Böhme's way of understanding Christianity. Many different groups used his ideas for spiritual inspiration. Böhme's views had a big impact on many Christian mystical movements. These included the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and the Harmony Society.

Even though the name "Behmenism" comes from a changed spelling, it is still used today. It often refers specifically to English followers of Böhme's ideas. However, Böhme's influence spread across many countries.

How People Reacted to Böhme

The 1600s were a time of great change, not just in science but also in religious thought. Böhme became very important in intellectual circles in Protestant parts of Europe. This happened after his books were published in England, Holland, and Germany in the 1640s and 1650s.

Some thinkers, like Henry More, were critical of Böhme. More said Böhme wasn't a true prophet and didn't have special insights into deep philosophical questions. Overall, Böhme's writings didn't change political or religious debates much in England. But his influence could be seen in more spiritual areas, like experiments with alchemy, deep thinking about life, and spiritual meditation.

While Böhme was famous in many countries during the 1600s, his influence lessened in the 1700s. However, there was a new interest in his work later in that century. German Romantics saw Böhme as someone who prepared the way for their movement. Poets like John Milton, William Blake, and W. B. Yeats found inspiration in Böhme's writings. The German philosopher Hegel even said that Böhme was "the first German philosopher."

Jakob Böhme's Works

- Aurora: Die Morgenröte im Aufgang (unfinished) (1612)

- De Tribus Principiis (The Three Principles of the Divine Essence, 1618–1619)

- The Threefold Life of Man (1620)

- Answers to Forty Questions Concerning the Soul (1620)

- The Treatise of the Incarnations: (1620)

- I. Of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ

- II. Of the Suffering, Dying, Death and Resurrection of Christ

- III. Of the Tree of Faith

- The Great Six Points (1620)

- Of the Earthly and of the Heavenly Mystery (1620)

- Of the Last Times (1620)

- De Signatura Rerum (The Signature of All Things, 1621)

- The Four Complexions (1621)

- Of True Repentance (1622)

- Of True Resignation (1622)

- Of Regeneration (1622)

- Of Predestination (1623)

- A Short Compendium of Repentance (1623)

- The Mysterium Magnum (1623)

- A Table of the Divine Manifestation, or an Exposition of the Threefold World (1623)

- The Supersensual Life (1624)

- Of Divine Contemplation or Vision (unfinished) (1624)

- Of Christ's Testaments (1624)

- I. Baptism

- II. The Supper

- Of Illumination (1624)

- 177 Theosophic Questions, with Answers to Thirteen of Them (unfinished) (1624)

- An Epitome of the Mysterium Magnum (1624)

- The Holy Week or a Prayer Book (unfinished) (1624)

- A Table of the Three Principles (1624)

- Of the Last Judgement (lost) (1624)

- The Clavis (1624)

- Sixty-two Theosophic Epistles (1618–1624)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jakob Böhme para niños

In Spanish: Jakob Böhme para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |