Jesús Mosterín facts for kids

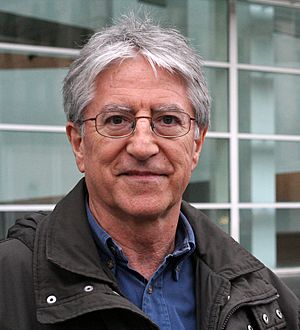

Jesús Mosterín (born September 24, 1941 – died October 4, 2017) was a very important Spanish philosopher. He was known for thinking about many different topics, often connecting science and philosophy.

Contents

About His Life

Jesús Mosterín was born in Bilbao, Spain, in 1941. He studied in Spain, Germany, and the USA. From 1983, he was a professor at the University of Barcelona, where he started a special department for logic, philosophy, and the history of science. Later, he became a research professor at the National Research Council of Spain (CSIC).

He helped bring modern logic and the philosophy of science to Spain and Latin America. Besides his university work, he also had important jobs in publishing. Mosterín cared a lot about protecting wild animals and spoke up for them in the media. He passed away on October 4, 2017, due to an illness caused by asbestos.

Logic and Thinking

Mosterín learned about logic in Germany. He wrote the first clear and modern textbooks in Spanish about logic and set theory. He studied how numbers and symbols work, showing that any kind of information, like pictures or music, can be turned into a number system. This means that all natural numbers can be seen as a giant library of all possible information!

He also helped publish the complete works of Kurt Gödel, a famous logician. Mosterín enjoyed learning about the lives of great thinkers like Gottlob Frege, Georg Cantor, Bertrand Russell, and Alan Turing. He looked at how their lives connected with their important ideas in logic.

Philosophy of Science

Understanding Scientific Ideas

Jesús Mosterín was interested in how reliable scientific theories are. He explained that science has a main part with ideas that are well-tested and proven. Around this main part is a "cloud" of new, untested ideas. As new ideas are tested and proven, they move from the "cloud" into the main part of science.

He also looked at how we "detect" and "observe" things. Detection often uses tools, like a sensor picking up a signal. Observation involves us being aware of something, sometimes with tools like glasses, but sometimes just with our senses. He also studied how we use math to create models of the real world, which helps us understand complex things.

Thinking About Biology

Mosterín joined in discussions about how living things change over time (evolution) and how genetics work. He also asked a very simple but deep question: What is life? He looked at different ideas about what makes something alive, like needing to eat, reproduce, or evolve. He found that none of these ideas fully explained life.

He thought that our understanding of biology is mostly about life on Earth. We don't know if life elsewhere in the universe would be the same. He also explored how we think about living things and different species.

Understanding the Universe

Mosterín was fascinated by how our scientific view of the universe fits into a sensible way of looking at the world. He studied how reliable our theories about the universe are.

He looked closely at the idea of "cosmic inflation," which is a theory about how the universe expanded very quickly after the Big Bang. He and another philosopher, John Earman, concluded that even though this idea is popular, there wasn't enough strong proof to fully accept it as a main part of science yet. Mosterín also showed that the "anthropic principle," which suggests the universe is the way it is so that humans can exist, doesn't really explain anything new.

Practical Philosophy

How We Make Good Choices

Jesús Mosterín thought about how we make smart decisions. He said that being rational means using a good strategy to think and act.

- Theoretical rationality is about what we believe. It means our ideas should make sense (be logical) and be supported by facts.

- Practical rationality is about how we live our lives. It means making choices that help us reach our most important goals and preferences. It's about living the best possible life.

Ethics, Animals, and Rights

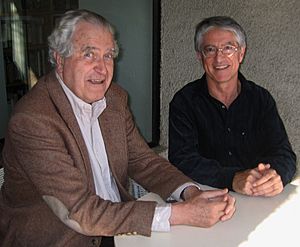

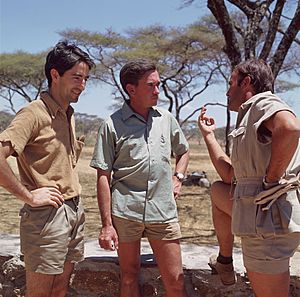

Mosterín cared deeply about animals. He worked with Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente, a famous Spanish naturalist, to help people appreciate nature. He was strongly against cruel activities like bullfighting. He played a big part in getting bullfights banned in Catalonia, Spain, in 2010. He wrote books explaining why bullfighting is wrong.

As the honorary president of the Spanish Great Ape Project, he worked with Peter Singer to argue for basic legal rights for great apes (like chimpanzees and gorillas). While he believed we should never be cruel to animals, he also thought we need to be realistic about using animals for research or food. He pushed for strict rules to ensure animals are treated well. He suggested stopping painful experiments and ending "factory farming" where animals are kept in tiny spaces. He even thought that in the future, meat could be grown in labs!

Mosterín believed that our natural ability to feel compassion for others, combined with knowledge and empathy, is the best reason to treat animals kindly.

Thinking About Politics

Mosterín looked at modern liberal democracy, which tries to balance freedom and democracy. He pointed out that freedom is about doing what you want, while democracy is about doing what most others want. He believed that the more freedom we have, the better, as long as it doesn't lead to violence.

He thought that things like the Internet offer a better model for freedom than old ideas like the nation-state. He dreamed of a world without nation-states, where smaller local areas work together with strong global organizations. This, he felt, would allow freedom to truly grow.

Understanding Humans

What Makes Us Human

In recent times, thinkers like Jesús Mosterín have brought back the idea of "human nature." With new discoveries about our genes (the human genome) and how our brains work, this idea has become very important again.

Mosterín believed that our human nature is the information passed down through our genes. Your own unique nature is in your own genes. He explained that our genes show the history of humans. The oldest parts of our genes are about basic life functions, common to all living things. Newer parts of our genes are about things that make us unique, like walking on two legs, having big brains, and using language. He helped explain how to tell the difference between what's natural (from our genes) and what's cultural (learned from society) in human behavior.

What is Human Culture

Mosterín also developed new ideas about what culture is, where it comes from, and how it changes. He said that human nature is information, and so is human culture. But they are passed on differently: nature is passed through genes, while culture is learned from others and stored in our brains.

He believed that only individuals have culture, stored as connections in their long-term memory. When we talk about "collective cultures," it's really about many individual cultures. He studied how culture changes, especially with the rise of the Internet. He thought that keeping the Internet free and efficient is super important for the future of human culture.

History of Ideas

Jesús Mosterín admired Bertrand Russell's book on the history of Western philosophy. Mosterín took on a huge project himself: writing a universal history of thought. This wasn't just about Western ideas, but also Asian and even very old "Archaic" ideas. His series of books, Historia del Pensamiento (History of Thought), looks at philosophy, science, and ideas from different cultures. He wrote clearly and critically, digging into arguments to find their strengths and weaknesses.

Some of his books covered ancient Mesopotamia, where he looked at ideas from old texts. He also wrote about Aristotle, not just as a philosopher but also as a scientist. His book on India included discussions about language, math, and different philosophical schools like Buddhism.

His most recent books in the series focused on the three main monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He saw the Jewish tradition as the source for the others. He wrote about important Jewish thinkers like Maimonides and Spinoza. His book on Christians was the largest. He discussed how Christianity developed, looking at key thinkers like Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, and big historical events like the Crusades. For Islam, he described the creation of the Quran and the history of Muslim law, philosophy, and science, highlighting thinkers like Avicenna and Averroes.

See also

In Spanish: Jesús Mosterín para niños

In Spanish: Jesús Mosterín para niños

- List of animal rights advocates

Works

- El triunfo de la compasión: Nuestra relación con los otros animales [Triumph of Compassion: Our Relation with the other Animals]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2014. 354 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-8465-9.

- Ciencia, filosofía y racionalidad [Science, Philosophy and Rationality]. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial, 2013. 358 pp. ISBN: 978-84-9784-776-6.

- El reino de los animales [The Kingdom of Animals]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2013. 403 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-7450-6.

- El islam: Historia del pensamiento [History of Islamic Thought]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2012. 403 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-6991-5.

- Epistemología y racionalidad [Epistemology and Rationality], 3rd edition. Lima: Fondo Editorial UIGV, 2011. 376 pp. ISBN: 978-612-4050-16-9.

- A favor de los toros [In Favor of Bulls]. Pamplona: Editorial Laetoli, 2010. 120 pp. ISBN: 978-84-92422-23-4.

- Diccionario de Lógica y Filosofía de la Ciencia [Dictionary of Logic and Philosophy of Science] (coauthored with Roberto Torretti), 2nd edition. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2010. 690 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-8299-0.

- Naturaleza, vida y cultura [Nature, Life and Culture]. Lima: Fondo Editorial UIGV, 2010. 160 pp. ISBN: 978-612-4050-12-1.

- Los cristianos: Historia del pensamiento [History of Christian Thought]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2010. 554 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-4979-5

- La cultura humana [Human Culture]. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 2009. 404 pp. ISBN: 978-84-670-3085-3.

- La cultura de la libertad [The Culture of Freedom]. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 2008. 304 pp. ISBN: 978-84670-2697-9.

- Lo mejor posible: Racionalidad y acción humana [The best possible: Rationality and Human Action]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2008. 318 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-8206-8.

- La naturaleza humana [Human Nature], 2nd edition, Austral series. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 2008. ISBN: 978-84-670-2813-3.

- Los lógicos [The Logicians], 2nd edition, Austral series. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 2007. 418 pp. ISBN: 978-84-670-2507-1.

- Helenismo: Historia del pensamiento [History of Hellenistic Thought]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2007. ISBN: 978-84-206-6187-2.

- India: Historia del pensamiento [History of Indian Thought]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2007. 260 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-6188-9.

- China: Historia del pensamiento [History of Chinese Thought]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2007. 282 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-6187-2.

- Kurt Gödel, Obras completas [Complete Works], 2nd enlarged edition. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2006. 470 pp. ISBN: 84-206-4773-X.

- Ciencia viva: Reflexiones sobre la aventura intelectual de nuestro tiempo [Living Science: Reflections on the Intellectual Adventure of Our Time], 2nd enlarged edition. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 2006. 386 pp. ISBN: 84-670-2355-4.

- Crisis de los paradigmas en el siglo XXI [Crisis of 21st Century Paradigms]. Copublished by University Inca Garcilaso and University Enrique Guzmán. Lima, 2006. ISBN: 9972-888-38-X.

- La naturaleza humana [Human Nature]. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 2006. 418 pp. ISBN: 84-670-2035-0.

- El pensamiento arcaico [History of Archaic Thought]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2006. 285 pp. ISBN: 84-206-5833-2.

- La Hélade [History of Greek Thought]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2006. 292 pp. ISBN: 84-206-5833-2.

- Aristóteles [Aristotle]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2006. 378 pp. ISBN: 978-84-206-5836-0.

- Los judíos [History of Jewish Thought] . Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2006. 305 pp. ISBN: 84-206-5837-5.

- Diccionario de Lógica y Filosofía de la Ciencia [Dictionary of Logic and Philosophy of Science] (coauthored with Roberto Torretti). Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2002. 670 pp. ISBN: 84-206-3000-4.

- Teoría de la Escritura [Theory of Writing], 2nd edition. Icaria Editorial. Barcelona 2002. 384 pp. ISBN: 84-7426-199-6.

- Filosofía y ciencias [Philosophy and Science]. Lima: Fondo Editorial UIGV y Editorial de la Universidad P. A. Orrego, 2002. 156 pp. ISBN: 9972-888-04-5.

- Ciencia viva: Reflexiones sobre la aventura intelectual de nuestro tiempo [Living Science: Reflections on the Intellectual Adventure of Our Time]. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 2001. 382 pp. ISBN: 84-239-9765-0.

- Conceptos y teorías en la ciencia [Concepts and Theories in Science], 3rd, enlarged edition. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2000. 318 pp. ISBN: 84-206-6741-2.

- [Original edition of] Rudolf Carnap, Untersuchungen zur allgemeinen Axiomatik [Investigations on the general theory of axiomatic systems], coedited with Thomas Bonk. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2000. 166 pp. ISBN: 3-534-14298-5.

- Los Lógicos [The Logicians]. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 2000. 324 pp. ISBN: 84-239-9755-3.

- ¡Vivan los animales! [Long Live to the Animals!]. Madrid: Editorial Debate, 1998. 391 pp. ISBN: 84-8306-141-4.

- Los derechos de los animales [Animals’ Rights]. Madrid: Editorial Debate, 1995. 111 pp. ISBN: 84-7444-857-3.

- El pensamiento de la India [Indian Thought]. Barcelona: Salvat Editores, 1982. 65 pp. ISBN: 84-345-7864-6.

- Ortografía fonémica del español [Phonemic Spelling for Spanish]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1981. 205 pp. ISBN: 84-206-2303-2.

- Un cálculo deductivo para la lógica de segundo orden [Deductive Calculus for Second Order Logic]. Valencia: Cuadernos Teorema, 1979. 52 pp. ISBN: 84-370-0100-5.

- Racionalidad y acción humana [Rationality and Human Action]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1978, 1987. 199 pp. y 218 pp. ISBN: 84-206-2223-0.

- Teoría axiomática de conjuntos [Axiomatic Set Theory]. Barcelona: Ariel, 1971, 1980. 141 pp. ISBN: 84-344-1003-6.

- Lógica de primer orden [First-order Logic]. Barcelona: Ariel, 1970, 1976, 1983. 141 pp. ISBN: 84-344-1003-6.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |