Joanna Baillie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joanna Baillie

|

|

|---|---|

c. 1825 drawing of Joanna Baillie by Mary Ann Knight

|

|

| Born | 11 September 1762 Bothwell (Kingdom of Great Britain) |

| Died | 23 February 1851 Hampstead |

| Occupation | Writer, tragedy writer |

Joanna Baillie (born September 11, 1762 – died February 23, 1851) was a famous Scottish poet and playwright. She was best known for her series of plays called Plays on the Passions (published between 1798 and 1812). She also wrote Fugitive Verses in 1840.

Joanna Baillie was interested in how people think and feel, and also in Gothic stories (which are often dark and mysterious). During her lifetime, many people praised her work. She lived in Hampstead, England, and became friends with other well-known writers like Anna Barbauld and Walter Scott. She lived to be 88 years old.

Contents

Joanna Baillie's Early Life

Family Background

Joanna Baillie was born in Bothwell, Scotland, on September 11, 1762. Her mother, Dorothea Hunter, was the sister of two famous Scottish doctors, William and John Hunter. Her father, Rev. James Baillie, was a minister and later a professor at the University of Glasgow. Her aunt, Anne Home Hunter, was also a poet.

Joanna was the youngest of three children. Her twin sister died as a baby. Her older sister, Agnes Baillie, lived to be 100 years old! Their brother, Matthew, became a doctor in London.

Childhood and Education

Joanna was not a serious student when she was very young. She loved the Scottish countryside and had her own pony. She enjoyed making up plays and telling stories. Her parents were strict and didn't encourage her to show strong emotions. She only saw one puppet show as a child, never a real play.

In 1769, her family moved to Hamilton. Her father became a minister there. Joanna didn't learn to read until she was ten years old. She then went to a boarding school in Glasgow. It was said that the school helped "transform healthy little hoydens into perfect little ladies."

Joanna had a big moment when she first saw a theatre play. After that, she started writing plays and poems. She also showed talent in math, music, and art.

Moving to London

Joanna's father died in 1778, and the family's money situation became harder. Her brother Matthew went to study medicine at Balliol College, Oxford. The rest of the family moved to Long Calderwood.

In 1784, they moved back to London. This happened after her uncle, Dr. William Hunter, died and left his house and art collection to her brother. This collection later became the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow.

Through her aunt, Anne Home Hunter, Joanna met other important literary women of the time. These included Fanny Burney and Elizabeth Montagu. Joanna studied plays by famous writers like Corneille, Racine, Molière, Voltaire, and Shakespeare. She wrote her own plays and poems while helping to run her brother's house.

Her first works were published anonymously (without her name) in 1790. Joanna, her sister, and her mother moved several times. They finally settled in Colchester, where Joanna started writing her Plays on the Passions.

In 1802, they moved to Hampstead, where Joanna lived with her sister Agnes for the next 50 years. Neither sister ever married. In 1800, a new printing of her work revealed her identity. Her aunt Anne then introduced her to London's literary society.

Later Life and Friendships

Joanna's mother died in 1806. Her neighbors, Anna Laetitia Barbauld and her niece Lucy Aikin, became close friends. Joanna also wrote many letters to Sir Walter Scott, and they often visited each other. Scott even wrote an introduction for her play The Family Legend in 1810.

When Joanna was in her seventies, she was sick for a year. But she got better and kept writing and sending letters. In her eighties, she included Scottish folk songs in her Fugitive Verses (1840).

Joanna wanted all her works to be put into one book. She saw this "great monster book," as she called it, published in 1851, shortly before she died. She remained healthy until the end. She died in Hampstead in 1851, almost 90 years old. Her sister Agnes lived to be 100. Both sisters were buried with their mother in Hampstead. In 1899, a tall memorial was built for Joanna Baillie in the churchyard where she was born in Bothwell.

Joanna Baillie's Writings

Poetry Collections

- 1790 Her first book was Poems: Wherein it is Attempted to Describe Certain Views of Nature and of Rustic Manners. She later updated some of these poems for her Fugitive Verses (1840). Her poem "Winter Day" described the sights and sounds of winter.

- 1821 Her Metrical Legends of Exalted Characters told heroic stories in verse. These included tales of William Wallace, Christopher Columbus, and Lady Grizel Baillie. She was inspired by the popular ballads of Walter Scott.

- 1840 With encouragement from her friend, the poet Samuel Rogers, Baillie released Fugitive Verses. This collection included both old and new poems. Many people believed her Scottish songs would be remembered for a long time.

Famous Plays

Joanna Baillie is most famous for her plays. She had a unique idea to write plays that focused on one main human emotion, or "passion," in each play.

- 1798 The first volume of Plays on the Passions was published without her name. It included Count Basil (about love), The Tryal (a comedy about love), and De Monfort (about hatred).

- In a long introduction, she explained her plan to show the deepest human feelings. She wanted to show "genuine and true to nature" emotions. This new idea caused a lot of talk. Everyone in London wondered who the author was. People thought it was a man until someone noticed that many main characters were middle-aged women. Joanna finally said she was the author in 1800.

- 1800 Her play De Monfort was performed in London. Famous actors John Kemble and Sarah Siddons starred in it. The play ran for eight nights but wasn't a big hit.

- 1802 The second volume of Plays on the Passions was published with Joanna Baillie's name on it. It included The Election (a comedy about hatred), Ethwald (a tragedy about ambition), and The Second Marriage (a comedy about ambition).

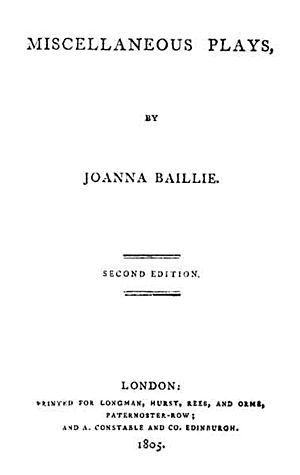

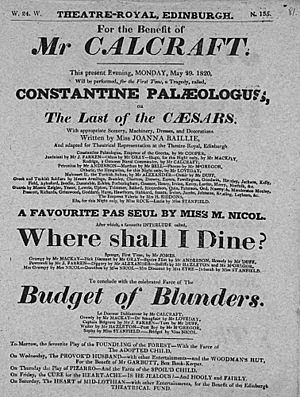

- 1804 She published Miscellaneous Plays, which included the tragedies Rayner and Constantine Paleologus, and a comedy, The Country Inn.

- 1810 Her Scottish play, The Family Legend, was performed in Edinburgh. Sir Walter Scott supported it, and it was very successful for a short time. Scott wrote the introduction for this play.

- 1812 The third and last volume of Plays on the Passions came out. It had two Gothic tragedies, Orra and The Dream, a comedy called The Siege, and a musical play, The Beacon. The tragedies and comedy were about the feeling of Fear, and the musical play was about Hope.

- 1836 Three more volumes of Miscellaneous Plays were published. They included nine new plays and finished her Plays on the Passions series. Critics were very excited about these new plays.

Besides her plays, Joanna Baillie also wrote beautiful poems and songs. Some of her best-known poems are Lines to Agnes Baillie on her Birthday, The Kitten, and To a Child. She also adapted some Scottish songs. Her plays also contained lively and beautiful songs, like The Chough and The Crow. Her poem A Mother to her Waking Infant was praised for showing real observations of babies and mothers.

Her Views on Plays

Joanna Baillie was at first shy about publishing her work. She once wrote to Sir Walter Scott that she would only publish a book of poetry because her brother wanted her to. She wrote for enjoyment, not for fame.

However, in 1804, she wrote an introduction to her Miscellaneous Plays. In it, she defended her plays as being good for the stage. She was annoyed by critics who said she didn't understand how plays worked on stage. She believed her plays were unfairly called "closet drama" (plays meant only for reading, not performing). She thought this was partly because she was a woman.

She also pointed out that theatres in her time used big stages and grand shows. She argued that her plays, which focused on small details of human feelings, would work best in smaller, well-lit theatres where actors' faces could be seen clearly. She wanted her plays to be acted, not just read. She hoped some of her plays would "continue to be acted even in our canvas theatres and barns."

Helping Others and Her Legacy

Charity and Advice

Joanna Baillie was financially secure, so she often gave half of her earnings from writing to charity. She was involved in many good causes. In the 1820s, she supported efforts to help chimney sweeps. She believed that a simple plan in prose was better than a poem for serious issues.

She also used her knowledge of the literary world to help other writers. Authors who were struggling, women writers, and working-class poets often asked her for help. She wrote letters, used her contacts, and gave advice to less well-known writers. In 1823, she put together a collection of poems by famous writers to help an old school friend who was a widow with daughters to support.

Her Reputation

Many people admired Joanna Baillie. The American writer John Neal called her the "female Shakespeare of a later age." John Stuart Mill remembered her play Constantine Paleologus as "one of the most glorious of human compositions."

Some of her songs were set to music by famous composers. Beethoven even set her poem "O Swiftly Glides the Bonny Boat" to music in 1815.

Not everyone liked her work at first. Francis Jeffrey wrote a very critical review of her Plays on the Passions in 1803. He attacked her ideas about plays. Even though he praised her "genius," Baillie saw him as a literary enemy. They didn't meet until 1820, but then they became good friends.

Maria Edgeworth, another writer, visited Baillie in 1818. She said that Joanna and her sister had "agreeable and new conversation." They didn't just talk about old literature or gossip.

Joanna Baillie offered a new way of looking at drama and poetry. Many writers of her time thought she was one of the best women poets, second only to Sappho (an ancient Greek poet). Harriet Martineau said Baillie "enjoyed a fame almost without parallel." Her works were translated into other languages and performed in the United States and Britain.

However, her fame faded in the 19th and 20th centuries. Her plays were not performed much. But in the late 20th century, critics began to see how her deep understanding of the human mind influenced Romantic literature. Today, scholars recognize her importance as a creative playwright and a thinker about drama. They also see her as a key woman writer of the Romantic period.

Friendships with Other Writers

Joanna Baillie was good friends with Lady Byron. This friendship also led her to become close with Lord Byron. Lord Byron even tried to get one of her plays performed in London, but it didn't happen. Their friendship continued until Lord and Lady Byron had problems in their marriage. Baillie sided with her friend Lady Byron. After this, Baillie became more critical of Lord Byron's work.

One of the people Baillie wrote to most was Sir Walter Scott. They exchanged so many letters that they could fill a large book! Scott respected and supported Baillie as a writer. But their friendship was more than just professional; their letters show personal details and talks about their families.

On September 11, 2018, Google celebrated Joanna Baillie's 256th birthday with a special Google Doodle. Her work has recently become popular again as people recognize her important contributions.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |