John Marrant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids John Marrant |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | May 15, 1785 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 15, 1755 New York City, New York |

| Died | April 15, 1791 (aged 35) Islington, London, England |

| Nationality | American |

| Denomination | Huntingdonian church |

| Spouse | Elizabeth (Herries) Marrant |

| Occupation | Minister, missionary |

| Education | Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion |

John Marrant (born June 15, 1755 – died April 15, 1791) was an American preacher and missionary. He was one of the first black preachers in North America. John was born free in New York City. As a child, he moved with his family to Charleston, South Carolina.

His father died when John was young. He and his mother also lived in Florida and Georgia. John later escaped and lived with the Cherokee people for two years. During the American Revolutionary War, he supported the British. After the war, he moved to London, England. There, he joined the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion and became a preacher.

In 1785, Marrant traveled to Nova Scotia as a missionary. He started a Methodist church in Birchtown. He got married there before moving to Boston, Massachusetts. In 1790, he went back to London. John Marrant wrote a book about his life called A Narrative of the Lord's Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant, a black. He also published a sermon and a journal.

Contents

Early Life and Travels

John Marrant was born free in New York City on June 15, 1755. He was the second youngest of five children. His father passed away in 1759 when John was four years old.

His mother moved the family to St. Augustine, Florida. John started school there, which was special for black children at that time. After about 18 months, during the Seven Years' War, his family moved to Georgia. Georgia was a British colony then. He went to school until he was 11, learning to read and write.

Later, they moved to Charleston, South Carolina. John became very interested in music. He learned to play the French horn and the violin. He often played music for important people at parties. He studied music for about two years. After that, he worked as an apprentice carpenter for over a year.

His Spiritual Journey

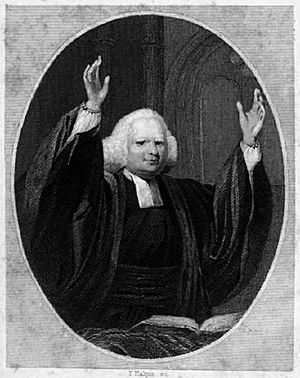

When John was 13, around 1768, he and a friend went to hear a Methodist preacher named George Whitefield. Whitefield was very active in the South during a time called the Great Awakening. John had a powerful experience during the sermon. He fell to the floor and couldn't move or speak for a while. He was carried home.

Doctors were called, but John refused medicine. He felt better by reading the Bible. His family worried about his strong focus on religion. They thought he was acting strangely. After arguments with his family about his faith, he left home. He walked into a forest outside the city, trusting God to take care of him.

A Cherokee hunter found him. The hunter knew John's family but John convinced him not to take him back to town. John traveled and hunted with the Cherokee for over two months. They gathered animal furs to trade. When they reached the hunter's fortified Cherokee town, John was stopped. He was told he had no good reason to be there and was sentenced to death.

John prayed to Jesus. His prayers seemed to change the mind of the person who was supposed to carry out the sentence. This person argued with the judge and arranged for John to meet the king. The king spared John's life. Everyone heard him pray in both English and Cherokee.

John lived with the Cherokee for two years. During this time, he visited other tribes like the Catawa, Housaw, and Creek people. He helped many Native Americans become Christians. It is believed he helped create strong ties between black people and the Cherokee.

He wore clothes made from animal skins, like the Native Americans. He didn't wear pants but had a sash around his middle and a long piece of cloth down his back. When he returned to Charleston, his family didn't recognize him at first. John was very happy when his sister finally knew who he was. He wrote in his journal, "thus the dead was brought to life again; thus the lost was found." His story reminded people of Lazarus and Joseph from the Bible. These stories were important to black Christians who were enslaved or captured, as they hoped for freedom.

John looked for work as a free carpenter on plantations. He also did missionary work, sharing Christianity with enslaved people. Some owners didn't like it, but others allowed their enslaved people to become Christians. This continued until the American Revolution began.

Serving During the American Revolution

During the American Revolutionary War, John Marrant was forced to join the Royal Navy. This was called impressment. He served as a musician for over six years before leaving the Navy in 1782. In 1780, he was at the Siege of Charleston. One year later, he was hurt in the Battle of Dogger Bank. He wrote about battles in his book, but official Navy records don't show him serving.

During the war, enslaved black people were told they would gain their freedom if they served the British. About 3,000 people agreed to this. They were called Black Loyalists. In 1783, they were taken to Nova Scotia. Their names were written down in the Book of Negroes. These Black Loyalists were very interested in learning about Christianity. John's brother sent him a letter asking him to come to Nova Scotia.

His Ministry Work

After leaving the Navy, John Marrant worked for a clothing merchant in London. In London, he met Reverend Whitehead and told him about his powerful religious experience. Reverend Whitehead introduced John to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. She encouraged him to become a minister.

John joined the ministry of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion. This was a Christian group that combined ideas from Calvinism and Methodism. It separated from the Church of England in 1783. John was ordained as a preacher on May 15, 1785, in Bath. After that, he left for Nova Scotia. He arrived in November 1785, after an eleven-week journey from England.

He lived in Birchtown, Nova Scotia, which was the largest new black community. There, he started a Huntingdonian church. John Marrant served the black people in the Birchtown area and helped build a strong Christian community. He traveled throughout Nova Scotia to other towns where Black Loyalists had settled, like Jordan River and Cape Negro. He also spoke to white church groups and First Nation people, including the Miꞌkmaqs.

When he gave sermons, he used Bible verses to suggest he was a prophet sent to Nova Scotia. He said he was there to help the Black Loyalists who listened to him. He also warned that those who didn't listen would face problems. These messages sometimes worried white residents. He spoke about the difficulties black people faced, saying that God's lessons were often hidden. He said, "God often hides the sensible signs of his favor from his dearest friends… real Christians, whilst they are among fiery serpents are awaiting with desire, and holy expectations, for the good of the promise."

He had some trouble with other churches, especially other Methodist churches. White ministers were upset when their church members went to Marrant's services. But he inspired many black communities to grow in their Christian faith. He influenced religious leaders like Boston King, John Ball, and Moses Wilkinson, who were Methodists. Another was David George, a Baptist.

John didn't receive all the money he expected from the Countess for his missionary work. He also got smallpox and was sick for six months. In 1787, Marrant traveled to Boston, Massachusetts. The next year, he became the chaplain of the African Masonic Lodge in Boston. This group was active in the movement to end slavery in the United States. This was one of the first American groups to use the word "African" in its name. It showed the growing identity of people of African descent in the United States after the Revolution. In a speech at the Lodge in 1789, Marrant described black people as a "distinct nation" within the Christian family of mankind.

His Writings

In 1785, with help from Reverend William Aldridge, John Marrant published his book, A Narrative of the Lord's Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant, A Black. William Aldridge wrote down John's story as he told it. The book described his time living with the Cherokee people. It became a very popular story of its kind. It also told about his journey to Christianity and his observations of black people's lives during the Colonial period.

His struggle as a black Christian in an irreligious, white, slave-owning world that made little distinction between slaves and freeborn blacks was intended to inspire not just people of his own colour but his white readers as well.

—James W. St. G. Walker

Experts have noticed that his book has a different feel from his later writings. Scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. has suggested that many early African-American stories were written down by white editors. These editors sometimes changed the style of the stories.

In 1789, Marrant gave a sermon called A Sermon Preached on the 24th Day of June 1789...at the Request of the Right Worshipful the Grand Master Prince Hall, and the Rest of the Brethren of the African Lodge of the Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons in Boston. In it, he spoke about the equality of all people before God. This sermon was also published. His last published work was a journal from 1790, called A Journal of the Rev. John Marrant, from August the 18th, 1785, to the 16th of March, 1790.

Personal Life and Legacy

John Marrant married Elizabeth Herries on August 15, 1788, in Birchtown, Nova Scotia. Her parents were Black Loyalists. He and Elizabeth returned to Boston. In a letter to Marrant, Margaret Blucke (the wife of Stephen Blucke) asked about Marrant's children. It's possible he was married before or adopted children. A boy also traveled with him, but his name isn't in the Journal. He might have been Anthony Elliot from Birchtown, who was an assistant.

Marrant traveled to London in 1789 or 1790. His journal from the previous five years was published there. He preached in churches in London, including the Whitechapel area. He died on April 15, 1791, in Islington and was buried at the chapel graveyard on Church Street.

John Marrant did not live a long life, but he had a big impact on black people in the United States and Canada. This included the Black Loyalists who settled in Sierra Leone in Africa in 1792. He inspired future generations through his writings. He shared a message of never giving up and having faith.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |