Mi'kmaq facts for kids

| Lnu | |

|---|---|

Grand Council Flag of the Miꞌkmaq Nation. Although the flag is meant to be displayed hanging vertically as shown here, it is quite commonly flown horizontally, with the star near the upper hoist.

|

|

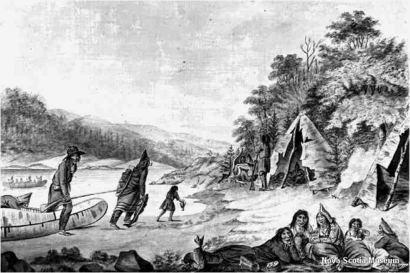

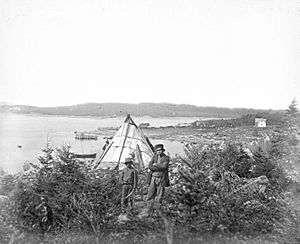

A Miꞌkmaw father and child at Tufts Cove, Nova Scotia, around 1871

|

|

| Total population | |

| 66,748 registered members (2023) 168,480 claimed Mi'kmaq ancestry (2016) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| (Mi'kma'ki, Dawnland) Canada, United States |

|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 28,282 |

| Nova Scotia | 18,814 |

| New Brunswick | 9,025 |

| Quebec | 7,655 |

| Maine | 1,489 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1,483 |

| Languages | |

| English, Miꞌkmaq, French | |

| Religion | |

| Native American religion, Christianity, others | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Algonquian peoples Especially Abenaki, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot |

|

| Person | Lnu |

|---|---|

| People | Lnu'k (Mi'kmaq) |

| Language | Mi'kmawi'simk |

| Country | Mi'kma'ki Wabanaki |

The Mi'kmaq (also Mi'gmaq, Lnu, Miꞌkmaw or Miꞌgmaw; MIG-mah;) are a First Nations people. They are native to the Northeastern Woodlands of North America. Their traditional lands are mainly in Canada's Atlantic Provinces. This includes Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. They also live in the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec and parts of Maine in the United States. Their traditional territory is called Miꞌkmaꞌki.

As of 2023, there are about 66,748 registered Mi'kmaq people. This number includes members of the Qalipu First Nation in Newfoundland. The Mi'kmaq language is an Eastern Algonquian language. In 2021, about 9,245 people said they speak Mi'kmaq. The language was once written using hieroglyphs. Today, it is mostly written using the Latin alphabet.

The Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Pasamaquoddy nations signed important agreements. These were called the Covenant Chain of Peace and Friendship Treaties. They signed them with the British Crown in the 1700s. The Miꞌkmaq believe they never gave up their land or rights through these treaties. In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada agreed. They said the 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty was still valid. This treaty promised Indigenous Peoples the right to hunt, fish, and trade on their lands.

The Miꞌkmaw Grand Council is an important governing body. It works with the Canadian federal and Nova Scotia provincial governments. This partnership started with a special agreement on August 30, 2010. It was the first agreement of its kind in Canadian history. It included all First Nations in Nova Scotia.

Historically, the Grand Council, called Santé Mawiómi, was the main government for the Miꞌkmaw people. It was made up of chiefs from different districts of Miꞌkmaꞌki. The 1876 Indian Act changed this. It made First Nations set up elected governments like the Canadian system. It tried to limit the Grand Council's role to spiritual guidance.

Contents

Miꞌkmaq Grand Council: Santé Mawiómi

On August 30, 2010, the Miꞌkmaw Nation and Nova Scotia made a special agreement. It confirmed that the Miꞌkmaw Grand Council is the official group that talks with the Canadian and Nova Scotia governments. This agreement came from the Miꞌkmaq–Nova Scotia–Canada Tripartite Forum. It was the first time all First Nations in a province worked together like this in Canada.

The Santé Mawiómi, or Grand Council, was the traditional government for the Miꞌkmaw people. It included chiefs from different districts of Miꞌkmaꞌki. The 1876 Indian Act changed this system. It made First Nations create elected governments. It tried to make the Council only a spiritual guide.

The Grand Council also included Keptinaq (district chiefs). There were also elders and putús, who read wampum belts and kept historical records. They also handled treaties with non-Native people and other tribes. A women's council was also part of it. The grand chief was a title given to one of the district chiefs. This title was usually passed down in a family.

In 1610, Grand Chief Membertou became a Catholic. He made an alliance with the French Jesuits. The Miꞌkmaq traded with the French. They allowed some French settlements on their land.

Gabriel Sylliboy (1874 – 1964) was a respected Mi'kmaq leader. He was elected Grand Chief of the Council in 1918. He was re-elected many times and held this position for his whole life.

In 1927, Chief Sylliboy was charged for hunting muskrat pelts out of season. He was the first to use the rights from the Treaty of 1752 in his court defense. He lost his case at that time. In 1985, the Supreme Court of Canada finally recognized the 1752 treaty rights. This ruling in R. v. Simon protected Indigenous hunting and fishing. In 2017, Nova Scotia officially pardoned Chief Sylliboy. This was 50 years after his death. His grandson, Andrew Denny, said his grandfather was a respected leader.

The Grand Council traditionally met on a small island called Mniku. This island is on the Bras d'Or lake in Cape Breton. Today, this site is part of the Chapel Island reserve, also known as Potlotek. The Grand Council still meets at Mniku to talk about important issues for the Miꞌkmaq Nation.

Taqamkuk (Newfoundland) was once part of Unamaꞌkik territory. Later, it became a separate district in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Miꞌkmaq Language

In 2021, about 9,245 people said they speak the Miꞌkmaq language. For 4,910 of them, it was their mother tongue. For 2,595, it was the language they spoke most often at home.

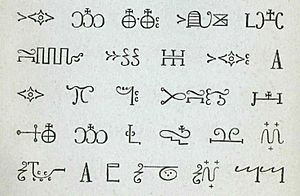

Hieroglyphic Writing

The Mi'kmaq language was once written using Miꞌkmaq hieroglyphic writing. This system was developed in 1677 by a French missionary named Chrestien Le Clerq. He saw Mi'kmaq children using marks to remember prayers. Today, the language is mostly written using letters from the Latin alphabet.

At the Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site, you can find petroglyphs. These are ancient carvings on rocks. They show "life-ways of the Mi'kmaq." They include hieroglyphics, human figures, houses, decorations, boats, and animals. These carvings were made by the Mi'kmaq, who have lived there for a very long time. The petroglyphs date from ancient times up to the 1800s.

Jerry Lonecloud (1854 – 1930) was a Mi'kmaq elder. He is known as the "ethnographer of the Mi'kmaq nation." In 1912, he copied some of the Kejimkujik petroglyphs. He gave his work to the Nova Scotia Museum. He also wrote the first Mi'kmaq memoir, based on his spoken stories.

Christian Kauder was a missionary in Miꞌkmaꞌki from 1856 to 1871. He included Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing in his German book in 1866. This included prayers like the Holy Mary Rosary prayer.

David L. Schmidt and Murdena Marshall published a book in 1995. It showed prayers and stories written in hieroglyphs. They said these hieroglyphs were a full writing system. They believe it is the oldest writing system for an Indigenous language in North America (north of Mexico).

Meaning of the Word Miꞌkmaq

By the 1980s, the spelling Miꞌkmaq became widely used. It is preferred by the Miꞌkmaq people themselves. It replaced the older spelling Micmac. The Miꞌkmaq feel the spelling "Micmac" is connected to colonialism. The "q" ending is for the plural form of the noun. Miꞌkmaw is the singular form and is also used as an adjective, like "the Miꞌkmaw nation."

The Miꞌkmaq use different spellings for their language. These include Miꞌkmaq in Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland. In New Brunswick, they use Miigmaq. In Quebec, the Listuguj Council uses Miꞌgmaq. Some literature uses Mìgmaq.

Lnu is the word the Miꞌkmaq use for themselves. It means "human being" or "the people." Historically, they called themselves Lnu. They used níkmaq (my kin) as a greeting.

The French first called the Miꞌkmaq Souriquois. Later, they called them Gaspesiens. The British first called them Tarrantines.

There are different ideas about where the name Miꞌkmaq comes from. The Miꞌkmaw Resource Guide says it means "the family." The Anishinaabe people call the Miꞌkmaq Miijimaa(g), meaning "The Brother(s)/Ally(ies)."

Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye was the first European to write down the term "Mi'kmaq" in 1676. Some believe "Mi'kmaq" comes from the Mi'kmaq word megamingo (earth). This suggests they might have been called "the Red Earth People."

Miꞌkmaq Geography

Miꞌkmaw Country, known as Miꞌkmaꞌki, has traditionally been divided into seven districts. Before the Indian Act, each district had its own government and borders. Each district had a chief and a council. The council included band chiefs, elders, and other community leaders. The district council made laws, handled justice, divided fishing and hunting areas, and made peace or war.

Miꞌkmaq Districts

The eight Miꞌkmaw districts are:

- Epekwitk aq Piktuk (Prince Edward Island and Pictou)

- Eskikewaꞌkik

- Kespek (Gespeꞌgewaꞌgi) (Gaspé)

- Kespukwitk

- Siknikt

- Sipekniꞌkatik

- Ktaqmkuk (Gtaqamg) (Newfoundland)

- Unamaꞌkik (Unamaꞌgi) (Cape Breton)

Working with Governments

Tripartite Forum

In 1997, the Miꞌkmaq–Nova Scotia–Canada Tripartite Forum was created. On August 31, 2010, the governments of Canada and Nova Scotia signed a historic agreement with the Miꞌkmaw Nation. This agreement means the federal government must talk with the Miꞌkmaw Grand Council. They must do this before starting any projects that affect the Miꞌkmaq in Nova Scotia. This was the first agreement of its kind in Canada. It included all First Nations in an entire province.

Marshall Decision

On September 17, 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada made an important ruling. It supported the treaty rights of Miꞌkmaw Donald Marshall Jr.. The ruling said Mi'kmaq people have a treaty right to hunt, fish, and gather for a "moderate livelihood." This means they can make a living from the land and water resources. This right was based on the Treaty of 1752.

After this decision, there were some conflicts. In Miramichi Bay, Mi'kmaq fishers started laying lobster traps out of season. Some non-Mi'kmaq fishers destroyed Mi'kmaq traps and equipment. This led to events like the Burnt Church Crisis. The National Film Board made a documentary about it called Is the Crown at war with us?. It showed how officials seemed to act against Mi'kmaq fishers.

To help resolve the conflict, the government offered to buy commercial fishing licenses. This was to help expand the Mi'kmaq lobster fishery. By 2007, the government had spent $160 million on this plan.

In 2020, a new dispute arose. Mi'kmaq fishers in Nova Scotia started their own self-regulated lobster fishery. They said this was part of their treaty right to a moderate livelihood. However, existing rules prevent them from selling their lobster to non-Mi'kmaq buyers. Mi'kmaq fishers say these rules don't match the Marshall decision.

In 2021, a group of Miꞌkmaq First Nations bought Clearwater Seafoods. This was a huge investment in the seafood industry. It means that the Mi'kmaq now own a large part of the fishing business in the region.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

In 2005, Miꞌkmaw activist Nora Bernard led a large class-action lawsuit. It was for survivors of the Canadian Indian residential school system. The Government of Canada paid over $5 billion to settle the lawsuit.

In 2011, the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission visited Atlantic Canada. They heard stories from survivors of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School. This was the only residential school in the region.

Miꞌkmaq Kinaꞌ matnewey (Education)

The first Miꞌkmaq-run school in Nova Scotia, Miꞌkmaq Kinaꞌ matnewey, opened in 1982. This school is considered a very successful First Nation Education Program in Canada.

By 1997, Miꞌkmaq communities on reserves were in charge of their own education. By 2014, Nova Scotia had 11 band-run schools. The province has a high rate of Indigenous students staying in school. More than half of the teachers in these schools are Miꞌkmaq. Between 2011 and 2012, there was a 25% increase in Miꞌkmaw students going to university.

Miꞌkmaq History

Before European Contact

In southwestern Nova Scotia, there is proof that people have used the land for at least 4,000 years. Kejimkujik National Park has canoe routes used by Indigenous people for thousands of years. Some Mi’kmaq traditions say they came from the west. They lived alongside another group called the Kwēdĕchk. After a long war, the Mi’kmaq became the main people in the area.

Mi'kmaq elder Roger Lewis studied how Mi'kmaq people lived before Europeans arrived. They had a close relationship with nature. They fished, hunted, and gathered food. Their settlements were chosen based on these activities.

Archaeologists believe the Miꞌkmaq developed their own culture in their territory. They focused on living by the sea. Before contact with Europeans, Mi'kmaq lived in small groups. They moved with the seasons to find food. In winter, they stayed in inland camps. In summer, they moved to the coast.

They fished for smelt, herring, and cod. They gathered waterfowl eggs and hunted geese. The coast offered shellfish and relief from insects. In autumn, they harvested American eels. Smaller groups would then go inland to hunt moose and caribou. Moose was very important. They used its meat for food, skin for clothing, and bones for tools. They also hunted deer, bear, rabbit, beaver, and porcupine.

Early European fishermen started visiting the Mi'kmaq lands around 1520. They set up camps to dry fish. Trading furs for European goods changed Miꞌkmaw life. Men spent more time trapping animals like beaver. This made them more aware of their hunting territories. More Mi'kmaq gathered in summer trading spots. This led to larger groups led by skilled traders.

The Nova Scotia Museum says that bear teeth and claws were used for decorations. Women used porcupine quills to decorate clothing and moccasins. The main hunting weapon was the bow and arrow, made from maple wood. The Miꞌkmaq ate many kinds of fish, shellfish, and eels. They also hunted marine mammals like porpoises and seals.

Miꞌkmaw territory was the first part of North America that Europeans used for resources. Explorers like John Cabot and Jacques Cartier reported on the area. This encouraged fishermen and whalers from Portugal, Spain, France, and England to visit. By 1578, many European ships were in the Saint Lawrence area. Many were interested in the fur trade.

17th and 18th Centuries

Colonial Wars

The Miꞌkmaq joined the Wapnáki (Wabanaki Confederacy). This was an alliance with four other Algonquian-speaking nations. These included the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet. The Wabanaki Confederacy was allied with the Acadian people.

For 75 years, the Miꞌkmaq and Acadians fought to keep the British from taking over their land. This included six wars, like the French and Indian Wars. France lost control of Acadia in 1710. They also gave up their claim to most of the land in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht.

However, the Miꞌkmaq were not part of this treaty. They never gave their land to the British. In 1715, the British claimed Miꞌkmaq territory. The Miꞌkmaq complained to the French. They said the French king could not give away land he did not own. The French said that by European laws, land not owned by Christians could be claimed by any Christian prince. Miꞌkmaw historian Daniel Paul noted that this idea was unfair. He also pointed out that Grand Chief Membertou became Christian in 1610. This would have made Mi'kmaq land exempt even by those old laws.

The Miꞌkmaq and Acadians used military force to resist British settlements. They raided towns like Halifax and Dartmouth. During the French and Indian War, the Miꞌkmaq helped the Acadians resist the British Expulsion. Their resistance weakened after the French lost at the Siege of Louisbourg (1758). In 1763, Great Britain officially took control of all of Miꞌkmaki in the Treaty of Paris.

Peace and Friendship Treaties

Between 1725 and 1779, the Mi'kmaq, Wolastoqey (Maliseet), and Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) signed many treaties. These were called the Covenant Chain of Peace and Friendship Treaties. They created a peaceful relationship with the British Crown. The Mi'kmaq say they never gave up their land or rights through these treaties. The Supreme Court of Canada agreed with this in the R v Marshall case.

Some historians say the first treaty in 1725 did not give up hunting, fishing, and gathering rights. The Halifax Treaties (1760–61) ended the fighting between the Miꞌkmaq and the British.

The 1752 Peace and Friendship Treaty was signed by Jean-Baptiste Cope for the Shubenacadie Miꞌkmaq. This treaty was important in the Supreme Court of Canada's 1985 decision in R. v. Simon.

The treaties of 1760-61 mention Miꞌkmaw submission to the British. However, later Miꞌkmaw statements show they wanted a friendly and equal relationship. In the early 1760s, there were about 300 Miꞌkmaw fighters and thousands of British soldiers. The Miꞌkmaw negotiators wanted peace, fair trade, and friendship with the British. In return, the Mi'kmaq offered friendship and allowed some British settlement. They did not formally give up land. They expected that any new British settlements would be negotiated and involve gifts to the Mi'kmaq. The agreements did not set clear limits on British expansion. But they promised the Mi'kmaq access to their natural resources.

More British settlers, like the New England Planters and United Empire Loyalists, arrived. This put pressure on the land and the treaties. The Miꞌkmaq tried to enforce the treaties. At the start of the American Revolution, many Miꞌkmaw and Maliseet tribes supported the Americans. They fought in the Battle of Fort Cumberland in 1776. Miꞌkmaw delegates signed the Treaty of Watertown with the United States in 1776.

As their military power decreased in the 1800s, the Miꞌkmaq asked the British to honor the treaties. They reminded them of their duty to give "presents" for occupying Miꞌkmaꞌki. The British offered "relief" instead. They told the Miꞌkmaq to give up their way of life and become farmers. They also said Mi'kmaq children should go to British schools.

Gabriel Sylliboy was the first Miꞌkmaw elected grand chief in 1919. He was also the first to fight for treaty recognition in court. He fought for the Treaty of 1752 in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia.

In 1986, the first Treaty Day was celebrated in Nova Scotia. This day, October 1, honors the treaties between the British and the Miꞌkmaw people. The treaties were officially recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1982.

19th Century

Royal Acadian School

Walter Bromley was a British officer who lived in Halifax from 1813 to 1825. He helped establish the Royal Acadian School. He supported the Miꞌkmaq people. He worked to improve their lives through settlement, farming, and education. He also studied their languages.

Mi'kmaq Missionary Society

Silas Tertius Rand helped start the Mi'kmaq Missionary Society in 1849. He lived in Hantsport, Nova Scotia, from 1853 until his death in 1889. He traveled among Miꞌkmaw communities, sharing the Christian faith. He learned the language and recorded Miꞌkmaw oral traditions. Rand translated parts of the Bible into Miꞌkmaq and Maliseet. He also created a Miꞌkmaq dictionary and collected many legends. Through his work, he introduced the stories of Glooscap to a wider audience.

Mi'kmaq Hockey Sticks

The Miꞌkmaq have played ice hockey for a long time. Records show them playing as early as the 1700s. Since the 1800s, the Miꞌkmaq have been known for inventing the ice hockey stick. The oldest known hockey stick was made by Miꞌkmaq people between 1852 and 1856. It was carved from hornbeam wood.

In 1863, the Starr Manufacturing Company in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, started selling "Mic-Mac" hockey sticks. These sticks became very popular across Canada and internationally. By the early 1900s, the Mic-Mac hockey stick was the best-selling stick in Canada. Making hockey sticks was a main job for Miꞌkmaq people on reserves in Nova Scotia. The Miꞌkmaq continued to make hockey sticks until the 1930s, when factories took over the production.

==Images for kids

-

Grand Chief Jacques-Pierre Peminuit Paul (3rd from left with beard) meets Governor General of Canada, Marquess of Lorne, Red Chamber, Province House, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1879.

20th and 21st Centuries

Jerry Lonecloud worked with historian Harry Piers to record the history and culture of the Miꞌkmaw people. Lonecloud wrote the first Miꞌkmaw memoir.

World Wars

In 1914, over 150 Miꞌkmaw men joined the military during World War I. From Lennox Island First Nation, 34 out of 64 men enlisted. They fought bravely, especially in the Battle of Amiens. In 1939, over 250 Miꞌkmaq volunteered for World War II. More than 60 Miꞌkmaq also served in the Korean War in 1950.

Miꞌkmaq of Newfoundland

When Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, the political leader, Joey Smallwood, said there were "no Indians in Newfoundland." This meant the Miꞌkmaq people of Newfoundland did not get official recognition as First Nations.

In 1972, activists formed the Native Association of Newfoundland and Labrador. This group represented the Mi'kmaq, Innu, and Inuit peoples. Later, it became the Federation of Newfoundland Indians (FNI). The FNI included six Mi'kmaq bands.

In 1987, the Miawpukek Mi'kmaq First Nation was officially recognized. Their community of Conne River became reserved land for the Mi'kmaq.

Recognizing the other Mi'kmaq in Newfoundland took much longer. In 2011, the Government of Canada officially recognized the Qalipu First Nation. This new band does not have its own reserved land. By 2012, over 25,000 people had applied to join the Qalipu. In total, over 100,000 applications were sent in.

In 2017, about 18,044 people were eligible for Band membership. In 2018, the Qalipu First Nation updated its list to 18,575 members. In 2019, the Miꞌkmaq Grand Council accepted the Qalipu First Nation. By 2021, nearly 24,000 people were recognized as founding members.

Miꞌkmaq Religion, Spirituality, and Tradition

Current Forms of Miꞌkmaw Faith

Some Miꞌkmaw people practice the Catholic faith. Others follow traditional Miꞌkmaw beliefs. Many have adopted both because they find the two systems can work together.

Oral Traditions in Miꞌkmaw Culture

The Miꞌkmaw people mostly passed down their traditions through spoken stories. They used petroglyphs, but these were not common. It is believed that before Europeans arrived, the Miꞌkmaq did not have a written language. Storytelling was very important.

There were three main types of oral traditions: religious myths, legends, and folklore. This included Miꞌkmaw creation stories. These stories explained how the world and society were organized. For example, they told how men and women were created. Good storytellers were highly valued. They shared important lessons and provided entertainment.

One myth tells that the Miꞌkmaq believed evil among people caused them to fight. This made the creator-sun-god sad. He cried tears that caused a great flood. Only an old man and woman survived to repopulate the earth.

Spiritual Sites

One important spiritual place for the Miꞌkmaq Nation is Mniku. This is where the Miꞌkmaw Grand Council, or Santé Mawiómi, gathers. It is on Chapel Island in Bras d'Or Lake in Nova Scotia. The island is also home to the St. Anne Mission. This is an important pilgrimage site for the Miꞌkmaq. The island has been declared a historic site.

Ethnobotany (Plants and Their Uses)

The Abies balsamea (balsam fir) tree is traditionally used by the Miꞌkmaq in many ways. They use its buds, cones, and inner bark for health issues like diarrhea. The gum is used for burns, colds, and wounds. The boughs are used to make beds. The bark is used to make a drink. The wood is used for fires.

Miꞌkmaq First Nation Communities

Miꞌkmaw names in the table below are spelled using different systems. The Smith-Francis spelling is the most recent. It is used across Nova Scotia and in most Miꞌkmaw communities.

Miꞌkmaq Population

| Year | Population | Verification |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 4,500 | Estimation |

| 1600 | 3,000 | Estimation |

| 1700 | 2,000 | Estimation |

| 1750 | 3,000 | Estimation |

| 1800 | 3,100 | Estimation |

| 1900 | 4,000 | Census |

| 1940 | 5,000 | Census |

| 1960 | 6,000 | Census |

| 1972 | 10,000 | Census |

| 1998 | 15,000 | SIL |

| 2006 | 20,000 | Census |

| 2021 | 66,748 | Census |

Before Europeans arrived, the Miꞌkmaw population was estimated to be between 3,000 and 30,000. In 1616, a missionary named Father Biard thought there were over 3,000 Miꞌkmaq. But he noted that many had died in the 1500s due to European diseases. Diseases like Smallpox, wars, and alcohol caused the population to drop even more. It reached its lowest point in the mid-1600s. After that, the numbers slowly grew again. The population became stable in the 1800s. In the 1900s, the population started to rise significantly.

Commemorations

The Miꞌkmaw people are honored in many ways. These include the ship HMCS Mi'kmaq (R10). Also, places like Lake Mi'kmaq and the Mic Mac Mall are named after them.

Notable Miꞌkmaq People

Academics

- Pamela Palmater, professor at Toronto Metropolitan University

- Marie Battiste, professor at the University of Saskatchewan

Activists

- Anna Mae Aquash, activist (1946–1976)

- Donald Marshall, Jr., fought for Mi'kmaq fishing rights

- Daniel N. Paul, Elder, author, historian, and human rights activist

- Gabriel Sylliboy, Grand Chief of the Miꞌkmaq Nation, 1918 to 1964

Artists

- Rita Joe, poet

- Ursula Johnson, visual artist

- Nikki Gould, actress, Degrassi: Next Class

- Bretten Hannam, screenwriter and film director

- Amanda Peters, writer

- Morgan Toney, folk singer-songwriter and fiddler

- Jeff Barnaby, film director and screenwriter

Athletes

- Patti Catalano, marathon runner

- Jahkeele Marshall-Rutty, soccer player

- Sandy McCarthy, played for the Calgary Flames ice hockey team

- Everett Sanipass, played for the Quebec Nordiques ice hockey team and the Chicago Blackhawks NHL team.

Military

- Étienne Bâtard (18th century)

- Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope

- Sam Gloade

- Paul Laurent

Other Notable People

- Judge Timothy Gabriel, first Miꞌkmaw judge in Nova Scotia

- Elsie Charles Basque, first Mi'kmaw to earn a teaching certificate and recipient of the Order of Canada

- Henri Membertou, Grand Chief and spiritual leader (c. 1525-1611)

- Lawrence Paul, a chief of Millbrook First Nation

- Brian Francis, Senator of Canada

Maps

Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

-

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket

-

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

See also

In Spanish: Micmac para niños

In Spanish: Micmac para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |