John Rankin (abolitionist) facts for kids

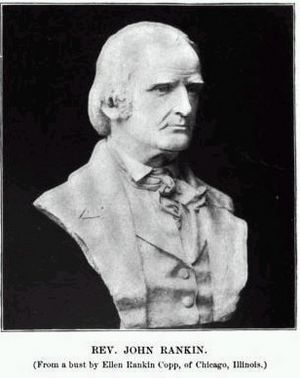

John Rankin (born February 5, 1793 – died March 18, 1886) was an American Christian minister, teacher, and a strong opponent of slavery. When he moved to Ripley, Ohio, in 1822, he became known as one of Ohio's first and most active "conductors" on the Underground Railroad. This was a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Famous anti-slavery leaders like William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Dwight Weld, Henry Ward Beecher, and Harriet Beecher Stowe were inspired by Rankin's writings and his work against slavery.

After the American Civil War ended, Henry Ward Beecher was asked, "Who ended slavery?" He replied, "Reverend John Rankin and his sons did."

Contents

Who Was John Rankin?

Early Life and Strong Beliefs

John Rankin was born in Dandridge, Tennessee. His parents, Richard and Jane Rankin, were very religious and strict. They were also able to read and write, which was unusual for people in their remote area. His mother, Jane, strongly disliked slavery.

From the age of eight, two major events shaped John's life and faith. One was a big religious movement called the Second Great Awakening. The other was a planned slave uprising led by Gabriel Prosser in 1800.

John went to a school with log walls and an earthen floor. He later attended Washington College Academy, led by Rev. Samuel Doak, who also opposed slavery. John graduated in 1816. After college, he became a minister in Tennessee. However, his anti-slavery views were not welcome there. He left Tennessee in 1817 and never returned.

Even though he wasn't a natural public speaker, Rankin worked hard to give good sermons. Within a few months, he bravely spoke out against "all forms of unfair treatment," especially slavery. He helped start the Tennessee Manumission Society in 1815, which worked to free enslaved people. His church leaders told him to leave Tennessee if he kept speaking against slavery from the pulpit. Knowing his faith wouldn't let him stay silent, he decided in 1817 to move his family to Ripley, Ohio. This was a free state across the Ohio River, where he heard many anti-slavery people had settled.

On his journey north, Rankin preached in Kentucky. He learned that a church in Carlisle, Kentucky, needed a minister. This church had been involved in anti-slavery work since 1807. Rankin stayed there for four years and even started a school for enslaved people. However, angry mobs forced the school to close. Because of money problems in the area, Rankin decided to finish his family's journey to Ripley. On the night of December 31, 1821, he rowed his family across the icy river. In Ripley, he started a school for boys. The famous Ulysses S. Grant once attended this school in 1838.

A New Home in Ohio

In 1822, Ripley was a rough town with many saloons. When the Rankins first arrived, people often bothered the new preacher. They would follow him and gather outside his cabin while his permanent home was being built. This first home was very close to the river. When the local newspaper started printing his letters about slavery, Rankin became well-known to both supporters and opponents of the anti-slavery movement. Slave owners often came to his door, demanding information about people who had escaped. Rankin soon realized his home was too easy for people to reach, making it hard to raise his family safely.

In 1829, Rankin moved his wife and nine children (they would eventually have thirteen) to a house on top of a 540-foot-high hill. This new home offered a wide view of the village, the Ohio River, and the Kentucky shoreline. It also had farmland and fruit trees for income. One of his sons, Adam Lowry Rankin, later founded a church in California.

The Underground Railroad and His House

Stories say that a lantern or candle was placed in the front window of the Rankin home to guide runaway slaves from across the Ohio River in Kentucky. However, stories from formerly enslaved people suggest a pole with a light was used, which would have been easier to see from the river. From their hilltop home, the family could raise a lantern on a flagpole to signal to enslaved people in Kentucky when it was safe to cross into Ohio. Rankin also built a staircase up the hill for those escaping to climb to safety.

For over 40 years before the Civil War, many enslaved people who escaped to freedom through Ripley stayed at the Rankin family's home. Rankin himself said, "I have had under my roof as many as twelve fugitive slaves at a time, all of whom made good their way to Canada." Sometimes, entire families stayed there. This home became known as the Rankin House and is now a US National Historic Landmark.

The Real Eliza's Story

During a visit by Rankin to Lane Seminary, he told Professor Calvin Stowe a powerful story. In 1838, the Rankins had helped a woman who escaped by crossing the frozen Ohio River with her child in her arms. Stowe's wife, Harriet Beecher Stowe, also heard this story. She later used this woman's experience to create the character Eliza in her famous book, Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Film Depiction

Brothers of the Borderland is a film that shows Rankin's work with the Underground Railroad in Ripley. It is shown permanently at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

His Powerful Book: Letters on Slavery

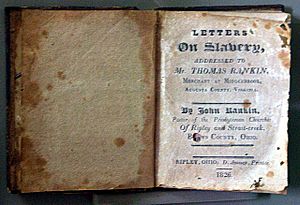

Early in his time in Ripley, Rankin learned that his brother Thomas, a merchant in Virginia, had bought enslaved people. This made him write a series of anti-slavery letters to his brother. These letters were published by the local Ripley newspaper, The Castigator. When the letters were put together into a book in 1826, called Letters on Slavery, they became one of the first clear anti-slavery books printed west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Thomas Rankin was convinced by his brother's words. He moved to Ohio in 1827 and freed the people he had enslaved. By the 1830s, Letters on Slavery was widely read by people who wanted to end slavery across the United States. In 1832, William Lloyd Garrison printed them in his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. Garrison later called Rankin his "anti-slavery father," saying that Rankin's book was why he joined the fight against slavery.

Fighting for Freedom Beyond the Church

In 1833, Rankin met Theodore Dwight Weld when they both helped create the American Anti-Slavery Society. Weld came from Connecticut to attend Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio. Rankin attended important discussions about slavery organized by Weld in 1834 and wrote a pamphlet about the problems caused by slavery.

In November 1834, Weld began a year-long series of speeches throughout Ohio at Rankin's church. These speeches helped raise awareness of the anti-slavery movement in the state. At Weld's urging, Rankin also started giving similar speeches. Many local anti-slavery groups were formed.

In April 1835, the Ohio Anti-slavery Society was created. Both Rankin and Weld played key roles at its first meeting in Zanesville, Ohio.

Facing Danger for His Beliefs

On his way home from that meeting, Rankin faced his first real mob attack. People threw rotten eggs at him. When he stopped in Chillicothe, Ohio, to speak at a church, stones were thrown through a window.

In 1836, Weld invited Rankin to join a group called "the Seventy." This group was chosen by the American Anti-Slavery Society to travel to churches across the Northern states. Their goal was to preach for the immediate end of slavery and to form local anti-slavery groups. Rankin's church allowed him to take a year off to join this effort. His passion for the cause grew even stronger as people opposed his "dangerous" views. Some people, even those against slavery, feared causing a slave uprising.

A reward of up to $3,000 was offered for Rankin's capture. In 1841, he and his sons had to fight off attackers who came to burn his house and barn in the middle of the night.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it illegal to help runaway enslaved people, even in free states. This law made the danger and importance of their work even greater. However, at an anti-slavery meeting, Rankin declared that "Disobedience to the enactment is obedience to God." This meant he believed obeying God was more important than obeying an unfair law.

Disagreements within his own church, caused by Rankin trying to remove church members who owned slaves, led him to resign in 1846. He had been a minister at the Ripley Presbyterian Church for 24 years. More than a third of the church members left with him. They helped Rankin start what became the Free Presbyterian Church. This new church may have had as many as 72 congregations before the Civil War. After the war, Rankin was happy when the Presbyterian churches in Ripley reunited.

Remembering John Rankin

"Freedom's Heroes" Monument

In May 1892, six years after John Rankin's death, a monument called "Freedom's Heroes" was dedicated to Rankin and his wife, Jean Lowry Rankin. It stands in the Maplewood Cemetery in Ripley, Ohio.

National Abolition Hall of Fame

In 2013, John Rankin was honored by being added to the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum in Peterboro, New York.

Writings

- Rankin, John (1836). An address to the churches in relation to slavery : delivered at the first anniversary of the Ohio State Anti-slavery Society. Medina, Ohio: Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.

Archival material

Old papers and records about Rankin are kept by the Ohio History Connection in Columbus.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |