José Gaspar facts for kids

José Gaspar, also known as Gasparilla, was a legendary Spanish pirate. People say he lived from about 1756 to 1821. He supposedly sailed the Gulf of Mexico from his secret base in southwest Florida. This was during Florida's second Spanish period (1783-1821).

Stories say Gaspar was the "Last of the Buccaneers". He was a very active pirate who collected a huge treasure. He took many ships and held many people for ransom. The legends say he died by jumping from his ship to avoid being caught by the U.S. Navy. His treasure is supposedly still hidden.

Even though Gaspar is a popular character in Florida stories, there is no real proof he ever existed. No old records, ship logs, newspapers, or other documents mention him. Also, no pirate items linked to him have been found where he supposedly had his "pirate kingdom." The first time José Gaspar was written about was in a brochure from the early 1900s for the Gasparilla Inn on Gasparilla Island. The person who wrote it even said the exciting story was made up and had "not a true fact in it." Later stories about Gaspar are based on this made-up account. He was even accidentally put into a 1923 book about real pirates, which has caused confusion ever since.

José Gaspar's legend is celebrated in Tampa, Florida every year during the Gasparilla Pirate Festival. This festival first started in 1904.

Contents

The Legend of José Gaspar

The story of José Gaspar's life changes a bit depending on who tells it. Most stories agree he was born in Spain around 1756. They say he joined the Spanish Navy but then became a pirate around 1783. He supposedly died in southwest Florida during a battle with the United States Navy in late 1821. However, the details of his life are very different in various tales.

How Gaspar Became a Pirate

Some stories say Gaspar started poor in Spain. He kidnapped a girl for money. When caught, he chose to join the navy instead of going to prison. He served well for years. Then, he led a mutiny against a bad captain. He stole a ship and sailed to Florida.

Other versions say Gaspar was a Spanish nobleman. He became a high-ranking officer in the Spanish Royal Navy. He was even an advisor to King Charles III of Spain. But he supposedly angered a lady who then made false accusations against him. Some say she claimed he stole the crown jewels. To avoid arrest, he took a ship and escaped. He promised to get revenge on his country.

Still other tales say Gaspar was a very smart Spanish admiral. He supposedly did steal the crown jewels. When his crime was found out, he took the "best ship of the Spanish fleet" with loyal followers. He left his wife and children to sail across the Atlantic Ocean.

Gaspar's Pirate Life

In all versions, Gaspar settled on the quiet southwest coast of Spanish Florida around 1783. He became a pirate on his ship, the Floriblanca. Gaspar set up his base on Gasparilla Island. Soon, he was feared across the Gulf of Mexico. He took many ships and gathered a huge treasure. This happened during the second Spanish rule of Florida. Most male prisoners had to join his crew or be killed. Women were taken to a nearby island, called Captiva Island for this reason. They were held for ransom or became wives for the pirates.

Different stories tell different adventures of Gaspar. One famous tale involves a Spanish (or Mexican) princess named Useppa. She was on a captured ship. She refused Gaspar, and he killed her in anger. Gaspar immediately regretted it. He took her body to a nearby island, which he named Useppa in her honor. He buried her himself. Some stories say this lady was Josefa de Mayorga, daughter of a viceroy of New Spain. They claim the island's name changed over time. But there is no proof for this.

Similarly, Sanibel Island is said to be named by Gaspar's first mate, Rodrigo Lopez. He named it after his lover back in Spain. Gaspar supposedly let Lopez go home. Some legends claim Gaspar gave Lopez his personal diary. This diary is said to be a source of information about the pirate, but it has never been found.

Gaspar is also linked to other pirates, both real and legendary. Some stories say he worked with the real pirate Pierre Lafitte. They claim Lafitte barely escaped the battle where Gaspar died. This is unlikely, as Lafitte was not known to be in southwest Florida. He also died in Mexico before Gaspar's supposed end. Gaspar has also been linked to Henri Caesar and "Old King John." These are other legendary pirates with little historical proof.

The End of Gaspar

Most stories agree that José Gaspar died in late 1821. This was soon after Spain gave control of the Florida Territory to the United States. Gaspar had decided to stop being a pirate after almost 40 years. He and his crew gathered on Gasparilla Island to share their huge treasure.

While they were dividing the treasure, a lookout saw what looked like an easy target: a British merchant ship. Gaspar couldn't resist taking one last prize. He led his crew onto the Floriblanca to chase the ship. But when the pirates fired a warning shot, their target raised an American flag. It was not a merchant ship. It was the United States Navy pirate-hunting schooner USS Enterprise in disguise.

A fierce battle began. The Floriblanca was hit many times below the water and started to sink. Instead of giving up, Gaspar supposedly wrapped an anchor chain around his waist. He leaped from the front of the ship, shouting, "Gasparilla dies by his own hand, not the enemy's!" He plunged into the Gulf of Mexico, close to shore. Most of his surviving crew were caught and hanged. A few escaped or were put in prison. Some stories claim one of the escapees was John Gómez, who would tell the tale to later generations.

Was José Gaspar Real?

Even though his story has been told many times since 1900, there is no proof that the pirate José Gaspar ever lived.

Historical Clues

The time Gaspar supposedly lived was after the "Golden Age of Piracy" (around 1650-1725). That's when real pirates like Blackbeard were active. European countries worked hard to stop piracy in the early 1700s. By 1730, most major pirates were gone.

Some pirate attacks still happened when Gaspar supposedly arrived in Florida in the 1780s. But the navies of Britain, France, Spain, and the new United States were actively patrolling the waters. It would have been very hard for any pirate to attack ships for decades on the huge scale Gaspar's stories claim. The original Gasparilla story says he had about $30 million in stolen treasure by 1821. To compare, Spain sold the entire Florida territory to the United States that same year for $5 million.

There is little evidence that pirates ever based their operations in southwest Florida. Real pirates mostly stole easy-to-sell goods like food, tobacco, and wood from small merchant ships. They didn't usually get huge amounts of gold from big Spanish ships. There were no towns on Florida's west coast to sell stolen goods until much later. So, the area was sometimes a hiding place for outlaws, but not a good base for active pirates.

Checking Old Records

Historians have tried to find records proving Gaspar existed, but they haven't found any. The original story claims he stole Spain's "crown jewels" and the "prized vessel" of the Spanish fleet. But research in Spanish records shows no mention of Gaspar in the royal court, his navy career, or his crimes.

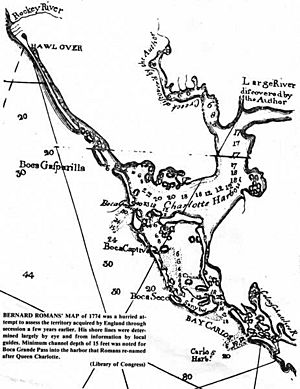

Even though he was supposedly the most feared pirate in the Gulf of Mexico for decades, searches of old American newspapers found no mention of "Gaspar" or "Gasparilla." No pirate ship called Floriblanca is mentioned either. The U.S. Navy archives have no record of Gaspar in ship logs or court records of piracy trials. The USS Enterprise was in the West Indies Squadron to stop piracy. But it was in Cuba in December 1821, not in Charlotte Harbor, where Gaspar's last battle supposedly happened.

Local Place Names

There is no proof that several local place names in southwest Florida came from Gaspar. Many appeared on maps long before he supposedly arrived in the 1780s. "Gasparilla Island" is on Spanish and English maps from the early 1700s. Old documents suggest the island was named after Friar Gaspar, a Spanish missionary who visited the native Calusa people in the 1600s. Some stories say "Gasparilla" means "Gaspar, the outlaw" in Spanish. But it actually means "little Gaspar" or "gentle Gaspar." This name is more likely for a peaceful priest than a fierce pirate.

No Physical Proof

Gasparilla Island is a narrow island at the mouth of Charlotte Harbor. It is about 7 miles (11 km) long. The Gaspar legend claims he built a "royal" home base there. The first written story said his hideout had over a dozen buildings and a tall watchtower on an "ancient Indian mound filled with gold and the bleached bones of his victims." But no physical proof of these claims has ever been found.

Gasparilla Island became a busy shipping spot in the late 1800s when phosphate was found nearby. Modern port facilities, a railway, and the first bridge to the mainland were built then. Great sport fishing waters helped the area become a tourist spot. The Gasparilla Inn & Club opened, and the town of Boca Grande was established in the early 1900s. Many homes, a golf course, and Gasparilla Island State Park were built over the 20th century. Almost all of Gasparilla Island has been developed, but no trace of Gaspar's "pirate kingdom" has ever been found.

Over the years, the belief that Gaspar was real has led to rumors about mysterious maps and gold coins. People looking for treasure have searched for his lost riches across southwest Florida. But no part of his treasure or the remains of his many supposed victims have ever been found. Sadly, unauthorized treasure hunters have damaged important Native American sites. The Boca Grande Historical Society says that Calusa and other Native American sites in the Charlotte Harbor area have suffered "unimaginable damage" from "looters looking for a non-pirate's non-treasure."

Where the Legend Came From

The exact start of the Gaspar legend is not clear. Local folklore about pirates, Spanish explorers, and the native Calusa people grew in southwest Florida as towns developed in the late 1800s. At that time, the Ten Thousand Islands to the south were still wild. They were a hiding place for outlaws, but these were criminals on land, not pirates at sea.

These stories were told by word of mouth and not written down much. No mention of a pirate named Jose Gaspar has been found from the 1800s. But in the early 1900s, several people and groups helped turn different pirate stories into the legend of the made-up Jose Gaspar. He soon became very popular further north along Florida's Gulf coast.

John Gómez, the Storyteller

John Gómez (also known as Juan Gómez and Panther John) was a real person whose life became mixed with the José Gaspar legend. In the late 1800s, Gómez lived in a shack on Panther Key, a small island near Marco Island in southwest Florida. He was known along Florida's Gulf coast as a great hunting and fishing guide, boat pilot, and a funny storyteller. He often told "tall tales" about himself. His age and birthplace changed often, even on official papers. He died in a boating accident in 1900.

Gómez's uncertain birth was just the start of his supposedly very long and adventurous life. He claimed to have seen Napoleon as a young man, sailed the world, served in the U.S. Army during the Seminole Wars, and was a pilot for the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. He also claimed to have been involved in filibustering (and maybe pirating) in Central America and the Caribbean. He even said he escaped a Cuban prison just before he was to be executed. None of these stories can be proven. However, records show Gómez lived in several places around southwest Florida from about 1870 until his death.

Because he told entertaining stories and was skilled as a boat pilot and outdoorsman, Gómez became a popular guide. He was mentioned in Forest and Stream, an early magazine about nature. His tall tales were usually shared during fishing or hunting trips. They are only written down in a few personal accounts and his obituary. However, even though many Gasparilla legends claim Gómez was the last surviving member of the pirate's crew, no old accounts of Gómez's life or stories mention José Gaspar. The connection was first made after Gómez died in 1900. A brochure for a Charlotte Harbor resort hotel claimed that the late John Gómez was the main source of its story about the pirate Gasparilla.

Since then, many detailed and often different stories have been told about Gómez's supposed adventures with José Gaspar. Some say Gómez was the pirate's cabin boy, others that he was Gaspar's brother-in-law and first mate. Some even suggest Gómez was the very long-lived José Gaspar himself, living under a different name. Most legends also claim Gómez knew where Gaspar's huge treasure was. This seems unlikely, as Gómez asked the Lee County Commission for $8 a month because he was poor.

The Gasparilla Inn Brochure

The first known written story of José Gaspar came from a brochure for the Gasparilla Inn Resort. This was in the early 1900s in the new tourist town of Boca Grande, Florida on Gasparilla Island. Publicist Pat Lemoyne wrote it for the Charlotte Harbor and Northern Railway Company, which had just opened the resort. The brochure had two parts: the legend of José Gaspar and a section promoting the Gasparilla Inn and the Charlotte Harbor area. It was given out to guests and in northern cities to attract tourists.

The brochure's cover showed a colorful picture of Gaspar. The introduction claimed the pirate story inside came from tales told by the recently deceased John Gómez, who was described as the oldest surviving crew member. Several parts of Gaspar's story first mentioned in this brochure were repeated and made bigger in later tellings. This includes the tale of the "little Spanish princess" and the details of his dramatic death. It also tried to link Gaspar to Charlotte Harbor. It claimed his large home base covered several islands in the area. Captiva Island was said to be where his captives were held. Sanibel Island was named after Gaspar's love interest. And his home was on Gasparilla Island. It said he "chose the best of the islands in Charlotte Harbor for his own secret haunts." Finally, it claimed a burial mound "forty feet high and four hundred feet in circumference" near Gasparilla Island had been found. It supposedly contained "ornaments of gold and silver" and "hundreds of human skeletons." But it also said most of the pirate's huge buried treasure "still lies unmoved" nearby, close to the Gasparilla Inn.

Even though the brochure presented its "romantic" history of Gaspar as true, it was completely made up. The local place names mentioned were there long before the pirate supposedly arrived. And despite exciting tales about finding gold and human remains, no such items or any other physical proof of Gaspar's "royal" home base, victims, or treasure has ever been found on Gasparilla Island or anywhere else in the Charlotte Harbor area.

In 1949, a retired Pat Lemoyne gave a talk. He happily admitted that his story of José Gaspar was a "cockeyed lie without a true fact in it." He said he wrote the brochure in an exciting way that "tourists like to hear." He explained that the story was inspired by John Gómez's tall tales, which Lemoyne had heard from others. Lemoyne described Gómez as a "colorful" person who claimed to be a pirate to sell fake treasure maps to people who believed him.

Piracy in the West Indies and Its Suppression

In 1923, historian Francis B. C. Bradlee received a copy of the Gasparilla Inn brochure. He thought the story of Gasparilla was real. So, he included many details in his book Piracy In The West Indies And Its Suppression. He did not try to check if the information was true. His book repeated claims that a "burying ground" with the "bleached bones" of Gaspar's victims had been found on Gasparilla Island. It also said a tall "burial mound" built by an "ancient race" had been dug up. It was supposedly full of gold and silver items and "hundreds of human skeletons." It also claimed a dying John Gómez confessed to seeing the "Little Spanish princess" murdered. He supposedly drew a map that led people to her body. However, none of these claims were true. No treasure, murder victims, or other physical proof of Gaspar's adventures has ever been found. And John Gómez drowned while fishing alone, so a deathbed confession was impossible.

Even though he didn't check facts, Bradlee's book was used as a source for later books. These included Philip Gosse's Pirates' Who's Who and Frederick W. Dau's Florida Old and New. The authors of these books also believed Gaspar was real. Over the next few decades, more books about pirates or Florida history wrongly included José Gaspar as a real historical figure. This led to ongoing confusion about whether he was real and repeated attempts to find his lost treasure.

Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla (YMKG)

In 1904, leaders in Tampa decided to make the city's May Day festival more exciting. They added a pirate "invasion" inspired by the still-new legend of Jose Gaspar. They also added parts from Mardi Gras in New Orleans. The event was popular. So, leading citizens started "Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla" (a club like the krewes of Mardi Gras). This group would organize future events, which became known as the Gasparilla Pirate Festival. In 1936, YMKG asked Tampa Tribune editor Edwin D. Lambright to write an official history of the group. Along with the real history of the Krewe and the festival, the book included a version of the José Gaspar legend. In this version, Gaspar was shown as a "respectable" and "courtly" pirate who only used violence when he had to. Lambright claimed his story of Gaspar was supported by "unquestionable records." These included a diary supposedly written by the pirate himself and taken to Spain by a crew member, perhaps Juan Gómez. However, the diary was said to be lost, and no other proof was ever shown.

In 2004, YMKG published a new history for its 100th anniversary. This document tells the Gasparilla legend first published in 1936. But it also adds that research in Spanish and American records has not found any proof of Gaspar's existence.

"The Hand of Gasparilla"

In the 1930s, a construction worker named Ernesto Lopez showed his family a mysterious box. He claimed he found it while working on the Cass Street Bridge in downtown Tampa. Family stories say the wooden box held Spanish and Portuguese coins. It also had a severed hand wearing a ring with "Gaspar" engraved on it. And there was a "treasure map" showing Gaspar's treasure was hidden near the Hillsborough River in Tampa.

In 2015, Lopez's great-grandchildren found a box in their late grandfather's attic. It seemed to contain the items Ernesto Lopez had found, along with his wedding photo. The family told a local reporter, and the TV news report about the strange find was picked up by national and international news. However, experts at the Tampa Bay History Center looked at the box. They found it contained old coins that were not valuable, souvenirs from early Gasparilla parades, and a map from the 1920s showing local streets and businesses. The origin of the hand remained a mystery. The history center's curator thought it might be a mummified monkey hand.

Gaspar's Legacy Today

The Gasparilla Pirate Festival

In 1904, business leaders in Tampa created a surprise pirate "invasion" during the city's quiet May Day celebration. As "Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla" (YMKG), a group like the New Orleans Mardi Gras krewes, the "invaders" dressed as pirates. They rode horses through the streets, encouraging people to follow them to the party. The event was a big hit. The next year, the Krewe organized a parade where all 60 of Tampa's cars drove through downtown. The first "invasion" by sea happened in 1911. YMKG has organized a pirate invasion and parade almost every year since.

Tampa now hosts many community events during its "Gasparilla Season," which runs from about January to March. The main event is still an "invasion" by José Gaspar and his crew. This happens on the last Saturday in January. Members of Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla, with hundreds of private boats, sail across Tampa Bay to downtown Tampa. They sail on the José Gasparilla, a 165-foot-long "pirate" ship built for this purpose in 1954. The mayor of Tampa then gives the key to the city to the "pirate captain." A "victory parade" follows down Bayshore Boulevard. Dozens of other Krewes have joined the fun over the years. This has grown into one of the largest parades in the United States. Over 300,000 people attend the event, which brings in over $20 million for the local economy.

Cultural Connections

- Since no one group owns the names "Gaspar" or "Gasparilla," many businesses, groups, and events in the greater Tampa Bay area use them. Others have names inspired by the mythical pirate. For example, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers of the National Football League started playing in 1976. Another sports example is the Gasparilla Bowl, a college football bowl game. It was once called the "St. Petersburg Bowl" but changed its name when it moved to Tampa in 2018.

- The legend of Gasparilla has been shown in several TV shows and books. Recent examples include episodes in September 2019 of the TV series Expedition Unknown on the Discovery Channel and Code of the Wild on the Travel Channel. Both shows followed amateur treasure hunters (who didn't find anything) looking for Gaspar's treasure in the Charlotte Harbor area.

See also

In Spanish: José Gaspar para niños

In Spanish: José Gaspar para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |