Katipō facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Katipō |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Female katipō | |

| Conservation status | |

Serious Decline (NZ TCS) |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Araneae |

| Infraorder: | Araneomorphae |

| Family: | Theridiidae |

| Genus: | Latrodectus |

| Species: |

L. katipo

|

| Binomial name | |

| Latrodectus katipo Powell, 1871

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The katipō (Latrodectus katipo) is a special type of spider that lives only in New Zealand. It's an endangered species, meaning it's at risk of disappearing forever. The katipō is part of a group of spiders called Latrodectus spiders, which also includes the Australian redback and the North American black widow.

Katipō spiders are small to medium-sized. Female katipō spiders have a round body, about the size of a pea. They can be black or brown. Red katipō females, found in the South Island and lower North Island, are black with a clear red stripe on their back, outlined in white. Black katipō females, found in the upper North Island, might not have this stripe, or it could be pale yellow or cream-coloured. Scientists used to think these were different species, but now we know they are just different colours of the same spider!

Male katipō spiders are much smaller than females and look quite different. They are white with black stripes and red diamond shapes. Katipō spiders mostly live in sand dunes near the beach. They catch insects in their messy, tangled webs, which they spin among dune plants or other things like driftwood.

Contents

What is a Katipō?

The katipō spider was first officially described in 1870. Spiders in the Latrodectus group, like the katipō, are found all over the world. This group includes well-known spiders like the North American black widow and the brown widow. The katipō's closest relative is the Australian redback spider.

Scientists once thought the katipō and the black katipō were separate species. However, research has shown they are the same species, just with different colours depending on where they live and the temperature. The katipō is also closely related to the redback, but it's a distinct species because it has small body differences and prefers different places to live.

The name "katipō" comes from the Māori words kakati (to sting) and pō (the night). This name was given because Māori people believed the spiders bit at night. Other names for it are red katipō, black katipō, and New Zealand's redback.

How to Spot a Katipō

The katipō is a small to medium-sized spider. An adult female's body is about 8 millimetres (0.31 in) long, and her legs can stretch up to 32 millimetres (1.3 in).

The red katipō female, found in the South Island and lower North Island, has a black, round body like a garden pea. She has thin legs and a white-bordered orange or red stripe on her back. This stripe goes from the top of her body all the way to her spinnerets (where she spins silk). Her black body looks soft and velvety, not shiny. Underneath her body, she has a red patch or a partial red hourglass shape. Her legs are mostly black, turning brown at the ends.

The black katipō female, found in the upper North Island, doesn't have the red stripe on her back. Her body is usually lighter in colour, but she looks very similar to the red katipō. The hourglass pattern under her body might be less clear or even missing. Sometimes, katipō spiders can even be brown, with a dull red or yellow stripe, or cream-coloured spots. All these different looks were once thought to be different species, but a study in 2008 proved they are all the same kind of katipō.

Young katipō spiders and adult males look very different from the females. They are much smaller, about one-sixth the size of an adult female. Young spiders have a brown head and chest area, with a mostly white body that has red-orange diamond shapes down the middle, bordered by black lines. Males keep these colours when they grow up. Because of their small size, people once thought male katipō spiders were a completely different species!

Where Katipō Spiders Live

Katipō spiders live in a very specific place: near the seashore among sand dunes. They usually stay on the side of the dunes closest to the land, where they are safe from storms and sand moving around. Sometimes, they can be found several kilometres inland if the dunes stretch that far.

They build their webs in low-growing dune plants, like the native pīngao plant or the introduced marram grass. They might also build their webs under driftwood, stones, or even old tin cans or bottles. Katipō webs are almost always built over open sand and close to the ground. This helps them catch invertebrates that crawl along the sand.

Katipō spiders prefer to build their webs among pīngao plants. This is because pīngao grows in a way that leaves open patches of sand between the plants. The wind can then blow insects into these gaps and right into the spider's web. Marram grass, which has been planted a lot in New Zealand to help stop sand dunes from moving, grows very tightly. This makes it hard for katipō spiders to build webs that can catch prey.

Like other tangle-web spiders, the katipō's web is a messy, irregular tangle of fine, yellowish-white silk. It's shaped like a hammock with many support threads. The spider builds a cone-shaped hideaway in the lower part of the web, but it's usually found near the main part of the web. The plants it builds its web in help support and protect its home.

Katipō Spider Range

The katipō spider is found only in New Zealand. In the North Island, it lives along the West Coast from Wellington up to North Cape. On the East Coast of the North Island, it's found in some places, and it's very common on Great Barrier Island. In the South Island, it lives in coastal areas south to Dunedin on the east coast and south to Greymouth on the west coast. Katipō spiders need temperatures warmer than about 17 °C (63 °F) for their eggs to develop, which is why they don't live in the colder southern parts of New Zealand.

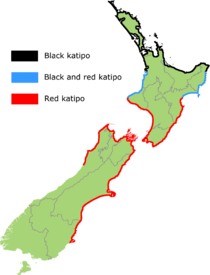

The red katipō is found south of about 39°15′ S (around the western tip of Taranaki and just north of Waipatiki Beach in Hawke's Bay). The black katipō is found north of about 38° S (around Aotea Harbour and Waipiro Bay). Both types of katipō can be found in the area between these two lines.

Katipō Behaviour

Diet and Hunting

The katipō spider usually catches invertebrates that walk on the ground, like beetles or amphipods. Sometimes, it might also catch moths, flies, or even other spiders. Katipō spiders can catch insects much bigger than themselves!

When a large insect gets caught in the web, it often struggles so much that the web's anchor lines break. The web's stretchy silk then pulls the prey a few centimetres off the ground. The katipō moves to the prey, turns around so its silk-spinning parts (spinnerets) face the insect, and quickly spins more silk over it. It uses special comb-like bristles on its back legs to scoop sticky silk and throw it over the insect.

Once the insect is stuck, the spider bites it several times, usually at its joints. Then, it spins more silk to make the web stronger and gives one last long bite to kill the insect. The spider then moves its prey up into the web to save it for later. If there's lots of food, you might see five or six insects hanging in the web, waiting to be eaten! Male katipō spiders hunt in a similar way, but they might not be as strong because they are smaller.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

In August or September, the adult male katipō spider goes looking for a female's web to mate. When he enters her web, he vibrates the silk to let her know he's there. The female is usually aggressive at first and will chase him away. The male will keep bobbing, plucking, and tweaking the web, carefully approaching and being chased, until the female calms down. Once she lets him get close, he mates with her while she hangs upside down in the web. After mating, the male cleans himself. Unlike some other widow spiders, the male katipō is usually not eaten by the female.

Female katipō spiders lay their eggs in November or December. The eggs are round, about the size of a mustard seed, and are a see-through purplish-red colour. They are held together in a cream-coloured, round, ball-shaped egg sac, about 12 millimetres (0.47 in) across. The female makes five or six egg sacs over the next three to four weeks. Each egg sac holds about 70 to 90 fertilised eggs.

The female hangs the egg sacs in the middle of her web and spins more silk over them. Over time, the outside of the egg sac might get covered with sand. After about six weeks, in January and February, the baby spiders (spiderlings) hatch. The young spiders then leave the web.

We don't know much about how the spiderlings move away from the nest. Some might use a "ballooning" method, where they use air currents to carry themselves away on a single strand of silk. Others might use a "bridging" method, using their silk to move to nearby plants. The young spiderlings become fully grown the following spring.

The close relationship between the katipō and redback spiders is clear when they mate. A male redback can successfully mate with a female katipō, creating hybrid babies. However, a male katipō cannot mate with a female redback. This is because the male katipō is heavier than the male redback. When a male katipō approaches a female redback's web, it triggers her hunting instinct, and she might eat him before they can mate. There is even evidence that katipō and redbacks interbreed in the wild.

Who Eats Katipō Spiders?

The katipō spider has only one known natural predator: a small, unknown native wasp. This wasp has been seen feeding on katipō eggs.

Why Katipō Spiders are Disappearing

The katipō is an endangered species and is at risk of extinction. It's thought that there are only a few thousand katipō spiders left. They live in about 50 areas in the North Island and eight areas in the South Island. This makes them rarer than some types of kiwi birds!

Many things have caused their numbers to drop. The main reasons are that their natural habitat is being destroyed or changed. Humans have been changing coastal dunes for over a century for things like farming, forestry, or building cities. Fun activities like using beach buggies, off-road vehicles, horse riding on beaches, and collecting driftwood also damage the areas where katipō live. Many new, non-native plants have also grown in their habitat, making it unsuitable for them.

Other spiders from different countries have also moved into the areas where katipō spiders live. The main one is a spider from South Africa called Steatoda capensis. This spider was first seen in the 1990s. It might have taken over areas where the katipō used to live, especially along the west coast of the North Island. However, both katipō and S. capensis have been found living in the same dune systems or even under the same piece of driftwood, which means they can sometimes live together.

It's possible that S. capensis is better at moving back into areas after storms or other changes to the dunes. Also, S. capensis breeds all year round, has more babies, and can live in more types of habitats. This puts more pressure on the katipō. S. capensis is in the same spider family as the katipō and looks very similar in size, shape, and colour. But it doesn't have the red stripe on its back, though it might have some red, orange, or yellow on its body. Because they look so alike, S. capensis is often called the "false katipō" in New Zealand.

In 2010, the katipō was one of a few invertebrate species that were given full protection under the 1953 Wildlife Act. This means it's now illegal to kill a katipō spider, and breaking this law can lead to a fine or even jail time.

Katipō Bites and Safety

The katipō spider has venom that can affect humans, but bites are very rare. Katipō spiders are shy and not aggressive. Because they live in a small area, their numbers are decreasing, and people know where they live, humans don't often come across them.

A katipō will only bite as a last resort. If bothered, the spider usually curls up into a ball and drops to the ground or hides. If the threat continues, the spider might throw silk at what's bothering it. If it's trapped or held against skin, like if it gets tangled in clothing, it might bite to defend itself. However, if a female spider is with her egg sac, she will stay close to it and might even move to bite any threat.

Bites from katipō spiders can cause a set of symptoms known as latrodectism. The venom contains a special substance called alpha-latrotoxin, which is the main cause of these symptoms. Most bites come from female spiders. While male katipō spiders are much smaller, male redback spiders (a close relative) have been known to bite humans, suggesting male katipō spiders could too. However, bites from males are much rarer, possibly because their jaws are smaller.

Historically, there were reports of severe katipō bites in the 1800s and early 1900s. However, no deaths from spider bites have been reported in New Zealand since 1901. The most recent reported katipō bites were to a tourist in 2010 and a kayaker in 2012.

Symptoms of a Bite

The symptoms of a katipō bite are similar to those from other Latrodectus spiders. The main symptom is usually extreme pain. At first, the bite might feel like a small prick or a mild burning. Within an hour, people usually feel more severe pain where they were bitten, along with local sweating and sometimes goosebumps. The pain, swelling, and redness can spread from the bite area.

Less commonly, other symptoms can appear, like swollen or sore lymph nodes, feeling unwell, nausea, vomiting, stomach or chest pain, sweating all over, headache, fever, high blood pressure, and shaking. Very rarely, more serious problems can happen, but these are extremely uncommon. The effects can last from a few hours to several days, with severe pain sometimes lasting over 24 hours.

Treatment for a Bite

Treatment for a katipō bite depends on how severe it is. Most bites don't need medical attention. If there's only local pain, swelling, and redness, applying ice and taking regular pain relief usually helps. If simple pain relief doesn't work, or if other symptoms appear, it's a good idea to get checked at a hospital.

For more severe bites, an antivenom (a medicine that helps fight the venom) can be given. The antivenom used for redback spiders also works for katipō venom. This antivenom is available at most major New Zealand hospitals. It usually helps relieve the symptoms and is recommended if someone has symptoms that match a Latrodectus spider bite. It's especially used for spreading pain, sweating, or high blood pressure. While there's some debate about how well antivenoms work for all spider bites, pain relief medicine might also be needed.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |