Kelvin Grade massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kelvin Grade massacre |

|

|---|---|

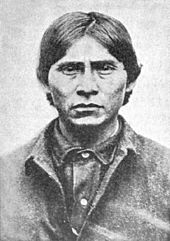

The Apache Kid in 1889, as a prisoner in Globe

|

|

| Location | near Globe, Arizona |

| Date | November 2, 1889 |

|

Attack type

|

Murder, prison escape |

| Weapons | Small arms |

| Deaths | 2 |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

1 |

| Victims | American citizens |

| Perpetrators | Apache |

The Kelvin Grade incident happened on November 2, 1889. It was a time when nine Apache prisoners escaped from police while being moved near Globe, Arizona. This escape led to the deaths of two sheriffs. It also started one of the biggest searches for people in Arizona's history. People who had fought in the Apache Wars looked for the escapees for almost a year. In the end, all were caught or killed, except for a famous Indian scout known as the Apache Kid.

Contents

Why the Escape Happened

When the reservation system started in Arizona, the local Apache people were among the first to live on them. For much of the Old West period, these reservations often did not have enough food or supplies. Also, some people in charge were not fair. This led to conflicts, like Geronimo's War in 1881. During this time, Geronimo and his group of Apaches left their reservations and avoided capture until 1886.

The Apache Kid's Story

The Apache Kid, whose Apache name was Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl, worked as an Indian scout for the U.S. Army in the Apache Wars for most of the 1880s. He was involved in a disagreement during the Battle of Cibecue Creek and the Crawford Affair. Many people at the time believed the Apache Kid did not kill any soldiers at Cibecue. However, he left the reservation system in 1887 after an event at the San Carlos Reservation.

The Kid was also a friend of Al Sieber, who was the Chief of the Army Scouts. Some say Sieber later betrayed the Kid after the Cibecue event. Around 1888, the Apache Kid was caught and put on trial in Globe for various wrongdoings. He was sentenced to seven years in Yuma Territorial Prison. The Kid had already spent over a year in prison at San Carlos and Alcatraz Island. He did not want to go to the prison at Yuma. So, he secretly planned with other prisoners to escape whenever they could.

The Journey to Yuma

On the morning of November 1, 1889, Sheriff Glenn Reynolds arrived at the jail in Safford. He was there to pick up eight Apache prisoners and one Mexican man. They were to be moved to Casa Grande by stagecoach, which was a two-day trip. From Casa Grande, they would take a train to Yuma.

Sheriff Reynolds arranged for stagecoach owner Eugene Middleton to take them to Casa Grande. Middleton had survived several conflicts with Apaches since 1881. Reynolds also collected $400 from the county clerk to pay for the trip. Sheriff William A. "Hunkydory" Holmes joined Reynolds and Middleton.

Once the prisoners were in the coach, the group headed north towards Globe. Sheriff Reynolds rode his horse, Tex, while Middleton and Holmes rode in the coach. The trip was long. Holmes spent his time practicing shooting his rifle. After stopping for lunch in Pioneer, Arizona, the group continued to the Gila River in a rainstorm. Just past the Gila River was a small town called Kelvin, or Riverside Station. The group stopped there for the night.

The Escape at Kelvin Grade

On the next morning, Saturday, November 2, Sheriff Reynolds woke everyone early. He wanted to leave by 5:00 AM to reach Casa Grande that night before the train left. Around this time, Reynolds worried about a part of the road outside of town called Kelvin Grade. He also left his horse Tex behind to ride in the coach with Holmes.

The road was very steep. With nine prisoners in the coach, the horses were not strong enough to pull the wagon up, especially after the heavy rain the night before. To get up Kelvin Grade, Reynolds decided the prisoners would have to get off and walk. When they reached the grade, seven prisoners got off as planned. But the Apache Kid and one other man were thought to be too dangerous, so they stayed in the coach. Middleton also stayed to drive the coach. Reynolds led the walking prisoners, with Holmes at the back.

The coach went up the grade first, followed by the line of prisoners and sheriffs. The prisoners were all in handcuffs and tied together in pairs, except for Jesus Avott, the Mexican man. Slowly, two of the Apaches moved close to Reynolds, who was not expecting anything. After the coach went out of sight, they suddenly jumped on the sheriff to take his shotgun.

At the same time, another pair of Apaches attacked Holmes and took his rifle. The prisoner Pas-Lau-Tau shot Reynolds, who died right away. Holmes later died from a heart attack. Just after the fight started, Avott ran ahead to warn Middleton. Middleton thought the shots were just target practice. When Avott reached the coach, Middleton told him to get in, but Avott hid in some bushes instead. Bach-e-on-al was not far behind and soon shot Middleton in the head. The bullet went through his mouth without hitting any teeth and came out his neck. Amazingly, Middleton survived and stayed awake. After that, the other prisoners came up and freed the Kid from inside the coach. One of the escapees, El-cahn, was going to hit Middleton's head with a rock while he lay helpless. But the Kid stopped him, perhaps remembering that Middleton had shared cigarettes with him the night before.

What Happened Next

After the attack, the Apache Kid and the others took items from the dead sheriffs and Middleton, including their clothes, jewelry, and weapons. Then they ran into the desert. Jesus Avott was still hiding. Once the Apaches were gone, Avott untied a horse from the coach to ride to town. But the horse kicked him off.

However, a rancher nearby, Andronico Lorona, was moving cattle through the area. He saw the stopped coach and decided to check it out. Lorona found Avott there and gave him a horse to ride into Florence. Lorona then left to tell his foreman about the prisoners' escape. The foreman sent a group of cowboys to guard the bodies. Because of his help, Avott was pardoned and did not have to go to Yuma prison.

Sometime before the cowboys arrived, Middleton found the strength to stand up. But he could not get onto the coach or a horse. So he had to walk and crawl a long way back to Riverside Station. When Middleton reached Riverside, he received medical help and told the townspeople what had happened.

The Search Begins

Shorty Sayler, a stagecoach driver, took Reynolds' horse Tex and rode it to Globe, forty miles away, to tell the authorities. Sayler stopped and changed horses in Pioneer. He reached Globe in record time, arriving before noon that same day. The telegraph operator at Globe was Dan Williams. He later said, "I was the receiving operator and quickly told Al Sieber the terrible news. He commented, ‘I was afraid of that, and that was why I offered a scout escort to Casa Grande.'" From his bed, Sieber directed a group of twenty scouts under Lt. Watson to follow the trail from San Carlos.

Deputy Sheriff Jerry Ryan took Reynolds' place after learning of his death. But because the escape happened in Pinal County, Sheriff Jerry Fryer took charge of the investigation. Sheriff Ryan sent a telegram to Captain Bullis at San Carlos, who then told General Nelson A. Miles. For several months, until October 1890, American militias, people hired to find them, and United States Army troops searched the Arizona desert for the escaped prisoners. All of them were eventually caught or killed, except for the Kid.

Later Sightings of the Apache Kid

Between 1889 and 1894, several deaths and small fights happened between settlers and Apaches. Most of these were thought to be caused by the Apache Kid and his friend Massai, another former army scout. Massai was said to have been killed by a group in September 1906.

At one point, a person named Mickey Free, who was hired to find the Kid, told Al Sieber that he had followed the Kid for three months before killing him. As proof, he said he carved a tattoo of the letter "W" on him. This "W" had been tattooed in blue ink on the foreheads of about 100 San Carlos Apache people before the army started a new way to identify them. The Kid is not known to have had such a tattoo, but Mickey Free, who knew the Kid well, said he did.

In 1890, some Mexican Rurales (police) killed an Apache and found Sheriff Reynolds' pistol and watch. This first made them think they had killed the Kid. But the dead man was said to be much older than the Kid. In 1896, John Horton Slaughter also claimed to have killed the Apache Kid in the Sierra Madre mountains of Chihuahua, Mexico. Apache groups were still living there as late as 1915. But because Slaughter had crossed the international border, he kept quiet about it, fearing trouble with his leaders. A native man named Wallapai Clark also said he shot the Kid when he tried to steal his horse from a pen. In 1899, the colonel of the Rurales, Emilio Kosterlitzky, claimed the same when his men killed three Apaches.

In 1924, after a group of Apaches crossed into Arizona to take horses, the Kid’s nephew, Private Joe Adley of Fort Huachuca, told Lieutenant John H. Healy of the 10th Cavalry that the Apache Kid was still alive in Mexico. This was mostly confirmed by Guadalupe Fimbres Muñoz. She was captured in 1915 during a surprise attack on Apache Juan’s camp in the Sierra Madre. She had been one of the guards for the Apaches and had sounded the warning that allowed the others to escape. At first, many thought she was Geronimo's granddaughter, while others said her father was Apache Juan. However, Guadalupe herself claimed that her father was the Apache Kid. People reported seeing the Kid as late as 1935 when he was supposedly visiting friends at San Carlos.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |