Kenesaw Mountain Landis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

|

|

|---|---|

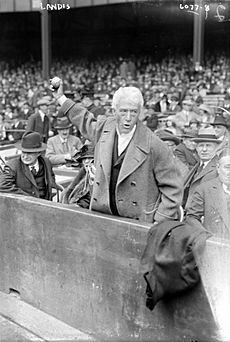

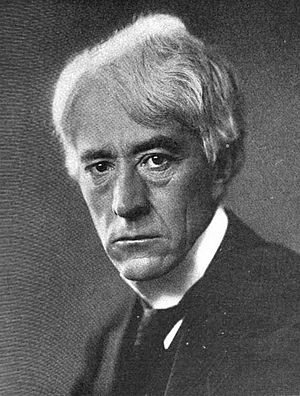

Landis, c. 1922

|

|

| 1st Commissioner of Baseball | |

| In office November 12, 1920 – November 25, 1944 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Happy Chandler |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois | |

| In office March 18, 1905 – February 28, 1922 |

|

| Appointed by | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Seat established by 33 Stat. 992 |

| Succeeded by | James Herbert Wilkerson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Kenesaw Mountain Landis

November 20, 1866 Millville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 25, 1944 (aged 78) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Woods Cemetery Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Winifred Reed

(m. 1895–1944) |

| Children | 3, including Reed |

| Relatives | Charles Beary Landis (brother) Frederick Landis (brother) |

| Education | Union College of Law read law |

| Signature | |

| Nicknames |

|

|

Baseball career |

|

| Induction | 1944 |

| Election Method | Old Timers' Committee |

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American judge. He later became the first Commissioner of Baseball. He held this position from 1920 until his death. He is most famous for his actions during the Black Sox Scandal. In this scandal, eight players from the Chicago White Sox were accused of planning to lose the 1919 World Series. Landis kicked these players out of baseball forever. His strong leadership helped people trust the game again.

Landis was born in Millville, Ohio. His unique first name came from Kennesaw Mountain, a battle site in the American Civil War. His father was hurt there. Landis grew up in Indiana. He became a lawyer and then worked for the U.S. Secretary of State.

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt made Landis a federal judge. Landis became well-known in 1907. He fined a large oil company, Standard Oil of Indiana, a huge amount of money for breaking laws. This showed he was a judge who wanted to control big businesses. After World War I, Landis oversaw trials of people who opposed the war. He gave them strict punishments.

In 1920, baseball team owners were facing problems. The Black Sox scandal and other game-fixing rumors made them worried. They wanted someone strong to lead baseball. They chose Landis to be the first Commissioner of Baseball. He was given full power to make decisions for the sport. He used this power for nearly 25 years. Many people praised Landis for making baseball fair again. However, some of his decisions, like banning "Shoeless Joe" Jackson and Buck Weaver, are still debated. Some also believe he delayed the racial integration of baseball. Landis was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame shortly after he died in 1944.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Growing Up and Starting Out (1866–1893)

Kenesaw Mountain Landis was born on November 20, 1866, in Millville, Ohio. He was the sixth child of Abraham and Mary Landis. His father was a doctor. Abraham Landis was hurt fighting in the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. Because his parents couldn't agree on a name, his mother suggested "Kenesaw Mountain."

When Kenesaw was eight, his family moved to Indiana. His father, due to his war injury, bought and ran farms. Kenesaw had four brothers. Two of them, Charles Beary Landis and Frederick Landis, later became members of Congress.

Young Kenesaw, sometimes called "Kenny," did a lot of farm work. He started working off the farm at age ten as a newsboy. He left school at 15 and worked at a general store. Then he worked for a railroad. He wanted to be a brakeman but was too small. He later worked for a newspaper and taught himself shorthand. In 1883, he became a court reporter. He was proud of his shorthand skills. In his free time, he was a bicycle racer and played baseball. He turned down a professional baseball contract. He said he preferred to play for fun.

In 1886, Landis got involved in politics. He supported a friend for Indiana Secretary of State. His friend won, and Landis got a government job. While working there, he became a lawyer. He opened a law office in Marion, Indiana. But he didn't get many clients. He decided to go to law school. He studied at Union Law School (now part of Northwestern University). He earned his law degree in 1891. He then started a law practice in Chicago.

Working in Washington (1893–1905)

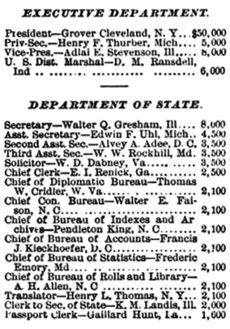

In 1893, President Grover Cleveland appointed federal judge Walter Q. Gresham as his Secretary of State. Gresham hired Landis as his personal secretary. Landis worked hard in Washington. He made friends with many reporters. Some older officials in the State Department found him too bold.

Once, information about the President's policy leaked. The President thought Landis was the source. He demanded Landis be fired. But Gresham defended Landis. He said the President would have to fire both of them. The President changed his mind. He later found out he was wrong about Landis. President Cleveland grew to like Landis. When Gresham died in 1895, Cleveland offered Landis a job as an ambassador. Landis turned it down. He wanted to return to Chicago. He planned to start a law practice and marry Winifred Reed. They married on July 25, 1895. They had two children who survived, Reed and Susanne.

Landis built a successful law practice in Chicago. He also became very active in the Republican Party. He worked closely with his friend Frank O. Lowden. Lowden later became governor of Illinois. A judge position opened up in Chicago. President Theodore Roosevelt offered it to Lowden. Lowden said no and suggested Landis instead. Roosevelt wanted a strong judge. On March 18, 1905, Roosevelt nominated Landis. The Senate quickly approved him the same day.

Judge Landis (1905–1922)

Landis's courtroom in Chicago was very fancy. It had murals and was made of mahogany and marble. Writers soon noticed Landis's dramatic style. He was known for his strong opinions. He would wrinkle his nose if he suspected a lawyer. He once told a witness to "stop fooling around."

When an elderly man faced a five-year sentence, Landis asked him, "Well, you can try, can't you?" Another time, a young man stole jewels. His wife stood with their baby. Landis paused dramatically. Then he told the young man to go home with his family. He didn't want the girl to be the daughter of a convict. People in the courtroom were very moved.

When Landis became a judge, companies expected him to favor them. But he didn't. In one early case, he fined a company the maximum amount. This was for illegally bringing in workers. Even though his wife's brother-in-law was on the company's board. He also supported the government's power to stop railroads from giving special low prices to some customers.

The Standard Oil Case (1905–1909)

In the early 1900s, large companies called "trusts" controlled many industries. They often raised prices very high. The government tried to control these trusts. One of the biggest was Standard Oil, run by John D. Rockefeller.

In 1906, Standard Oil of Indiana was accused of breaking laws. They were getting secret low prices from a railroad. The case was given to Judge Landis. The company didn't deny getting the low prices. The main question was whether they knew the railroad's official rates. The jury found Standard Oil guilty on all counts.

Landis could fine the company up to $29,240,000. To decide the fine, Landis ordered Rockefeller to testify. Rockefeller had avoided court for years. Marshals searched for him. He was found and came to Landis's courtroom. A large crowd gathered to see him. Rockefeller said he knew almost nothing about Standard Oil's business.

On August 3, 1907, Landis announced his decision. He fined Standard Oil the maximum amount: $29,240,000. This was the largest fine ever given to a company at that time. Landis was seen as a hero. President Roosevelt was very pleased. Rockefeller was playing golf when he heard the news. He calmly told his friends the amount. He then played his best game ever. He said, "Judge Landis will be dead a long time before this fine is paid." He was right. The fine was later overturned by a higher court. In a new trial, Standard Oil was found not guilty.

Baseball and Other Cases (1909–1917)

Landis loved baseball. He often left court to watch the White Sox or Cubs. In 1914, a new league, the Federal League, challenged the existing major leagues. In 1915, the Federal League sued the older leagues. The case went to Landis. Baseball owners worried about the "reserve clause." This rule made players sign new contracts only with their old team.

Landis held hearings in early 1915. He told both sides that "any blows at the thing called baseball would be regarded by this court as a blow to a national institution." He didn't make a quick decision. Spring training and the whole season passed. In December 1915, the leagues settled the case. The Federal League closed down. Landis never said why he waited to rule. He told friends he knew they would settle.

In 1916, Landis oversaw the "Baby Iraene" case. A rich widow claimed a baby girl from Canada was her late husband's heir. But a shop girl from Ontario, Margaret Ryan, said the baby was hers. Ryan said she was told her baby died at birth. Landis listened to witnesses. He decided the child belonged to Ryan. People compared him to King Solomon. A higher court later said Landis didn't have the power to decide the case. A Canadian court later gave the child to Ryan.

World War I Cases (1917–1919)

In 1917, Landis thought about leaving his judge job. He loved being a judge, but the pay was low. However, when the United States entered World War I, he decided to stay. He strongly supported the war effort. He even asked to go to France to fight, but was told to give speeches instead. His son, Reed, became a pilot and a war hero.

Landis was very strict with people who opposed the war. In 1917, he tried about 120 men who resisted the draft. Most were foreign-born. Landis found them all guilty. He gave most of them the maximum sentence of a year and a day in jail. He also ordered some to be sent out of the country.

In September 1917, federal officers raided the offices of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). This union had opposed the war. Over 100 IWW leaders were charged. Their cases were given to Landis. The trial began in April 1918. It was the largest federal criminal trial at the time.

Landis conducted the trial fairly, despite his strong feelings. The jury found all remaining defendants guilty. Landis gave most of them long prison sentences. Some of these sentences were later reduced by President Calvin Coolidge. After leaving his judgeship, Landis still spoke harshly about these defendants.

Landis wanted to try the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, for war crimes. But the Kaiser fled to the Netherlands. Landis publicly demanded that the Kaiser and German military leaders "be lined up against a wall and shot."

War-related trials continued even after the war ended in 1918. Seven leaders of the Socialist Party of America, who had opposed the war, were charged. One of them was Victor L. Berger, who was elected to Congress. The defendants tried to move the trial away from Landis. They said he had made biased comments about Germans. Landis denied their request. The jury found Berger and his co-defendants guilty. Landis sentenced each to twenty years in prison. A higher court later overturned these convictions. They said Landis should have stepped aside. In 1922, the government dropped the charges.

Baseball Commissioner (1920–1944)

Becoming Commissioner

The Search for a Leader

Before Landis, baseball was run by a three-person group. But this group was often stuck because its members disagreed. Many team owners wanted one strong leader for the game. Landis's name was mentioned in newspapers for this role.

In September 1920, the Black Sox scandal became public. This made owners even more eager for a new system. They wanted a single commissioner who had no financial ties to baseball. Names like Landis and former President William Howard Taft were discussed.

On November 8, 1920, eleven team owners met. They all agreed to choose Landis as the head of the new baseball system. Other teams soon agreed too. On November 12, the team owners went to Landis's courtroom. Landis was in the middle of a trial. He made them wait until he finished his court business. Then he met with them.

Landis was at first unsure about taking the job. But he agreed to be Commissioner for seven years. His salary would be $50,000. He also insisted he could stay a federal judge. For a while, he did both jobs. The press praised his appointment. A month later, Landis signed an agreement. It gave him almost unlimited power over everyone in baseball. This included owners, players, and even batboys. He could ban people from baseball for life. The owners agreed not to sue him. Humorist Will Rogers said Landis would make "those baseball birds walk the chalkline."

Taking Control

Banning the Black Sox Players

The criminal case against the Black Sox players faced problems. Some evidence disappeared. Landis decided to act. He put all eight players on an "ineligible list." This banned them from all major and minor league baseball. The White Sox team supported Landis. They released the seven players still under contract. Most people were against the players.

The criminal trial for the Black Sox players began in July 1921. The jury found all defendants not guilty on August 2, 1921. There was great excitement in the courtroom. The players and jury celebrated together.

But Landis's ban remained. He said, "Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game, no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ball game, no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing a game are discussed and does not report it to his club or league official, will ever play professional baseball."

Many believe this decision was one of the most important things Landis ever did for baseball. It showed he was serious about keeping the game clean. Over the years, some players, like Jackson and Weaver, asked to be allowed back. Jackson was said to have been tricked into the plan. Weaver said he didn't take any money. Both played well in the series. But Landis never let them back. He said being at meetings with gamblers was enough to ban them. Even today, people try to get Jackson and Weaver reinstated. But Landis's ban is still in place.

Stopping Gambling in Baseball

Landis believed that horse racing gamblers caused the Black Sox scandal. He said he would never let them control baseball again. In 1921, the owners of the New York Giants bought a horse racetrack. Landis told them they had to choose between baseball and horse racing. They quickly sold the track.

Landis also dealt with other gambling cases. He banned Eugene Paulette of the Philadelphia Phillies in 1921. Paulette had met with gamblers. Landis also banned Joe Gedeon in 1921. Gedeon had admitted to meeting with gamblers who tried to bribe the Black Sox.

In 1922, Giants pitcher Phil Douglas wrote a letter suggesting he would take a bribe. The letter was given to Landis. Landis banned Douglas. In 1924, Giants player Jimmy O'Connell offered a player $500 to not play his best. The player reported it to Landis. O'Connell was banned. In total, Landis banned eighteen players from baseball. His strong actions helped stop gambling in the sport.

The Ruth-Meusel Barnstorming Incident

After the baseball season, players often played exhibition games. This was called "barnstorming." Players on World Series teams were not allowed to barnstorm. In 1916, some Red Sox players, including Babe Ruth, did barnstorm. They were fined a small amount.

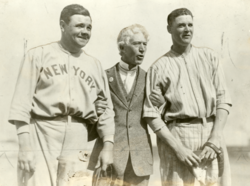

Ruth, who now played for the Yankees, was a huge star. He broke batting records in 1920 and 1921. After the 1921 World Series, Ruth wanted to lead a barnstorming tour. His teammate Bob Meusel also joined. This was against the rules. Ruth asked his team's general manager for permission. The manager said yes, but told Ruth to get Landis's approval.

Ruth did not contact Landis until the day before the first game. When they spoke, Landis ordered Ruth to meet him. Ruth refused, saying he had to leave for the game. Landis was very angry. He refused permission for Ruth to barnstorm. He reportedly said, "Who the hell does that big ape think he is?"

The tour was not successful. Landis ordered it banned from all baseball fields. It also had bad weather. In December, Landis suspended Ruth, Meusel, and another player until May 20, 1922. The Yankees and Ruth asked Landis to let them play earlier. But Landis refused. When Landis visited the Yankees in spring training, he lectured Ruth for two hours. Ruth later said, "He sure can talk."

When Ruth returned on May 20, he didn't play well. The crowd booed him. Landis knew that the public supported his strong decisions. This showed he had control over baseball.

Baseball Policies

Major and Minor League Relations

When Landis became commissioner, minor league teams were mostly separate from major league teams. Landis wanted to make sure players in the minor leagues could move up. Major league teams could draft players who played two years on the same minor league team. Landis worked to include all minor leagues in this draft system. By 1924, he succeeded.

By the mid-1920s, major league teams started creating "farm systems." These were minor league teams they owned. They used them to develop young players. Branch Rickey of the St. Louis Cardinals was a pioneer in this. The Cardinals became very successful with their farm system.

Landis made major league owners reveal their minor league interests. He fought against "covering up" players. This was when teams moved players between their own minor league teams. This made players ineligible for the draft. Landis's first official act as commissioner was to free a player named Phil Todt. He said the St. Louis Browns had tried to cover him up. In 1928, he freed future Hall of Famer Chuck Klein. In 1929, he freed Rick Ferrell, another future Hall of Famer. In 1936, he found that the signing of young pitcher Bob Feller was a trick. Feller was meant for the Cleveland Indians. Landis allowed Feller to stay with Cleveland. But he made the Indians pay other minor league teams.

Landis was once sued by an owner, Phil Ball of the Browns. Ball disagreed with Landis's ruling on a player. But a judge ruled for Landis. The judge said Landis had "all the attributes of a benevolent but absolute despot." Ball dropped the case.

Landis hoped that large farm systems would not work. But they did. In 1938, he freed 70 players from the Cardinals' farm system. This made headlines. But it didn't stop the growth of modern farm systems. Today, every major league team has several minor league teams to develop talent.

The Baseball Color Line

One of the most debated parts of Landis's time as commissioner is about race. Since 1884, black baseball players were not allowed in organized baseball. No black player played in the major leagues during Landis's time. Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1946, after Landis died.

Some people at the time thought Landis was fair on race issues. But many baseball writers say Landis helped keep black players out of baseball. They say he did little to push owners to integrate. Some authors claim Landis banned major league teams from playing black teams. They feared white teams would lose. However, the Dodgers played black teams as late as 1942.

Landis's actions on race were mixed. In 1938, Yankee player Jake Powell made comments that were seen as racist. Landis suspended Powell for ten days. In 1942, the black Kansas City Monarchs played games against white All-Stars. The Monarchs won all three games. Landis canceled a fourth game. He said the games were drawing too many fans away from major league games. Landis also got involved in a Negro league issue once. He cleared black catcher Josh Gibson of throwing a game.

In 1942, Dodger manager Leo Durocher said there was a secret agreement to keep blacks out of baseball. Landis called him to his office. After the meeting, Durocher said he had been misquoted.

Baseball executive Bill Veeck later claimed he tried to buy the Phillies in 1942. He planned to fill the team with Negro league stars. Veeck wrote that Landis blocked the purchase. Veeck later accused Landis of racism. However, Veeck admitted he had no proof.

In 1943, Landis agreed to let black sportswriter Sam Lacy speak to owners about integration. Instead, actor Paul Robeson spoke. Robeson was a civil rights activist. The owners listened but didn't ask questions.

Many historians believe that Landis was not the only reason for the color line. The team owners also did not want black players in the major leagues. The Baseball Writers' Association of America named its Most Valuable Player Awards after Landis. But in 2020, they removed his name. They said Landis "failed to integrate the game during his tenure."

World Series and All-Star Game Changes

Landis took full control over the World Series. In the 1922 World Series, a game was called due to darkness with a tied score. Landis was blamed. He decided that he would make such decisions in the future. He moved up the start time for World Series games. He also said money from tied games would go to charity. In the 1932 World Series, Landis ordered that tickets for Game One only be sold as part of a package. This meant fans had to buy tickets for all home games. This led to a half-empty stadium. So Landis allowed single game sales for Game Two.

During the 1933 World Series, Landis made a rule. Only he could throw a player out of a World Series game. This happened after a player was ejected by an umpire. The next year, Landis removed Cardinal player Joe Medwick from a game. Medwick was being hit with fruit by angry fans. Landis did this for Medwick's safety. In the 1938 World Series, an umpire was hurt by a wild throw. This led Landis to order six umpires for World Series and All-Star Games.

The All-Star Game started in 1933. Landis strongly supported it. He said it was "a grand show." He never missed an All-Star Game. His last public appearance was at the 1944 All-Star Game.

In 1928, some teams suggested a new rule. The pitcher, usually a weak hitter, would not bat. A tenth player would bat instead. This was an early idea for the "designated hitter" rule. The proposal was later withdrawn. Landis never said how he would have voted.

Landis did not like "night baseball," played under artificial lights. He tried to discourage it. But he did attend the first successful minor league night game in 1930. When major league night baseball began, Landis limited the number of such games. During World War II, more night games were allowed.

World War II, Death, and Legacy

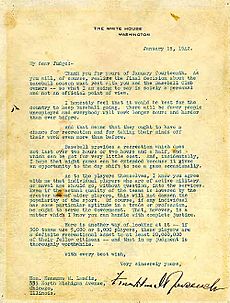

When the United States entered World War II in late 1941, Landis wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He asked about baseball's role during wartime. The President replied, urging Landis to keep baseball going. He said it would be a good break for people working hard for the war. Many major league players joined the military. But Landis kept saying, "We'll play as long as we can put nine men on the field." Teams had to train closer to home during the war. Landis strongly opposed the Axis Powers.

Landis remained in charge of baseball even as he got older. In 1943, he banned Phillies owner William D. Cox from baseball. Cox had bet on his own team. Baseball rules stated that anyone who bets on a game they have a duty to perform in would be banned. Cox had to sell his share of the Phillies.

In October 1944, Landis went to the hospital with a bad cold. He then had a heart attack. He missed the 1944 World Series for the first time. He was still alert and signed the World Series checks for players. His contract was ending in 1946. But on November 17, 1944, owners voted him another seven-year term. However, he died on November 25, five days after his 78th birthday. Landis is buried in Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

Two weeks after he died, Landis was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. American League President Will Harridge said Landis was a "wonderful man." Landis's Hall of Fame plaque says: "His integrity and leadership established baseball in the esteem, respect, and affection of the American people." Many agree that Landis did what he was hired to do: clean up baseball.

See also

In Spanish: Kenesaw Mountain Landis para niños

In Spanish: Kenesaw Mountain Landis para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |