Kenzaburō Ōe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kenzaburō Ōe

|

|

|---|---|

Ōe in 2012

|

|

| Native name |

大江 健三郎

|

| Born | January 31, 1935 Ōse, Ehime, Japan |

| Died | March 3, 2023 (aged 88) Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | Novelist, short-story writer, essayist |

| Alma mater | University of Tokyo |

| Period | 1950–2023 |

| Notable works | A Personal Matter, The Silent Cry |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1994 |

Kenzaburō Ōe (大江 健三郎, Ōe Kenzaburō, 31 January 1935 – 3 March 2023) was a famous Japanese writer. He was a very important person in modern Japanese literature. His books, short stories, and essays were greatly shaped by French and American writing. They explored big ideas like nuclear weapons, nuclear power, not following the crowd (social non-conformism), and existentialism (thinking about the meaning of life). Ōe won the 1994 Nobel Prize in Literature. He received this award for creating "an imagined world where life and myth come together to show a surprising picture of what it means to be human today."

Contents

Life Story

Ōe was born in Ōse (大瀬村, Ōse-mura), a small village in Japan. This village is now part of Uchiko, Ehime Prefecture. He was the third of seven children. His grandmother taught him about art and storytelling.

His grandmother passed away in 1944. Later that same year, his father died during World War II. After this, Ōe's mother became his main teacher. She bought him books like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Ōe said these books had a huge impact on him.

Early School Days

Ōe remembered his elementary school teacher telling them that Emperor Hirohito was a living god. Every morning, the teacher would ask, "What would you do if the emperor told you to die?" Ōe always replied, "I would die, sir. I would cut open my belly and die." But at night, he felt ashamed because he didn't really want to die. After the war, he realized he had been taught lies. This feeling of being betrayed later showed up in his writing.

University and Early Career

Ōe went to high school in Matsuyama. When he was 18, he visited Tokyo for the first time. The next year, he started studying French Literature at Tokyo University. He studied under Professor Kazuo Watanabe, who was an expert on a French writer named François Rabelais. Ōe began publishing his stories in 1957 while he was still a student. His early works were strongly influenced by writers from France and the United States.

In 1959 and 1960, Ōe joined protests against the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. This treaty allowed the United States to keep military bases in Japan. He was part of a group called the "Young Japan Society." Ōe was very disappointed when the protests failed to stop the treaty. This disappointment shaped his future writing.

Family and Challenges

Ōe got married in February 1960 to Yukari. She was the daughter of film director Mansaku Itami. That same year, he met Mao Zedong during a trip to China. He also traveled to Russia and Europe the following year, visiting the famous writer Sartre in Paris.

In 1961, Ōe's short novels Seventeen and The Death of a Political Youth were published. Some extreme right-wing groups were very angry about The Death of a Political Youth. Both Ōe and the magazine received death threats for weeks. The magazine apologized, but Ōe did not. Later, an angry right-winger physically attacked him while he was giving a speech at Tokyo University.

Ōe lived in Tokyo and had three children. His oldest son, Hikari, was born in 1963 with brain damage. Hikari's disability became a very important theme in Ōe's books.

Nobel Prize and Activism

In 1994, Ōe won the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was also offered Japan's Order of Culture, but he refused it. He said he would not accept an award given by the Emperor because he believed "I do not recognize any authority, any value, higher than democracy." He received threats again after this decision.

Ōe was very involved in pacifist (anti-war) and anti-nuclear campaigns. He wrote books about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the people who survived them (called Hibakusha). He met a famous anti-nuclear activist named Noam Chomsky. Chomsky told Ōe how sad he felt when he first heard about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Ōe said he respected Chomsky even more after hearing that story.

After the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, Ōe strongly urged Japan's Prime Minister to stop using nuclear power. He believed Japan had a "moral responsibility" to stop using nuclear energy, just as it had given up war after World War II. He warned that Japan could face another nuclear disaster if it continued to use nuclear power. In 2013, he organized a large protest in Tokyo against nuclear power. Ōe also spoke out against changing Article 9 of Japan's Constitution, which says Japan will never go to war again.

Writing Style and Themes

After winning the Nobel Prize, Ōe explained his writing goal: "I am writing about the dignity of human beings." This means he focused on the value and worth of every person.

His early student works were about his university life. Later, in the late 1950s, he wrote stories like Shiiku (which means "The Catch"). This story was about a Black American soldier who was attacked by Japanese youth. Another book, Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids, focused on children living in a peaceful, natural setting. Ōe saw these child characters as a special kind of "child god" figure.

The books he published between 1961 and 1964 were influenced by existentialism (a philosophy about freedom and responsibility) and picaresque literature (stories about clever, often mischievous characters). These books featured characters who were often outsiders. Their position on the edges of society allowed them to criticize it sharply. Ōe said that Huckleberry Finn was his favorite book, which fits with this period of his writing.

Ōe explained, "I have always wanted to write about our country, our society and feelings about the contemporary scene." He was proud that the Nobel Prize recognized the strength of modern Japanese literature. He hoped the award would encourage other writers.

About His Son Hikari

Ōe often said that his son Hikari greatly influenced his writing career. He tried to give his son a "voice" through his stories. Many of Ōe's books have a character based on Hikari.

In Ōe's 1964 book, A Personal Matter, he wrote about the difficult feelings he had when accepting his brain-damaged son. Hikari is a very important character in many of the books praised by the Nobel committee.

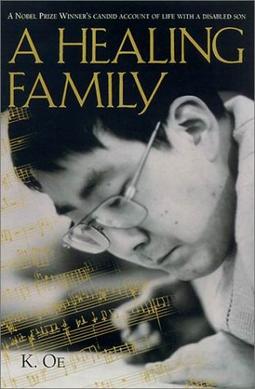

Hikari's life is at the heart of A Healing Family, a book published in 1996 after Ōe won the Nobel Prize. This book celebrates the small successes in Hikari's life.

Hikari also strongly influenced novels like Father, Where are you Going?, Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness, and The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away. These books explore a similar idea: a father with a disabled son tries to understand his own father, who lived a secluded life and died. The father's struggle to understand his own past is compared to his son's difficulty in understanding him.

Later Works (2006–2013)

Ōe didn't write much between 2006 and 2008 because he was involved in a legal case. He later started a new novel with a character based on his own father. His father was a strong supporter of the emperor and drowned in a flood during World War II.

In late 2013, Ōe published a new book called Bannen Yoshikishu, which means In Late Style. This novel is the sixth in a series featuring Kogito Choko, a character often seen as Ōe's literary self. It also continues the "I-novel" style Ōe used since his son was born with a disability in 1963.

In In Late Style, the main character, Choko, loses interest in his own novel after the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami in 2011. Instead, he starts writing about a time of disaster and about getting older himself.

Awards and Recognition

- Akutagawa Prize, 1958

- Shinchosha Literary Prize, 1964

- Tanizaki Prize, 1967

- Noma Prize, 1973

- Yomiuri Prize, 1982

- Jiro Osaragi Prize (from Asahi Shimbun), 1983

- Nobel Prize in Literature, 1994

- Order of Culture, 1994 – refused

- Legion of Honour, 2002

In 2006, the Kenzaburō Ōe Prize was created to support new Japanese novels. Ōe himself chose the winning book. The winner didn't get money, but their novel was translated into other languages.

Selected Works in English

Not all of Kenzaburō Ōe's works have been translated into English or other languages. Many of his books are still only available in Japanese. The few translations often came out much later than the original Japanese versions. His work has also been translated into Chinese, French, and German.

Here are some of his books available in English:

- Shiiku, 1957 - The Catch (published in "The Catch and Other War Stories" in 1981)

- Memushiri Kouchi, 1958 – Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids

- Sevuntiin, 1961 – Seventeen

- Seiteki Ningen 1963 – J

- Kojinteki na taiken, 1964 – A Personal Matter

- Hiroshima noto, 1965 – Hiroshima Notes

- Man'en gannen no futtoboru, 1967 – The Silent Cry

- Warera no kyōki wo ikinobiru michi wo oshieyo, 1969 – Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness (1977)

- Mizukara waga namida wo nuguitamau hi, 1972 – The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away (in Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness)

- Pinchiranna chosho,' 1976 – The Pinch Runner Memorandum

- Atarashii hito yo mezame yo, 1983 – Rouse Up O Young Men of the New Age!

- Jinsei no shinseki, 1989 – An Echo of Heaven

- Shizuka-na seikatsu, 1990 – A Quiet Life

- Kaifuku suru kazoku, 1995 – A Healing Family

- Chugaeri, 1999 – Somersault

- Torikae ko (Chenjiringu), 2000 – The Changeling

- Suishi, 2009 – Death by Water

| Year | Japanese Title | English Title | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | 奇妙な仕事 Kimyou na shigoto |

The Strange Work | His first short story |

| 死者の奢り Shisha no ogori |

Lavish Are The Dead | Short story | |

| 他人の足 Tanin no ashi |

Someone Else's Feet | Short story | |

| 飼育 Shiiku |

Prize Stock / "The Catch" | Short story awarded the Akutagawa prize. Made into a film in 1961 by Nagisa Oshima and in 2011 by the Cambodian director Rithy Panh | |

| 1958 | 見るまえに跳べ Miru mae ni tobe |

Leap before you look | Short story |

| 芽むしり仔撃ち Memushiri kouchi |

Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids | His first novel | |

| 1961 | セヴンティーン Sevuntīn |

Seventeen | Short novel |

| 1963 | 叫び声 Sakebigoe |

Cry | |

| 性的人間 Seiteki ningen |

The *** man (Also known as "J") | Short story | |

| 1964 | 空の怪物アグイー Sora no kaibutsu Aguī |

Aghwee the Sky Monster | Short story |

| 個人的な体験 Kojinteki na taiken |

A Personal Matter | Awarded the Shinchosha Literary Prize | |

| 1965 | 厳粛な綱渡り Genshuku na tsunawatari |

The Solemn Rope-walking | Essay |

| ヒロシマ・ノート Hiroshima nōto |

Hiroshima Notes | Reportage | |

| 1967 | 万延元年のフットボール Man'en gan'nen no futtobōru |

The Silent Cry (published title) Football in the first year of the Manen era(AD 1860) (literal translation) | Novel, awarded the Jun'ichirō Tanizaki prize |

| 1968 | 持続する志 Jizoku suru kokorozashi |

Continuous will | Essay |

| 1969 | われらの狂気を生き延びる道を教えよ Warera no kyōki wo ikinobiru michi wo oshieyo |

Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness | A title is taken from W.H. Auden's Commentary |

| 1970 | 壊れものとしての人間 Kowaremono toshiteno ningen |

A Human Being as a fragile article | Essay |

| 核時代の想像力 Kakujidai no sozouryoku |

Imagination of the Atomic Age | Talk | |

| 沖縄ノート Okinawa nōto |

Okinawa Notes | Reportage | |

| 1972 | 鯨の死滅する日 Kujira no shimetsu suru hi |

The Day Whales Vanish | Essay |

| みずから我が涙をぬぐいたまう日 Mizukara waga namida wo nuguitamau hi |

The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away | ||

| 1973 | 同時代としての戦後 Doujidai toshiteno sengo |

The Post-war Times as Contemporaries | Essay |

| 洪水はわが魂に及び Kōzui wa waga tamashii ni oyobi |

The Flood Invades My Spirit | Awarded the Noma Literary Prize | |

| 1976 | ピンチランナー調書 Pinchi ran'nā chōsho |

The Pinch Runner Memorandum | |

| 1979 | 同時代ゲーム Dojidai gemu |

The Game of Contemporaneity | |

| 1982 | 「雨の木」を聴く女たち Rein tsurī wo kiku on'natachi |

Women Listening to the "Rain Tree" | Awarded the Yomiuri Literary Prize |

| 1983 | 新しい人よ眼ざめよ Atarashii hito yo, mezameyo |

Rouse Up, O Young Men of the New Age! | Awarded the Jiro Osaragi prize |

| 1984 | いかに木を殺すか Ikani ki wo korosu ka |

How Do We Kill the Tree? | |

| 1985 | 河馬に嚙まれる Kaba ni kamareru |

Bitten by the Hippopotamus | Awarded the Yasunari Kawabata Literary Prize |

| 1986 | M/Tと森のフシギの物語 M/T to mori no fushigi no monogatari |

M/T and the Narrative About the Marvels of the Forest | |

| 1987 | 懐かしい年への手紙 Natsukashī tosi eno tegami |

Letters for Nostalgic Years | |

| 1988 | 「最後の小説」 'Saigo no syousetu' |

'The Last Novel' | Essay |

| 新しい文学のために Atarashii bungaku no tame ni |

For the New Literature | Essay | |

| キルプの軍団 Kirupu no gundan |

The Army of Quilp | ||

| 1989 | 人生の親戚 Jinsei no shinseki |

An Echo of Heaven(published title)Relatives of life (literal translation) | Awarded the Sei Ito Literary Prize |

| 1990 | 治療塔 Chiryou tou |

The Tower of Treatment | |

| 静かな生活 Shizuka na seikatsu |

A Quiet Life | ||

| 1991 | 治療塔惑星 Chiryou tou wakusei |

The Tower of Treatment and the Planet | |

| 1992 | 僕が本当に若かった頃 Boku ga hontou ni wakakatta koro |

The Time that I Was Really Young | |

| 1993 | 「救い主」が殴られるまで 'Sukuinushi' ga nagurareru made |

Until the Savior Gets Socked | 燃えあがる緑の木 第一部 Moeagaru midori no ki dai ichi bu The Flaming Green Tree Trilogy I |

| 1994 | 揺れ動く (ヴァシレーション) Yureugoku (Vashirēshon) |

Vacillating | 燃えあがる緑の木 第二部 Moeagaru midori no ki dai ni bu The Flaming Green Tree Trilogy II |

| 1995 | 大いなる日に Ōinaru hi ni |

On the Great Day | 燃えあがる緑の木 第三部 Moeagaru midori no ki dai san bu The Flaming Green Tree Trilogy III |

| 曖昧な日本の私 Aimai na Nihon no watashi |

Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself: The Nobel Prize Speech and Other Lectures | Talk | |

| 恢復する家族 Kaifukusuru kazoku |

A Healing Family | Essay with Yukari Oe | |

| 1999 | 宙返り Chūgaeri |

Somersault | |

| 2000 | 取り替え子 (チェンジリング) Torikae ko (Chenjiringu) |

The Changeling | |

| 2001 | 「自分の木」の下で 'Jibun no ki' no shita de |

Under the "Tree of Mine" | Essay with Yukari Oe |

| 2002 | 憂い顔の童子 Ureigao no dōji |

The Infant with a Melancholic Face | |

| 2003 | 「新しい人」の方へ 'Atarashii hito' no hou he |

Toward the "New Man" | Essay with Yukari Oe |

| 二百年の子供 Nihyaku nen no kodomo |

The Children of 200 Years | ||

| 2005 | さようなら、私の本よ! Sayōnara, watashi no hon yo! |

Farewell, My Books! | |

| 2007 | 臈たしアナベル・リイ 総毛立ちつ身まかりつ Routashi Anaberu rī souke dachitu mimakaritu |

The Beautiful Annabel Lee was Chilled and Killed | |

| 2009 | 水死 sui shi |

Death by Water | |

| 2013 | 晩年様式集(イン・レイト・スタイル) Bannen Youshiki shū (In Reito Sutairu) |

In Late Style |

See also

In Spanish: Kenzaburō Ōe para niños

In Spanish: Kenzaburō Ōe para niños

- List of Japanese Nobel laureates

- List of Nobel laureates affiliated with the University of Tokyo

- Anti-nuclear power movement in Japan

- Relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma