Kultarr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kultarr |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Dasyuromorphia |

| Family: | Dasyuridae |

| Subfamily: | Sminthopsinae |

| Tribe: | Sminthopsini |

| Genus: | Antechinomys Krefft, 1867 |

| Species: |

A. laniger

|

| Binomial name | |

| Antechinomys laniger (Gould, 1856)

|

|

|

|

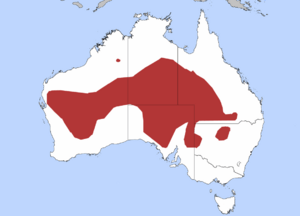

| Distribution of the kultarr | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The kultarr (Antechinomys laniger), also called the "jerboa-marsupial," is a small animal that eats insects. It is active at night and lives in the dry, inner parts of Australia. Kultarrs live in places like rocky deserts, areas with shrubs and trees, grasslands, and open plains. They have special ways to deal with Australia's tough, dry weather. For example, they can go into a deep sleep called torpor, which is like a short hibernation. This helps them save energy. Since people from Europe settled in Australia, the number of kultarrs has gone down. This is because of changes in how the land is managed and new animals that hunt them.

Contents

Description

The kultarr is a small meat-eating marsupial from the Dasyuridae family. It has unique body features. Kultarrs are nocturnal, meaning they are active at night. They hunt many different insects and other small creatures, like spiders, crickets, and cockroaches. During the day, they hide in burrows, hollow logs, under grass, at the bottom of plants, or in cracks in the ground.

Male kultarrs weigh between 17 and 30 grams and are 80–100 mm long. Females are a bit smaller, weighing 14–29 grams and measuring 70–95 mm. They are brown or sandy-colored on top and white underneath. The kultarr has a long tail with a special dark, brush-like tip. Its nose is very pointy, and its eyes and ears are quite large. There are dark rings around its eyes.

Kultarrs have long back legs with four toes, similar to kangaroos and wallabys. These legs are made for hopping or moving on two feet. This helps them escape from predators and catch insects. Kultarrs have been seen moving as fast as 13.8 km/h in open areas.

Taxonomy (How Kultarrs Are Classified)

The kultarr is the only animal in its group, called Antechinomys, which belongs to the Dasyuridae family. The first kultarr was found by Sir Thomas Mitchell in New South Wales. Later, in 1856, John Gould gave it the name Phascogale lanigera.

In 1867, Krefft put the kultarr into its own group, Antechinomys. In 1888, it was officially named Antechinomys laniger.

There are two types of kultarrs, called subspecies: A. laniger laniger and A. laniger spenceri. They have small differences in their looks and live in different places. A. laniger laniger lives in eastern Australia, while A. laniger spenceri is found in western and central Australia. A. laniger spenceri is usually lighter in color and heavier than A. laniger laniger.

Distribution (Where Kultarrs Live)

Kultarrs live across a huge part of dry and semi-dry Australia. However, their numbers have gone down in some areas, and they are now uncommon. Their populations can also change with the seasons. Kultarrs have disappeared from Victoria and southern New South Wales. They are also gone from parts of south-east South Australia, north Queensland, and western Queensland.

The kultarr populations in the Northern Territory and Western Australia seem to be steady. Kultarrs around Cobar in western New South Wales are still there, and these groups are important for saving the species. Kultarrs were seen in 2015 at Nombinnie Nature Reserve in Central Western NSW. This was a big deal because they hadn't been seen there for over 20 years.

Ecology and Behavior

Life Cycle and Reproduction

We don't know how long kultarrs live in the wild, but in zoos, they can live up to 5 years. Kultarrs in different parts of Australia have different breeding seasons. In eastern Australia, breeding starts in the second half of the year. In western Australia, it begins a little later. Males can have babies at 9–10 months old, and females at 11–12 months.

Female kultarrs can have several breeding cycles in one season. The kultarr has a crescent-shaped pouch with small skin folds and six to eight teats (nipples). The young stay in the pouch for up to 20 days. After that, they hold onto their mother's back while she hunts, or they are left in the burrow.

The two subspecies have different numbers of teats. A. laniger laniger has eight, and A. laniger spenceri has six. This can help tell them apart. Breeding and raising kultarrs in zoos can be difficult.

Home Range and Movement

Kultarrs move between different places throughout the year. This means the number of kultarrs in a local area can change with the seasons. Their numbers might even go down after good rain, as kultarrs prefer drier times.

How far kultarrs move and their home range can vary. Males have been recorded moving up to 1,700 meters per night, and females up to 400 meters per night. Kultarrs travel through different types of habitats to find food, including areas with plants and open, bare ground.

Diet

The kultarr mainly eats insects. Its diet includes spiders, cockroaches, crickets, and beetles. Kultarrs are also known to hunt and eat other small marsupials from the Dasyuridae family.

Habitat

Kultarrs live in many different habitats, but they prefer areas with few plants. These habitats include claypans, rocky plains, stony deserts, savannas, and grasslands with hummock grass (like Triodia). They also live in woodlands and shrublands.

Kultarrs in western Australia prefer stony, granite plains with Acacia, Eremophila, and Cassia plants. Kultarrs in eastern Australia prefer claypans with few plants in acacia woodlands.

Torpor as an Adaptation

The kultarr has a fast metabolism, which means its body uses a lot of energy. To save energy, the kultarr goes into a state called torpor. During torpor, its body temperature drops to about 11 °C. This slows down its metabolism by 30%, saving energy and reducing water loss. Torpor usually happens in the evening or early morning and can last from 2 to 16 hours.

Animals that can go into torpor are called heterothermic endotherms. Other marsupials in dry Australia also use torpor. It's a way for them to deal with limited food and water.

One benefit of torpor is that it can help kultarrs live longer. This is helpful in the harsh, dry environment because it allows populations to recover after bad weather events like flooding or drought. Torpor is also used during the breeding season to help ensure that babies can be born even when conditions are not good.

Threats to Survival

Habitat Degradation

Since European settlement, changes in how land is managed have caused many native animals in dry Australia to disappear. Habitats are damaged by too much grazing from introduced animals like rabbits, sheep, and cattle. Cattle can stomp on and destroy plants, damage the soil, and reduce deep cracks in the ground. These cracks are important places for kultarrs to nest and hide.

Predation by Cats and Foxes

Kultarrs are threatened by introduced predators like feral cats and red foxes. When there is good rainfall in dry areas, the number of predators can increase. This leads to more kultarrs being hunted. Native animals like owls and snakes also hunt kultarrs. However, cats are different from native predators because they hunt for fun and will keep hunting even when there are not many kultarrs left. Cats on cattle farms have also been seen hunting kultarrs.

Flooding

Kultarr populations can drop a lot because of flooding. Floods can cause kultarrs to drown or their burrows to fill with water. If kultarr groups are isolated, it's harder for them to recover after a flood. Severe flooding also destroys kultarr habitats.

Fire

Before European settlement, Indigenous people used controlled burning to manage the land. Since this practice stopped, and there is less patch-mosaic burning in dry Australia, large wildfires have become more severe. These fires destroy important habitats and hiding places for the kultarr, such as tree hollows, fallen logs, hummock grasses (like Triodia), shrubs, and leaf litter.

Insecticides Used to Control Locusts

Insecticides used to control Australian plague locusts might be causing the death of some marsupials, including kultarrs, through secondary poisoning. Kultarrs are especially at risk because they eat many insects, have a fast metabolism, and are small. When locusts are affected by insecticide, kultarrs can easily catch and eat many of them, making them vulnerable to poisoning.

Conservation and Management

Current Status

The kultarr is listed as endangered in New South Wales under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995. It is listed as near threatened in the Northern Territory under the Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2000.

In Queensland, it is listed as least concern under the Nature Conservation Act 1992. The kultarr is not listed in South Australia, Victoria, or Western Australia. It is also listed as least concern on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ‘red list’ of threatened species.

Targeted Conservation Programs

The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service has created a detailed plan to help the kultarr recover, as part of their ‘saving our species’ program. This plan aims to:

- Find out where kultarrs live and what kind of habitat they need.

- Identify specific threats to the species.

- Put in place direct ways to manage and reduce these threats.

- Educate the public to raise awareness about the kultarr.

Currently, there are no plans to reintroduce kultarrs into the wild.

Some direct ways to help the kultarr include:

- Programs to control foxes, rabbits, and feral cats.

- Keeping up patch-mosaic burning in the landscape.

- Reducing the number of livestock on properties and keeping cattle out of important kultarr habitats.

- Keeping understory plants, groundcover, logs, and leaf litter.

- Reporting any new sightings of the species.

See also

In Spanish: Kultarr o ratón marsupial lanudo para niños

In Spanish: Kultarr o ratón marsupial lanudo para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |