Lady Hester Stanhope facts for kids

Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope (born March 12, 1776 – died June 23, 1839) was a brave British noblewoman, adventurer, and expert in ancient history. She was one of the most famous travelers of her time. Her archaeological dig in Ashkelon in 1815 is seen as one of the first to use modern methods. She was also one of the first archaeologists to use old documents to help her find things. Her exciting letters and stories made her well-known as an explorer.

Contents

Early Life and Travels

Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope was the oldest child of Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope, and Lady Hester Pitt. She was born at her father's home, Chevening. She lived there until 1800, when she moved to live with her grandmother.

In 1803, she moved in with her uncle, William Pitt the Younger. He was the British prime minister and needed help managing his home and hosting important guests. Lady Hester became known for her beauty and great conversation skills. When her uncle was not prime minister, she worked as his private secretary. After Pitt's death in 1806, she received a yearly payment from Britain. After living in London and Wales, she left Great Britain for good in February 1810. A sad event in her life is said to have made her decide to go on a long sea journey.

Her group included her doctor, Charles Lewis Meryon, her maid, Anne Fry, and an adventurer named Michael Bruce. When they arrived in Athens, the famous poet Lord Byron reportedly swam out to greet her. Byron later said she was "that dangerous thing, a female wit," meaning she was very clever and sharp. From Athens, Lady Hester's group traveled to Constantinople (now Istanbul), which was the capital of the Ottoman Empire. They planned to go to Cairo, Egypt.

Adventures in the Middle East

On the way to Cairo, Lady Hester's ship was caught in a storm and wrecked near Rhodes. They lost all their belongings. The group borrowed Turkish clothes. Lady Hester chose to dress like a Turkish man, wearing a robe, turban, and slippers. She refused to wear a veil. When a British ship took them to Cairo, she continued to wear her unusual clothes. She bought a purple velvet robe, embroidered trousers, a waistcoat, a jacket, a saddle, and a sword. She even wore this outfit to meet the local ruler.

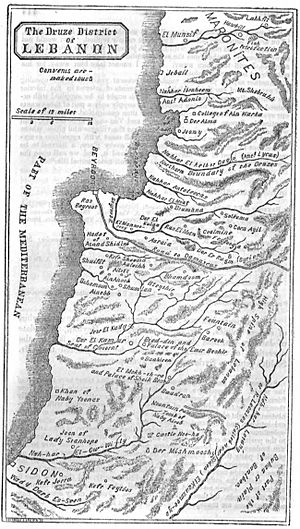

From Cairo, she continued her travels in the Middle East. Over two years, she visited many places, including Gibraltar, Malta, Athens, Constantinople, Rhodes, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. She still refused to wear a veil, even in Damascus. In Jerusalem, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was even cleared of visitors and opened just for her.

Lady Hester heard from fortune-tellers that she would marry a new leader. She tried to meet Ibn Saud, a powerful Arab chief. She decided to visit the ancient city of Palmyra, even though the journey crossed a desert with possibly unfriendly Bedouin groups. She dressed like a Bedouin and took a long line of 22 camels to carry her bags. The local leader, Emir Mahannah el Fadel, welcomed her, and she became known as "Queen Hester."

First Modern Dig in Ashkelon

Lady Hester found an old Italian document that said a great treasure was hidden under the ruins of a mosque in the port city of Ashkelon. This city had been in ruins for 600 years. In 1815, using this document, she traveled to the ruins of Ashkelon on the Mediterranean coast, north of Gaza. She convinced the Ottoman government to let her dig there. The governor of Jaffa was ordered to go with her. This was the first archaeological excavation (dig) in Palestine.

Lady Stanhope and her doctor, Meryon, carefully studied the history of the buildings in Ashkelon. They did this even before modern archaeological methods were well known. Meryon noted that the site had likely been a temple, then a church, and then a mosque. This careful way of looking at layers of history was very new for the time.

Even though she didn't find the treasure of three million gold coins, her team dug up a seven-foot-tall marble statue without a head. Lady Hester then ordered the statue to be broken into "a thousand pieces" and thrown into the sea. This might seem strange, but she did it to show the Ottoman government that she was not trying to steal valuable old items for Europe. Many other Europeans were taking ancient artifacts from the region at that time. She wanted to show her good intentions and that she was looking for treasures for them.

This dig by Lady Hester helped open the way for future archaeological work and tourism to the site.

Life Among the Arabs

Lady Hester settled near Sidon, a town on the Mediterranean coast in what is now Lebanon. She first lived in an old monastery and then moved to another. Her companion, Miss Williams, and her doctor, Charles Meryon, stayed with her for some time. Miss Williams died in 1828, and Meryon left in 1831, only returning for a short visit later. When Meryon left, Lady Hester moved to a faraway, abandoned monastery at Joun, a village near Sidon. She lived there until she died. Her home, called Dahr El Sitt by the villagers, was on top of a hill. Meryon said she liked the house because she could see people coming and going from all directions.

At first, a local leader named Bashir Shihab II welcomed her. But over the years, she gave shelter to many people who were escaping conflicts between different groups. This made the leader unhappy with her. In her new home, she became very powerful in the areas around her. She was almost like the ruler of the region. Her influence over the local people was so strong that when Ibrahim Pasha planned to invade Syria in 1832, he asked her to stay neutral. She kept her power because of her strong personality and because people believed she could predict the future. She wrote letters to important people and welcomed curious visitors who traveled far to see her.

Lady Hester found herself in a lot of debt. She used her pension from England to pay off people she owed money to in Syria. From the mid-1830s, she became more and more private. Her servants began to steal her belongings because she was less able to manage her household. Lady Stanhope might have been very sad or perhaps she was getting older and confused. In her last years, she would only see visitors after dark, and even then, she would only let them see her hands and face. She wore a turban over her shaved head. She died peacefully in her sleep in 1839.

About Her Life

After her death, her doctor, Charles Meryon, published books about her life. These included Memoirs of the Lady Hester Stanhope as related by herself in Conversations with her Physician (1846) and Travels of Lady Hester Stanhope, forming the Completion of her Memoirs narrated by her Physician (1847).

In Books and Movies

Lady Hester Stanhope has been mentioned in many books and movies:

- 1838: A poem called "Djouni: the Residence of Lady Hester Stanhope" by Letitia Landon was published.

- 1844: The book Eothen by Alexander Kinglake has a chapter about Lady Hester Stanhope.

- 1876: George Eliot's novel Daniel Deronda calls her "Queen of the East."

- 1876: Louisa May Alcott's novel Rose in Bloom mentions her.

- 1882: William Henry Davenport Adams's book Celebrated Women Travellers Of The Nineteenth Century has a chapter about her.

- 1922: Molly Bloom remembers Hester Stanhope's travels in Ulysses by James Joyce.

- 1924: Pierre Benoit wrote about her in "Lebanon's Lady of the Manor."

- 1958: She is mentioned in Georgette Heyer's novel Venetia.

- 1961: In the novel Herzog by Saul Bellow, her writing style is compared to a character's.

- 1967: Lady Hester Stanhope was the inspiration for Great-Aunt Harriet in Mary Stewart's novel The Gabriel Hounds.

- 1986: The character Lady Ashley in the TV movie Harem was loosely based on her.

- 1995: Queen of the East, a TV movie about Stanhope, starred Jennifer Saunders.

- 2014: Brett Josef Grubisic's novel This Location of Unknown Possibilities talks about a TV show attempt about her travels.

See also

In Spanish: Hester Stanhope para niños

In Spanish: Hester Stanhope para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |