Golden lion tamarin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Golden lion tamarin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male at Copenhagen Zoo, Copenhagen, Denmark | |

|

|

| Female at the Bronx Zoo, New York, United States | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Leontopithecus

|

| Species: |

rosalia

|

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

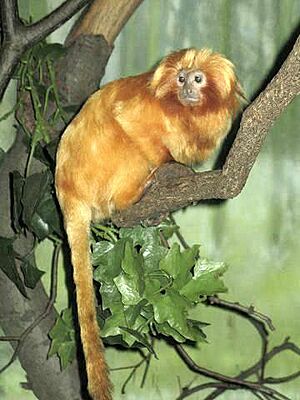

The golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia) is a small, bright orange monkey. It is also sometimes called the golden lion marmoset. These monkeys are a type of New World monkey, meaning they live in the Americas. They belong to a family of small monkeys called callitrichines.

Golden lion tamarins are found only in the Atlantic coastal forests of Brazil. This makes them an endemic species. Their home is entirely within the state of Rio de Janeiro. A count in 2022/2023 estimated there were about 4,800 of these tamarins living in the wild. There are also about 490 golden lion tamarins living in zoos around the world. This species is currently considered endangered.

Contents

Physical Characteristics of Golden Lion Tamarins

The golden lion tamarin gets its name from its bright reddish-orange fur. It also has long hair around its face and ears, which looks like a lion's mane. Its face is dark and does not have hair. The bright orange color of their fur does not come from carotenoids, which are common natural pigments.

These tamarins are the largest of the callitrichine monkeys. They are usually about 26.1 centimeters (10.3 inches) long. They weigh around 620 grams (1.4 pounds). Males and females are almost the same size. Unlike most monkeys, golden lion tamarins have claw-like nails instead of flat nails. However, they do have a flat nail on their big toe. These claws help them cling to the sides of tree trunks. They can also move on all fours along small branches, similar to how squirrels move.

Golden Lion Tamarin Habitat

The golden lion tamarin lives in a small area today. Much of its original home in Brazil's Rio de Janeiro state has been lost due to deforestation. Now, these monkeys live in small pieces of forest. These areas include the Poço das Antas Biological Reserve and the União Biological Reserve. They also live in other protected areas and on private lands.

Most of their habitat is dense evergreen or seasonal forests. Some tamarins near the coast live in a sandy forest type called "arboreal restinga." Golden lion tamarins usually live in low-lying forests, up to 150 or 300 meters (490 to 980 feet) above sea level. However, some groups have been found at higher elevations, even above 700 meters (2,300 feet).

Population Growth and Conservation Efforts

In the 1960s and 1970s, there were only an estimated 100 to 600 golden lion tamarins in the wild. The first full count in 1990-1992 found about 560 wild individuals. There were also about 100 more from a reintroduction program.

Since then, conservation efforts have helped the population grow a lot. These efforts include bringing zoo-born animals back to the wild. They also involve moving wild tamarins from small, risky forest areas to safer ones. Reforestation, especially connecting separate habitats, has also helped. Local communities have also joined in conservation programs. The most recent count in 2022/2023 estimated about 4,800 golden lion tamarins in their main living areas.

Golden Lion Tamarin Behavior and Ecology

Golden lion tamarins are active for up to 12 hours each day. They use a different sleeping spot every night. By moving their sleeping nests often, they leave less scent behind. This makes it harder for predators to find them.

Their day starts with traveling and eating fruits. As the afternoon comes, they look for insects more. By late afternoon, they move to their night dens. Tamarin groups sleep in hollow tree cavities, thick vines, or epiphytes. They prefer spots that are 11 to 15 meters (36 to 49 feet) off the ground. Tamarins are active earlier and go to bed later during warmer, wetter times of the year. This is because the days are longer. In drier times, they spend more time looking for insects because food is scarcer.

Foraging and Diet

Golden lion tamarins are known for finding food by using their hands to search under tree bark and in bromeliads. They spread their foraging sites across their large home ranges. These ranges average 123 hectares (304 acres). This helps them find enough food over long periods. Even if two groups' home ranges overlap, they rarely interact. This is because their foraging sites are spread out. They spend half their time in only about 11% of their home range.

The golden lion tamarin eats many different things. Their diet includes fruits, flowers, nectar, bird eggs, insects, and small animals. They use small areas called microhabitats for finding food. These include bromeliads, palm crowns, tree bark, and rotten logs. The golden lion tamarin uses its long fingers to pull prey from cracks and under leaves. This behavior is called micromanipulation. Insects make up 10–15% of their diet. Most of the rest is small, sweet fruits. During the rainy season, they mainly eat fruit. In drier times, they eat more nectar and gums. They also eat more small animals when insects are harder to find.

Social Structure

Golden lion tamarins are social animals. Their groups usually have 2 to 8 members. These groups often have one breeding male and one breeding female. Sometimes, there might be 2–3 males and one female, or the other way around. Other members include younger tamarins, who are usually the offspring of the adults.

If there is more than one breeding adult, one is usually dominant. This is kept through aggressive behavior. Both males and females can leave their birth group around age four. Females might take over as the breeding adult if their mother dies. This can cause the breeding male (who is likely her father) to leave. This does not happen with males and their fathers. Males who leave their group may join other males until they find a new group to join. Most new members joining groups are males. A male might join a group if the current male dies or disappears. Males can also force out resident males, often two brothers working together. If this happens, only one of the new males will breed. Golden lion tamarins are very territorial. Groups will protect their home range and food sources from other groups.

Tamarins use different sounds to communicate. They make "whine" and "peep" calls for alarms or to show alliances. "Clucks" are used during foraging or when they are aggressive towards other tamarins or predators. "Trills" are used to talk over long distances and show where an individual is. "Rasps" or "screeches" are usually for playful behavior. Tamarins also use chemicals to mark their territory. Breeding males and females mark their territory the most. Dominant males use scent marking to show their status. This can even stop other males from breeding.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Golden lion tamarins mostly have one male and one female mating (monogamous). If there are two adult males in a group, only one will mate with the female. Sometimes, a male might mate with two females, usually a mother and daughter. Breeding depends on rainfall. Mating is highest at the end of the rainy season, from late March to mid-June. Births happen most during the September–February rains.

Females can have babies when they are 15–20 months old. However, they usually don't reproduce until they are 30 months old. Only the dominant female in a group can reproduce. She will stop other females in the group from having babies. Males can reach puberty around 28 months. Tamarins are pregnant for four months.

Golden lion tamarin groups help each other raise the babies. This is because mothers often give birth to twins, and sometimes triplets or quadruplets. A mother cannot care for all her babies alone. She needs help from other group members. Younger members might miss chances to breed, but they gain experience in raising their younger siblings. For their first 4 weeks, babies rely completely on their mother for feeding and carrying. By week five, babies spend less time on their mother's back and start exploring. Young tamarins become juveniles at 17 weeks and will socialize with other group members. They reach the sub-adult phase at 14 months, when they start showing adult behaviors.

Ecosystem Role

Golden lion tamarins have a special relationship with 96 plant species in the Atlantic Forest. This is a mutualistic interaction. The tamarins help spread seeds, and the plants provide food. Tamarins visit plants with lots of resources again and again. They move around their territory, so seeds are spread far from the parent plant. This is good for germination (when seeds sprout). Their seed spreading is important for the forest to grow back. It also helps with the genetic variety and survival of endangered plant species.

Threats from Predators

Studies show that more predators have caused a big drop in tamarin numbers. Predators attack golden lion tamarins at their sleeping sites. These sites are mainly tree holes (about 63.6% of the time). Predators make these holes bigger to attack the tamarins, sometimes wiping out an entire family. Tamarins prefer tree holes in living trees next to other large trees with a small amount of canopy cover. These spots offer protection and easy access to food. Most tree holes are lower to the ground, making them easier to enter. Tree holes in living trees are also drier, warmer, and have fewer insects, which means fewer diseases. Less canopy cover helps tamarins spot predators faster. Being surrounded by other large trees gives them escape routes.

Due to habitat loss, there are fewer trees that can support whole groups. Some tamarins have to use bamboo (17.5%), vine tangles (9.6%), and bromeliads (4.7%) as sleeping sites. This makes them more open to predators. Golden lion tamarins use different den sites but do not change them often. They are more likely to reuse safe sites. However, predators can learn where these sites are. Tamarins also scent mark their den holes. This helps them find their way back in the afternoon when predators are most active. But too much scent also helps predators find them. Also, more deforestation means less habitat, giving predators easier access to their prey. This has led to a decline in the golden lion tamarin population.

Golden Lion Tamarin Conservation Efforts

Threats to the golden lion tamarin include illegal logging, poaching, mining, urbanization, deforestation, pet trading, infrastructure development, and new alien species. In 1969, only about 150 individuals were left in the Atlantic Forest.

In 1975, the golden lion tamarin was listed under Appendix I of CITES. This means it is an animal threatened with extinction that might be affected by trade. The IUCN listed the species as Endangered in 1982. By 1984, the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C. and the World Wide Fund for Nature, through the Golden Lion Tamarin Association, started a program to reintroduce tamarins from zoos.

Despite the program's success, the IUCN changed the species' status to Critically Endangered in 1996. By 2003, a new population was successfully established at União Biological Reserve. This allowed the species to be downgraded back to endangered. However, the IUCN warns that extreme habitat loss means the wild population cannot expand much more. Several conservation programs have been started to stop the tamarin's sharp decline. The goal is to make the wild population stronger and keep a safe population in zoos worldwide. Reintroduced animals have survived well, but destruction of unprotected habitat continues.

Reintroduction Programs

In the early 1980s, the Smithsonian National Zoological Park and the Rio de Janeiro Primate Center began a program. They wanted to reintroduce golden lion tamarins born in zoos to help the wild population. At that time, there were thought to be no more than 600 wild individuals. From 1984 to 2000, 146 zoo-born and seven wild-born tamarins (who had been taken illegally) were released into the wild. These animals came from 43 different zoos and research centers. None of the release sites were thought to have wild golden lion tamarins at the time.

All zoo-born tamarins had health checks before release. Those from Europe or the United States were kept separate for 30 days. All were allowed to get used to outdoor cages at the release sites for at least 24 hours. The animals were watched closely for at least three months after release. Most were given extra food and artificial shelters for several months. If they got lost, they were caught and returned to the release site. This strong support after release helped them survive better.

Over time, some of the reintroduced tamarins or their offspring were moved to other private locations. Forest recovery on private lands also allowed tamarins to spread to more ranches and farms. As of 2022, 22 of these farms and ranches with golden lion tamarins were official private nature reserves. The most recent count in 2022/2023 estimated that 2,256 surviving descendants of reintroduced tamarins were living in the wild. This is almost half (46%) of the total estimated population in their main habitat area.

Translocation Efforts

During a survey in 1990-1992, some golden lion tamarin groups were found in very small or threatened forest areas. Between 1994 and 1997, 43 individuals from these areas were rescued. They were moved to what would become the União Biological Reserve in 1998. This reserve was in the species' historic range but had no tamarins at the time. The main goals of moving these tamarins were to save those in danger and to add genetic diversity to the more protected population.

The population at the União reserve has grown a lot since these moves. By December 2000, the population had grown to 120. By 2006, it was more than 220 in 30 family groups. The most recent count in 2022-2023 estimated that there were 473 descendants of the original moved golden lion tamarins. This makes up 10% of the total estimated population of 4,869 in their main habitat area.

Effects of Habitat Loss

Golden lion tamarins are native to Brazil's Atlantic Forest. Their original home stretched from the southern part of Rio de Janeiro state to the southern part of Espirito Santo state. However, deforestation for business, predators, and catching tamarins for the pet trade have limited their population. Now, they live in only about five areas across Rio de Janeiro. Most of the population is found in the Poco das Antas Biological Reserve.

Because of deforestation and the breaking up of the Atlantic forest, their home ranges have shrunk. The forest now consists of thousands of small pieces, only 8% of its original size. This directly affects where they can find food and how many resources are available to them.

How Habitat Loss Affects Young Tamarins

The type of trees in their habitat also affects how tamarins behave and interact. For example, it greatly impacts how young golden lion tamarins play. Play between different ages and species is important for their social, thinking, and movement skills. It also helps them learn how to deal with competition and predators. How they play often shows how they will act when facing danger.

Social play happens more on large branches (over 10 cm wide) and in vine tangles (4 meters above ground). These areas are considered safe because they are less open to predators. Playing in dangerous areas like canopy branches or the forest floor makes them more vulnerable. So, deforestation reduces the safe places for young tamarins to play. This means less play, and less development of important survival skills. If they do play in dangerous areas, they are more exposed to predators, which leads to fewer tamarins. This is similar to how predators affect their sleeping sites. Being exposed to predators affects not only young tamarins but also adults. Play often happens in the center of the group to protect the young.

Increased Inbreeding

Deforestation and habitat breaking up also lead to unstable populations. This increases the chance of inbreeding, which is when closely related animals breed. Inbreeding can cause inbreeding depression, meaning offspring are less healthy and less likely to survive. This leads to a population decline. The problem is that golden lion tamarins live in more and more isolated forest pieces. Inbreeding results in low genetic diversity. Inbred offspring have a lower chance of survival than those not inbred.

Habitat fragmentation also means tamarins are less likely to move to new areas. This reduces breeding with individuals from other groups. So, inbreeding depression is seen in these populations. With delayed breeding, the shrinking and lack of territory force golden lion tamarins to move to find needed resources and suitable areas. However, moving is risky and takes a lot of energy that could be used for reproduction instead.

Yellow Fever Epidemic

A yellow fever outbreak in southeastern Brazil from 2016-2018 greatly affected the golden lion tamarin population. It reduced their numbers by 32% to about 2,516 individuals. The tamarin population faced more losses in larger forest areas. These areas had fewer edges and were more connected. These conditions could help the mosquitoes that spread yellow fever to be present and spread the disease.

The outbreak was especially bad in the Poço das Antas Biological Reserve. The population there dropped from around 400 tamarins to only 32. This decline was partly blamed on human activities, like the expansion of the BR-101 highway. This highway brings a constant flow of traffic into the area. Researchers noted that the disease spread quickly across Brazil because infected people moved around.

In response, Brazilian scientists created a special yellow fever vaccine for golden lion tamarins. The vaccine program started in 2021. By February 2023, over 300 tamarins had been vaccinated with no bad effects reported. The vaccine works well, with 90-95% of retested monkeys showing immunity. By February 2023, the yellow fever outbreak had ended, and the tamarin population had become stable again.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tamarino león dorado para niños

In Spanish: Tamarino león dorado para niños